Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 46 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2013

Vol. 46 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2013

|

REVIEW ARTICLE

|

|

Computed tomography findings in patients with H1N1 influenza A infection |

|

|

Autho(rs): Viviane Brandão Amorim1; Rosana Souza Rodrigues2; Miriam Menna Barreto3; Gláucia Zanetti4; Edson Marchiori5 |

|

|

Keywords: Influenza A (H1N1); Pulmonary infection; Pulmonary viruses; Computed tomography. |

|

|

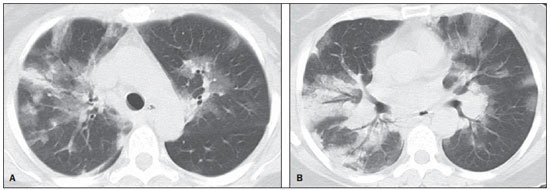

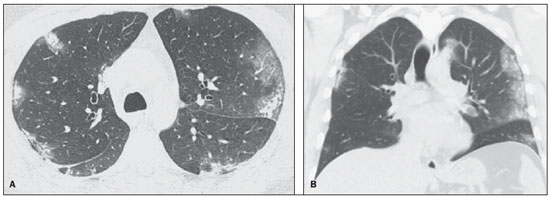

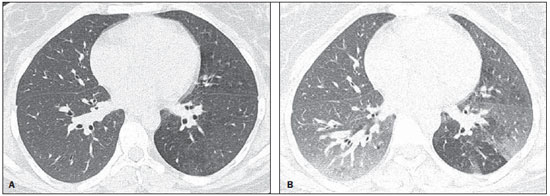

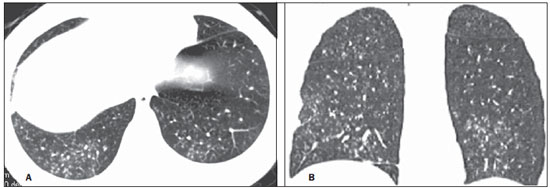

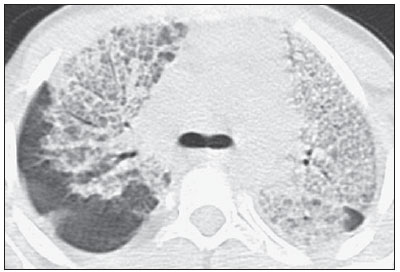

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

In April 2009, an epidemic of acute febrile respiratory illness caused by a new virus - influenza A (H1N1) - broke out. The first cases occurred in Mexico and the infection rapidly propagated throughout the world(1). In August 2010, 214 countries had already been hit by the infection, with more than 18,000 confirmed deaths(1,2). This new virus is directly or indirectly transmitted from person to person by means of respiratory secretions from infected individuals. The symptoms onset occurs in a period between 3 and 7 days following contact with the virus, and the transmission occurs mainly in indoor areas, even before the symptoms onset. The clinical manifestations of the infection are similar to those of the common influenza, and are many times self-limited. However, sometimes the respiratory symptoms may be exuberant, with respiratory failure and death(3). Chest radiography provides appropriate data to define the approach for most of the affected patients(4). But, many times, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is an important tool to determine the extent of pulmonary compromise, besides being useful in the evaluation of complications, mixed infections or failure in the response to appropriate therapy(5). Although the diagnosis of viral infection is based on the clinical signs and virus identification, familiarity with imaging findings of the disease may be useful in patients with atypical or baffling clinical signs, in whom the H1N1 infection has not been suspected. The present study is aimed at reviewing the most frequent pulmonary computed tomography findings in patients with proven infection by the influenza A (H1N1) virus. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS The influenza A (H1N1) virus caused the first pandemic in the 21st century. In August 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of the pandemic period. Even with end of the pandemic, the A/H1N1 2009 subtype continues raging around the globe, now causing focal outbreaks, as most people are protected against the virus, either because of natural infection in 2009 (it is estimated that up to 30% of the population may have experienced influenza caused by the A/H1N1 virus subtype) or vaccine exposure. The outbreaks have been occurring in practically every country of the world(6). Thus, the possibility of infection by the influenza A (H1N1) virus should be still considered in patients with influenza-like syndrome, particularly in those cases with risk factors for worse outcomes. The H1N1 influenza pandemic 2009 was caused by an influenza virus strain which had never affected humans until early that year. The etiologic agent is called influenza A (H1N1) virus of swine-origin(7). The transmission occurs by means of respiratory secretions containing the virus, which are scattered by small aerosol particles generated during sneezing, coughing or speaking(3). The infection lasts approximately one week and is characterized by the sudden onset of symptoms, such as high fever, muscle pain, headache, malaise, cough and runny nose. Most patients recover without the need of medical treatment. In very young children, in the elderly or in patients with comorbidities (pulmonary, metabolic and renal diseases, among others) the disease may evolve with complications(2,3). In spite of the end of the pandemic being declared by WHO in August 2010, there are still cases and focal outbreaks occurring all over Brazil(8,9). According to the Ministry of Health (MH), in 2011 about 5,000 cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in hospitalized patients were reported, with 181 (3.7%) of such cases being confirmed as influenza A (H1N1) virus. Among such confirmed cases, 21 (11.6%) patients progressed to death(8). In 2012, until