Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 41 nº 1 - Jan. /Feb. of 2008

Vol. 41 nº 1 - Jan. /Feb. of 2008

|

WHICH IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

|

|

Which is your diagnosis? |

|

|

Autho(rs): Daniella Ferraro Fernandes Costa, Luiz Tenório de Brito Siqueira, Marcelo Bordalo-Rodrigues |

|

|

IMD, Resident at Instituto de Radiologia do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (InRad/HC-FMUSP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil

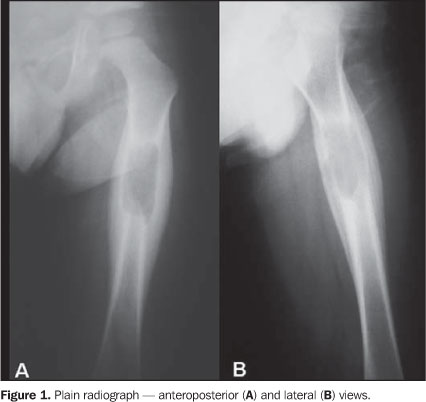

Male, three-year-old patient complaining of pain in the left lower limb for one month, without any other associated symptom. Images description Figure 1. Lytic lesion with partially well-defined margins, centrally located in the middle/proximal third of the femoral diaphysis. Lamellar periosteal reaction ("onion peel" pattern) is observed.

Figure 2. Diaphyseal lesion presenting hyposignal on T1-weighted sequence, and hypersignal on T2-weighted sequence with fat saturation. Proximal, medullary hypersignal adjacent to the lesion is observed. Also, lamellar periosteal reaction is observed, besides hypersignal in soft tissues surrounding the lesion, corresponding to edema.

Figure 3. Lesion with hyposignal on T1-weighted, and hypersignal on T2-weighted sequences, demonstrating erosion of the posterior cortical bone. After paramagnetic contrast agent injection, an intense enhancement of the lesion, periosteum and soft tissues is demonstrated. Diagnosis: Langerhans' cell histiocytosis.

COMMENTS Langerhans' cell histiocytosis covers a spectrum of diseases characterized by the idiopathic proliferation of atypical histiocytes and formation of granulomas resulting in focal or systemic alterations(1). Eosinophilic granulomatosis, also known as a localized presentation of the disease, presents an involvement restricted to bones or lungs, corresponding to 70% of cases of Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. It is the most benign expression of the disease, besides being the most favorable in terms of prognosis(2,3). In these cases, Langerhans' cell histiocytosis may affect any bone, although the incidence is higher in flat bones. More than 50% of eosinophilic granulomas present like a lytic lesion with a destructive component. Although less frequently, periosteal reaction and permeative pattern may be present(4–6). The skull is the most affected region, with the calvaria, particularly in the parietal region, being more frequently affected than the skull base. The mandible, ribs and pelvis are other frequent sites of involvement(5). Approximately 25%–35% of monostotic lesions affect long bones, especially femur, humerus and tibia, most frequently in the diaphyseal region (58%), followed by the metaphyseal region (28%), metadiaphyseal (12%), and rarely the epiphyseal region (2%)(4,5,7). The majority of patients are asymptomatic, although pain, edema and, less frequently, a pathological fracture may occur in the site of the lesion(4). Fever and leukocytosis also may be present. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis may affect patients at any age, although there is a prevalence of cases in persons less than 15 years old, with a slight male preponderance(8). Two other clinical syndromes are part of the Langerhans' cell histiocytosis spectrum: Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, a chronic and recurrent presentation corresponding to 15%–20% of cases, affects multiple bones (predominantly the skull) and the endothelial-reticular system, and is most frequently found in male children between one and five years of age. The acute, fulminant presentation of Langerhans' cell histiocytosis, also known as Letterer-Siwe disease, corresponds to 10% of cases and occurs predominantly in children younger than two years of age without sex predilection. There is a systemic bone and endothelial-reticular involvement, rapidly progressing to multiple organs dysfunction(5,9,10). Histologically, the three clinical syndromes are characterized by atypical Langerhans' cells which, associated with polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, and mainly eosinophils, lead to the formation of granulomas. In the early phase of the disease, aggregate of Langerhans' cells are found, frequently associated with eosinophils, although their presence is not essential for the diagnosis. In the chronic phase, the findings include lesions with few Langerhans' cells, associated or not with the presence of eosinophils(11,12). Electronic microscopy can detect Birbeck granules, cytoplasmic structures found exclusively in Langerhans' cells, and currently the definite diagnosis is immunohistochemically determined by the presence of CD-1 and S-100 markers(10,13). Imaging findings in cases of Langerhans' cell histocytosis are quite variable, and may present any radiographic feature, sometimes mimicking malignant diseases. Plain radiography is the primary method of investigation, and the most typical finding is a lytic lesion, with well- or ill-defined margins and bone destruction, usually centrally located in flat bones or in the diaphyseal region of long bones. Cortical bone destruction or expansion may be found, and the periosteal reaction is generally compact, although lamellar periosteal reaction may be found in young children. The evaluation by means of computed tomography allows confirming the presence of the lesion, defining the extent of cortical destruction and the degree of involvement of soft tissues. Additionally, this method is useful in cases where the bone lesion is situated in anatomically complex regions such as mastoid process, atlantoaxial joint, and posterior elements of vertebral bodies(6,10). Magnetic resonance imaging presents a high sensitivity, however its specificity is low. The lesion of eosinophilic granuloma presents iso/hyposignal on T1-weighted images, and hypersignal on T2-weighted images, and possibly enhancement after contrast agent injection. Magnetic resonance imaging also is useful for defining the extent of bone marrow and soft tissues involvement(13,14). The most significant prognostic factors in these cases are the patient's age and the lesion extent, the prognosis being worst in children younger than two years old, and in case of large lesions(15,16). Spontaneous resolution of focal bone disease may occur in some cases. The treatment for solitary lesions of long bones resulting from eosinophilic granulomas consists of curettage of the area and implantation of bone or methacrylate graft, or corticoid injection(17). The most significant differential diagnoses in this context are acute osteomyelitis and Ewing's sarcoma0(10,18). In cases of osteomyelitis, radiological alterations can be visualized 10 to 12 days after the onset of the disease, when edema of soft tissues can be observed. After 10 to 14 days, an illdefined, focal area of rarefaction in the metaphysis, with a "piecemeal" pattern of the bone marrow, progressing to lytic destruction and associated focal periosteal reaction. Ewing's sarcoma is a metaphyseal tumor that affects both flat and long bones, characterized by a lytic lesion with ill-defined margins, cortical invasion and periosteal reaction which can be lamellar, interrupted or present with Codman's triangle. Sclerotic lesions may be observed in 25% of cases. Differentiation, in these cases can be achieved by means of biopsy.

