Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 50 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2017

Vol. 50 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2017

|

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

|

|

A rare case of pneumorrhachis accompanying spontaneous pneumomediastinum |

|

|

Autho(rs): Luciana Mendes Araújo Borem1; Dimitrius Nikolaos Jaconi Stamoulis2; Ana Flávia Mundim Ramos2 |

|

|

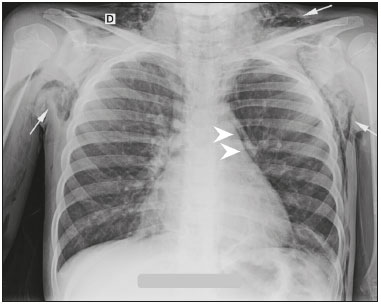

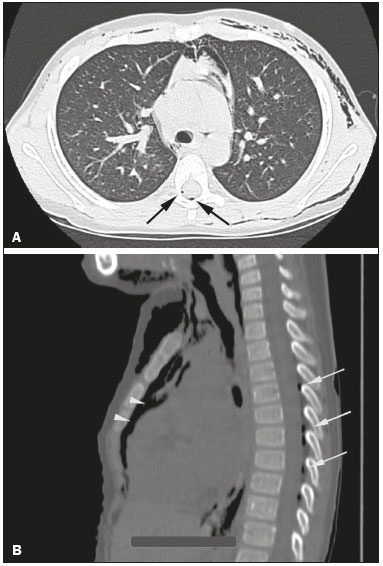

Dear Editor,

A 7-year-old female with dyspnea and edema of the neck, accompanied by a cough, was treated at another facility, where anti-inflammatory drugs and an inhaler were prescribed. The patient evolved to worsening of the dyspnea and cough, in addition to intercostal retraction and increased neck volume. She presented to our facility in satisfactory general health. On physical examination, the oropharynx showed no alterations, although there was bilateral edema of the neck and periorbital area, together with diminished breath sounds, sparse wheezing, respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min, intercostal retraction, and subcutaneous crackles on anterior/posterior thoracic palpation, without Hamman’s sign. A chest X-ray obtained at admission (Figure 1) showed pneumomediastinum and extensive subcutaneous emphysema. She underwent computed tomography (CT) of the chest (Figure 2), which revealed pneumorrhachis, a rare finding. The patient remained in the hospital for five days under supportive care, and there was complete remission of symptoms.  Figure 1. Posteroanterior chest X-ray showing pneumomediastinum (arrowheads), together with extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the supraclavicular and axillary regions (arrows).  Figure 2. CT of the chest in the axial (A) and sagittal (B) planes showing pneumorrhachis (arrows) and mediastinal emphysema (arrowheads). Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, also known as Hamman’s syndrome, is an uncommon condition in medical practice, occurring in approximately 1/30,000 hospital admissions(1) and in only 1% of asthma cases(2). Its main causes are intense physical exercise, labor (of childbirth), pulmonary barotrauma, diving to great depths, severe paroxysmal coughing, vomiting, asthma, inhalation of narcotics, bronchial asthma, and a slender body type(1,2). The pathophysiological hallmark of Hamman’s syndrome is alveolar overdistension and rupture, which results from high intra-alveolar pressure, low perivascular pressure, or both. After the initial event, the air freely penetrates the mediastinum during the respiratory cycle, in order to balance the pressure gradients(3,4). Known triggers include acute exacerbation of asthma and situations requiring the Valsava maneuver(4). The combination of spontaneous pneumomediastinum and pneumorrhachis is extremely rare(5,6). Possible causes of pneumorrhachis include use of the drug ecstasy, abscesses, asthma attacks, coughing fits, violent vomiting, epidural anesthesia, lumbar puncture, and thoracic or vertebral surgery or trauma(7,8). In extremely rare cases, meningitis or pneumocephalus can occur(7). Pneumorrhachis typically occurs directly, when atmospheric air reaches the epidural space by means of a needle or a penetrating wound from the spine, although it can occur indirectly, as in bronchial asthma. In the case of bronchial asthma, air from the rupture of a peripheral pulmonary alveolus leaks into the pulmonary perivascular interstitium and follows the path of least resistance of the mediastinum to the fascia of the neck. Due to the absence of fascial barriers, air crosses the neural foramen and deposits in the epidural space. In either situation, pneumorrhachis is usually asymptomatic and disappears spontaneously within a few weeks. Whereas CT allows direct visualization of the presence of air in the affected compartment(s), X-rays can reveal signs typical of pneumomediastinum, produced when the air leaving the mediastinum delineates the normal anatomical structures. Such signs include subcutaneous emphysema, the “sail sign” of the thymus, pneumopericardium, the “ring-around-the-artery” sign, the “continuous diaphragm” sign, and the “double bronchial wall” sign(3). REFERENCES 1. Lopes FPL, Marchiori E, Zanetti G, et al. Pneumomediastino espontâneo após esforço vocal: relato de caso. Radiol Bras. 2010;43:137-9. 2. Bote RP, Moreno AM, Núñez JMF, et al. Enfisema epidural associado a traumatismo torácico grave. Emergencias. 2008;20:70-1. 3. Fatureto MC, Santos JPV, Goulart PEN, et al. Pneumomediastino espontâneo: asma. Rev Port Pneumol. 2008;14:437-41. 4. van Veelen I, Hogeman PHG, van Elburg A, et al. Pneumomediastinum: a rare complication of anorexia nervosa in children and adolescents. A case study and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:171-4. 5. Nascimento J, Gomes M, Moreira C, et al. Caso radiológico. Nascer e Crescer. 2012;21:153-4. 6. Alves GRT, Silva RVA, Corrêa JRM, et al. Pneumomediastino espontâneo (síndrome de Hamman). J Bras Pneumol. 2012;38:404-7. 7. Aribas OK, Gormus N, Aydogdu Kiresi D. Epidural emphysema associated with primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:645-6. 8. Araujo MS, Fernandes FLA, Kay FU, et al. Pneumomediastino, enfi sema subcutâneo e pneumotórax após prova de função pulmonar em paciente com pneumopatia intersticial por bleomicina. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39:613-9. 1. Santa Casa de Montes Claros, Montes Claros, MG, Brazil 2. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM), Uberaba, MG, Brazil Mailing address: Dr. Dimitrius Nikolaos Jaconi Stamoulis Departamento de Radiologia e Diagnóstico por Imagem – UFTM Avenida Getúlio Guaritá, 130, Nossa Senhora da Abadia Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 38025-250 E-mail: dimitriusss@hotmail.com |

|

GN1© Copyright 2025 - All rights reserved to Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia e Diagnóstico por Imagem

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554