November 7, among all patients admitted for SARS, influenza was responsible for 20.4% (3,978/19,531) and out of such cases, 65.5% were caused by the influenza A (H1N1) virus. The Southern and Southeastern regions recorded the highest number of cases in that period(9). CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS The infection by the influenza A (H1N1) virus presents a wide spectrum of clinical syndromes ranging from asymptomatic cases to fulminating viral pneumonia, respiratory failure and death(5). The wide majority of patients who seek medical assistance, present signs and symptoms similar to those observed in seasonal influenza patients. Generally there is fever and coughing, symptoms which are frequently followed by odynophagia, runny nose, myalgia and headache. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting and diarrhea occur more commonly than in seasonal influenza, particularly in adults. Occasionally, the influenza may cause bronchospasm or pneumonia(3). The usual outcome is spontaneous resolution in 7 days, although coughing, malaise and fatigue may last for a few weeks. Some cases may progress with complications(10). Dyspnea, tachypnea in children, chest pain, hemoptysis or purulent sputum, prolonged or recurrent fever, lethargy, dehydration and symptoms recurrence after an initial improvement are signs of unfavorable evolution or complications onset(3). Bacterial infections (sinusitis, otitis, pneumonia) are the most common complications in children and in elderly patients(3). The main clinical syndrome which leads to hospital and ICU admission is diffuse viral pneumonia associated with severe hypoxemia, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), shock and renal failure. Is progression is generally rapid, from 4 to 5 days after the disease onset, and many times intubation is required within the first 24 hours after admission(3). Bacterial coinfection may affect the clinical manifestations severity and the disease outcome. It was described in severe and fatal cases of other pandemics caused by the influenza virus (90% of the autopsies in the 1918 pandemic and approximately 75% of the autopsies in the 1957 pandemic) and in seasonal influenza(11,12). The incidence of bacterial pneumonia associated with the influenza A virus (H1N1) ranges from 29% to 55% of the cases(11-13). Such a coinfection plays a relevant role in the progression of the infection by the pandemic virus. DIAGNOSIS Most common laboratory findings include leukopenia with lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, mild to moderate increase in transaminase and lactic dehydrogenase (LDH)(2,14). Also, increase in creatine kinase may be observed in patients who progressed with myositis(15). According to the Ministry of Health, The laboratory test for the specific diagnosis of the pandemic influenza (H1N1) 2009 is indicated only in cases of SARS and in cases of influenza syndrome outbreak in closed communities, as per the epidemiological surveillance guidelines(14,16). The diagnostic technique recommended by WHO for laboratory confirmation of the influenza A (H1N1) virus is the real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The clinical material of choice is the secretion from both nostrils and from the oropharynx, collected by means of aspiration or by rayon swabs. The utilization of rayon swabs is not recommended for children under the age of 2 years. The secretion samples should preferably be collected at the 3rd day after the symptoms onset, before the beginning of the treatment with oseltamivir, and no later than the 7th day(14,16). Specimens collected from the lower respiratory tract, including secretion, endotracheal aspirate and bronchoalveolar lavage, may be more sensitive in those cases where the lower respiratory tract involvement predominates. Additionally, the virus may be detected in the blood, feces and in urine(17). Positive virus culture in respiratory secretions or other tissue specimens is the gold standard for the diagnosis of the virus(17). HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS The influenza A (H1N1) virus causes histopathological changes in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts. Apparently, the typical uncomplicated benign infections affect only the mucosa of the upper tracheobronchial tree(13). The histopathological findings are similar to those in pneumonias caused by other influenza viruses, therefore they are not pathognomonic(18). The influenza virus is a cytopathic virus which causes pulmonary