REFERENCES 1. Egeler RM, D'Angio GJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 1995;127:1–11. [ ] 2. Mirra JM. Histiocytoses. In: Mirra JM, Picci P, Gold RH, editors. Bone tumors: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic correlations. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1989: p.1021–60. [ ] 3. Mickelson MR, Bonfiglio M. Eosinophilic granuloma and its variations. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8:933–45. [ ] 4. David R, Oria RA, Kumar R, et al. Radiologic features of eosinophilic granuloma of bone. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:1021–6. [ ] 5. Stull MA, Kransdorf MJ, Devaney KO. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. RadioGraphics. 1992;12:801–23. [ ] 6. Kilborn TN, Teh J, Goodman TR. Pediatric manifestations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the clinical and radiological findings. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:269–78. [ ] 7. Fowles JV, Bobechko WP. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma in bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970; 52:238–43. [ ] 8. Broadbent V, Egeler RM, Nesbit ME Jr. Langerhans cell histiocytosis – clinical and epidemiological aspects. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1994;70:S11–6. [ ] 9. Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee on Histiocytic Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997; 29:157–66. [ ] 10. Azouz EM, Saigal G, Rodriguez MM, et al. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis: pathology, imaging and treatment of skeletal involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:103–15. [ ] 11. Basset F, Soler P, Hance AJ. The Langerhans' cell in human pathology. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1986;465: 324–39. [ ] 12. Leonidas JC. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. In: Taveras JM, Ferrucci JM, editors. Radiology: diagnosis, imaging, intervention. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1990. p.1–9. [ ] 13. Birbeck M, Breathnack A, Everall J. An electron microscope study of basal melanocytes and high-level clear cells (Langerhans cells) in vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;37:51–63. [ ] 14. Beltran J, Aparisi F, Bonmati LM, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma: MRI manifestations. Skeletal Radiol. 1993;22:157–61. [ ] 15. Berry DH, Gresik MV, Humphrey GB, et al. Natural history of histiocytosis X: a Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1986;14:1–5. [ ] 16. Meyer JS, Harty MP, Mahboubi S, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: presentation and evolution of radiologic findings with clinical correlation. RadioGraphics. 1995;15:1135–46. [ ] 17. Hoover KB, Rosenthal DI, Mankin H. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36: 95–104. [ ] 18. Woertler K. Benign bone tumors and tumor-like lesions: value of cross sectional imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1820–35. [ ]

* Study developed at Instituto de Radiologia do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (InRad/HC-FMUSP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil. |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554