injury, with diffuse involvement of the epithelium, and in the more severe cases resulting in bronchitis and/or necrotizing bronchiolitis and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD)(19). Autopsies on patients who died of pneumonia caused by the influenza A (H1N1) virus demonstrate that DAD is the main pulmonary change(11-13,18). The following findings are observed at the late stage of the disease: organizing DAD, fibrosis, type II pneumocytes hyperplasia, epithelial regeneration and squamous metaplasia, which are compatible with the fibroproliferative phase of ARDS and DAD(17). RADIOLOGICAL FINDINGS Chest evaluation by means of imaging methods has been the object of a recent series of publications in the Brazilian radiological literature(19-28). Radiological findings in cases of viral infections are nonspecific and depend upon the pathological process affecting the lung. Such findings reflect a wide range of histopathological characteristics, such as DAD (intra-alveolar edema, fibrin, and cellular infiltrates with hyaline membrane); intra-alveolar hemorrhages and interstitial infiltrate of inflammatory cells (either intrapulmonary or in the airways)(29,30). Chest radiography is normally the first imaging method utilized in the investigation of acute respiratory conditions(5), considering its wide availability, swiftness and low cost. Radiographic findings are not enough for a definitive diagnosis of viral pneumonia, but in association with clinical and laboratory data they can substantially improve the accuracy of the diagnosis(29). In viral pneumonias, chest radiographs may be either normal, or demonstrate the presence of unilateral or bilateral focal areas of consolidation; nodular opacities; bronchial walls thickening and small pleural effusions. Lobar consolidations are uncommon(29). Frequently, bilateral focal alveolar infiltrates are predominantly observed in the lung bases on radiographs of patients with pneumonia caused by the influenza A (H1N1) virus(15). Computed tomography (CT), especially HRCT, is an excellent method to evaluate pulmonary diseases with greater accuracy as compared with radiography. Currently, an increasing number of patients are being submitted to CT in cases where there is high clinical suspicion of viral infection and chest radiography is normal or dubious(5,29). Heussel et al.(31) have developed a study with febrile neutropenic patients and observed that in 48% of the cases where chest radiographs were normal, there were findings suggestive of pneumonia at CT. CT is also useful in the evaluation of complications in patients with known pneumonia which do not respond to appropriate therapy(5). At CT in patients affected by viral pneumonias, predominant findings include unilateral or bilateral ground-glass opacities, either in association or not with focal or multifocal consolidation areas. Ground-glass opacities and consolidation areas have a predominantly peribronchovascular and subpleural distribution, similarly to organizing pneumonia(5,29,30,32). Other common findings include micronodules, centrilobular nodules, "tree-in-bud" pattern, bronchial wall thickening and air trapping(29,30). Pulmonary hyperinflation is common due to associated bronchiolitis(5,30). The acute form of pneumonia with rapid progression shows a fast confluence consolidation caused by the diffuse alveolar damage, which may be homogeneous or irregular, unilateral or bilateral; besides ground-glass opacities or ill-defined centrilobular nodules(30). Main HRCT findings in patients affected by the influenza A (H1N1) virus include ground-glass opacities, consolidation or combined ground-glass opacity and consolidation (Figures 1 and 2)(5,18,33-40). The patients with consolidation present a worse clinical progression(5,18,33,34). The distribution of such changes is predominantly subpleural and peribronchovascular(5,33,35). There is a predilection for the lung bases(35,37).  Figure 1. HRCT showing areas of consolidation and ground-glass opacities in the upper (A) and lower lobes (B) of both lungs.  Figure 2. Axial HRCT (A) and coronal reformation (B) demonstrating ground-glass opacities with predominantly peripheral distribution. Marchiori et al.(5) have correlated the radiographic and tomographic findings in 20 patients with proven diagnosis of infection by the influenza A (H1N1) virus. Radiography and HRCT were performed on a single day. Chest radiography was normal in 4 patients, and bilateral consolidation was observed in the other patients. Main HRCT findings included ground-glass opacities (n = 12), consolidation (n = 2) and association of ground-glass opacities with consolidation (n = 6). In all the patients the changes were bilateral, with subpleural distribution (peripheral) in 13 cases and randomly distributed in 7 cases. Nodular opacities or lymph node enlargement were not observed. In the patients whose chest radiographs were normal, ground-glass opacities were seen at HRCT. The patients who presented consolidation at HRCT progressed unfavorably as compared with those who presented ground-glass opacities. Among the 8 patients who presented consolidation, 4 required mechanical ventilation and 3 died. The series developed by Grieser et al.(36) was aimed at evaluating whether the tomographic findings were valuable in predicting the prognosis for patients affected by the influenza A (H1N1) virus who presented early progression to ARDS. The authors analyzed the findings of 23 CTs and graded such changes according to a score based on their distribution and intensity in the six pulmonary zones, and the density of such findings was measured in Hounsfield units. On all such CTs, an association of ground-glass opacity and consolidation affecting both lungs was observed, without zone predominance in 17 patients, or with predominance in the lower lobes in 6 of the patients. As regards the grading of the findings, a higher score was observed in patients who died (9 patients; 39%), and was significantly lower in those patients who survived. The authors concluded that the utilized score had a prognostic value in the patients who progressed with ARDS. Toufen et al.(41) clinically and radiologically followed-up 4 patients affected by the pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus who progressed with ARDS. The patients underwent the exams during their hospital stay, between 1 and 2 months and 6 months after hospital discharge. All the patients presented diffuse ground-glass opacities at HRCT performed during their hospital stay, and improvement of such changes was observed 6 months after hospital discharge. None of the patients presented air trapping on HRCT expiratory phase images acquired after 6 months. As regards pulmonary function studies, 2 patients (50%) persisted with restrictive pulmonary pattern and all presented normal carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. The results were surprising, since the literature highlights pulmonary function anomalies in ARDS survivors after 6 months of progression, with low carbon monoxide diffusing capacity and residual changes suggestive of fibrosis at HRCT. In patients who achieve cure, regression of pulmonary opacities is generally observed during the convalescent phase and consolidation areas may occasionally progress to linear opacities(5,18,34). Such linear opacities probably represent organizing pneumonia(33,34,42,43). With the objective of comparing radiological findings during the acute and convalescent phases of the disease, Li et al.(18) have undertaken a serial analysis of HRCT findings in 70 patients affected by the influenza A (H1N1) virus. The authors divided the patients into two groups as follows: group 1 comprised severe cases which required admission to ICU or mechanical ventilation; and group 2 comprising patients who were admitted for a short period, with no need for mechanical ventilation. Ground-glass opacities were the predominant finding at the first week after the symptoms onset (95% of the patients), either in association or not with consolidation, with reduced frequency on the subsequent weeks. Air trapping was observed in only 9 of the patients who were submitted to mechanical ventilation. As regards the extent of the pulmonary involvement by the disease, such it was greater in the second week after the symptoms onset in both groups, with slow resolution in the following weeks. Greater pulmonary involvement was observed in group 1. Findings suggesting fibrosis (intralobular lines, reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, parenchymal bands and irregular linear opacities) were already observed in the first week after the symptoms onset, with later increase in their frequency. The second week after the symptoms was the period where a higher number of intralobular lines and reticular opacities in association with ground-glass opacities were observed. The mean timing for findings suggestive of fibrosis was 22.6 ± 15.8 days. After one month from the symptoms onset, the patients presented improvement of the fibrosis-related findings, demonstrating capacity of pulmonary regeneration. Marchiori et al.(34) followed-up on the clinical and radiological progression of a patient affected by influenza A (H1N1) virus who completely recovered from the infection. In such a case, the findings were similar to those reported by Li et al.(18). Initially, HRCT demonstrated ground-glass opacity and consolidation. During the convalescent phase of the disease, HRCT demonstrated linear opacities in the place where previously ground-glass opacity and consolidation were found. With the treatment, the patient progressed with complete remission of the symptoms. Follow-up HRCT was normal three months after the symptoms onset. During the treatment and convalescent phase, the presence of persistent opacities at chest radiography may not be informative enough to differentiate disease progression from healing. In such cases, HRCT is useful in the recognition and characterization of the stage of disease, monitoring its progression and response to treatment, as well as identifying complications(34). Alterations which reflect small airways compromise commonly associated with viral infections, such as centrilobular nodules, "tree-in-bud" pattern, air trapping and bronchial wall thickening, are also described in infection by the influenza A (H1N1) virus, but they are uncommon(35,37,44,45). Ketai(46) suggests that patients with infection by the A (H1N1) virus develop small airway disease early in the course of the infection, and then improve clinically or progress to a more severe pattern of pulmonary involvement which leads them to seek medical assistance. The presence of peribronchovascular pattern in many of those more severely ill patients is suggestive of large airways involvement rather than small airways involvement. Contrary to what is suggested by Ketai(46), that the small airways involvement occurs at the early stage of the disease, Marchiori et al.(35) have followed-up a female 38-yearold patient infected with the influenza A (H1N1) virus who progressed with small airways involvement at the convalescent phase, with clinical and radiological findings suggestive of bronchiolitis. In the acute phase of the disease, the patient presented bilateral consolidation at chest radiography, and at HRCT, bilateral consolidation and ground-glass opacity with predominantly basal peribronchovascular distribution. After three months, the patient presented with dyspnea, and HRCT demonstrated complete regression of the opacities and presence of air trapping, more noticeable at the expiratory phase (Figure 3). Spirometry confirmed the findings of small airways involvement.  Figure 3. Axial HRCT (inspiration) (A) and expiration (B) identifying air trapping in the lower lobe of the left lung. Involvement of small airways was described in two series developed with immunocompromised patients infected with the influenza A (H1N1) virus(37,44). In one of such studies, Elicker et al.(44) evaluated 20 CT images of 8 patients. Bronchial wall thickening was found on all the imaging studies. The second most frequent finding was consolidation, observed in 85% of the CT scans, with more commonly peripheral distribution (50%) and affecting the lower lobes (90%). Ground-glass opacities were seen on 65% of the studies (13/20). Centrilobular nodules were present on 8 of the 20 CT studies (40%), 2 of them with the "tree-in-bud" pattern (Figure 4). In the other study, Rodrigues et al.(37) have also evaluated immunocompromised patients, and like Elicker et al.(44), described the involvement of small airways. The authors analyzed tomographic findings in 8 cancer patients with febrile neutropenia and infection with the influenza A (H1N1) virus. In such a series, the predominant findings were ground-glass opacities (all patients) and consolidation (7/8 patients). Air space nodules were observed in 6 patients. Such finding related to the influenza A (H1N1) virus is not commonly reported in the literature, a fact which the authors attribute to an alternative interpretation of air space nodules as focal areas of consolidation. Centrilobular nodules, "tree-in-bud" pattern and bronchial wall thickening were found in 25% of the patients (2/8). One patient presented the mosaic pattern of attenuation (Figure 5). The authors classified the findings according to the predominating pattern, as follows: pattern characteristic of pneumonia in 5 patients, bronchitis/bronchiolitis in 2 patients, and chronicity in 1 patient. Amongst the patients with pneumonic pattern, in 4 the findings predominated in the lower thirds of the lungs.  Figure 4. HRCT in axial view (A) and coronal reformation (B) demonstrating multiple small, centrilobular nodules, some of them configuring the "tree-in-bud" pattern distributed mainly in the posterior portions of the lung.  Figure 5. Axial HRCT at the level of the carina demonstrating ground-glass attenuation areas associated with interlobular septal thickening in both lungs (crazy paving pattern). Tanaka et al.(38) compared the HRCT findings in 10 patients affected by the seasonal influenza virus and in 19 patients with the pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. Ground-glass opacities were the most common findings observed in all the cases of seasonal flu and in 84.6% of the cases of pandemic flu, with no significant difference between the groups. The crazy paving pattern was most frequently seen in the seasonal flu cases (70% versus 25%), as well as the mosaic pattern of attenuation (80% versus 15.8%) and interlobular septal thickening (60% versus 21.1%). On the other hand, air space consolidation and mucoid impaction were most frequently observed in patients affected by the pandemic flu (84.2% versus 40%, and 52.6% versus 10%, respectively). Consolidation with loss of pulmonary volume was frequent in pandemic influenza (62.5%). According to the authors, the presence of mucoid impaction and loss of pulmonary volume indicate that the infection by the influenza A (H1N1) virus tends to affect both the large and small airways, as well as the lung parenchyma, causing excessive production of mucus which results in loss of volume and atelectasis. Other common findings for both types of infection in the series developed by Tanaka et al.(38) were centrilobular nodules and bronchial wall thickening. The frequency of centrilobular nodules in patients affected by the pandemic virus (68.4%) in that study is in disagreement with other studies which suggested the infrequency of small airways involvement by such an infection(5,18,34). For the authors, one of the reasons why centrilobular opacities are rarely seen, is the fact that this small abnormality may be obscured in patients with more extensive disease. Another cause for such a fact, in agreement with Ketai(46), would be that the small airways involvement would happen early in the course of the disease, as the patients in the study had easy and fast access to the health system assistance. Marchiori et al.(33) have correlated tomographic and histopathological findings in 6 patients with proven infection by the A (H1N1) virus which progressed to death with no clinical, bacteriological or histopathological evidence of superimposed bacterial infection. The main tomographic findings were multifocal or diffuse, bilateral consolidation (100%), either associated or not with ground-glass opacities (50%). The dominant pathological characteristic was DAD with development of hyaline membrane (83%), associated with edema, hemorrhage, alveolar and interstitial inflammation, and bronchiolitis. The patient who survived the longest presented findings of organizing pneumonia at HRCT performed 15 days after the first scan. In the correlation with HRCT, the consolidation areas corresponded, at microscopy, to alveolar filling by edema, inflammatory or hemorrhagic exudate. Ground-glass opacities corresponded to the presence of alveolar septal thickening by inflammation or edema and/or partial air spaces filling. Pleural effusion, when observed, is small to moderate in volume(5,18,37). Lymph node enlargement generally is not observed. There are some reports in the literature on the occurrence of pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax. Parenchymal damage predisposes to the development of cysts, which may break open, causing development of extra-alveolar air collections. Such free air may dissect, causing pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum(33,44). The similarity between radiological patterns in pulmonary infections by the influenza A (H1N1) virus and SARS was highlighted by some authors(18,46). At early phases of both diseases, the viruses cause alveolar inflammation and interstitial edema, which result in ground-glass opacities as dominant radiographic finding, many times with subpleural distribution(18). In both diseases, the severe cases may rapidly demonstrate pathological and radiological characteristics of diffuse alveolar damage or even of ARDS(18). Additionally, in those diseases, the presence of centrilobular nodules, "tree-in-bud" pattern, excavation and mediastinal or hilar lymph node enlargement is not common(18). In patients affected by acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, the presence of ground-glass opacities at HRCT is frequently found in pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci. The possibility of infection by the influenza A (H1N1) virus should also be considered(33,47). Viral pneumonia caused by the influenza A (H1N1) virus complicated by bacterial coinfection represents a diagnostic challenge for the radiologist, as extensive consolidation may manifest in cases of pneumonia caused by the pandemic virus. In such cases, and depending on of clinical and laboratory test results, the possibility of secondary bacterial infection or the pulmonary manifestation of ARDS should be considered(33). REFERENCES 1. World Health Organization. Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1). [acessado em 21 de junho de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/h1n1_donor_032011.pdf. 2. Cao B, Li XW, Mao Y, et al. Clinical features of the initial cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2507-17. 3. Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, et al. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1708-19. 4. Aviram G, Bar-Shai A, Sosna J, et al. H1N1 influenza: initial chest radiographic findings in helping predict patient outcome. Radiology. 2010;255:252-9. 5. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, et al. High-resolution computed tomography findings from adult patients with Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:93-8. 6. Ministério da Saúde. Portal da Saúde. MS alerta sobre condutas frente a casos de gripe. 15 de julho de 2012. [acessado em 8 de setembro de 2012]. Disponível em: http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/aplicacoes/noticias/default.cfm?pg=dspDetalheNoticia&id_area=124&CO_NOTICIA=14037. 7. Zimmer SM, Burke DS. Historical perspective - Emergence of influenza A (H1N1) viruses. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:279-85. 8. Secretaria Estadual da Saúde de São Paulo. Centro de Vigilância Epidemiológica "Prof. Alexandre Vranjac". Situação epidemiológica da influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 e vigilância sentinela da influenza. [acessado em 10 de setembro de 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.cve.saude.sp.gov.br/htm/resp/pdf/IF12_influ0902.pdf. 9. Ministério da Saúde. Portal da Saúde. Boletim informativo de Influenza: semana epidemiológica 44. 12 de novembro de 2012. [acessado em 16 de novembro de 2012]. Disponível em: http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/noticia/8100/785/boletim-informativo-de-influenza:-semana-epidemiologica-44.html. 10. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Brasil. Protocolo de tratamento de Influenza - 2012. [acessado em 8 de setembro de 2012]. Disponível em: http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/portalsaude/arquivos/protocolo_de_tratamento_influenza_ms_2012.pdf. 11. Mauad T, Hajjar LA, Callegari GD, et al. Lung pathology in fatal novel human influenza A (H1N1) infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:72-9. 12. Shieh WJ, Blau DM, Denison AM, et al. 2009 Pandemic influenza A (H1N1): pathology and pathogenesis of 100 fatal cases in the United States. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:166-75. 13. Gill JR, Sheng ZM, Ely SF, et al. Pulmonary pathologic findings of fatal 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral infections. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:235-43. 14. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Brasil. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Guia de vigilância epidemiológica (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos). 7ª ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2009. 15. Perez-Padilla R, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S, et al. Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:680-9. 16. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Brasil. Protocolo de manejo clínico e vigilância epidemiológica da Influenza. Versão III. [acessado em 14 de março de 2011]. Disponível em: http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/protocolo_de_manejo_clinico_05_08_2009.pdf. 17. Cheng VC, To KK, Tse H, et al. Two years after pandemic influenza A/2009/H1N1: what have we learned? Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:223-63. 18. Li P, Zhang JF, Xia XD, et al. Serial evaluation of high resolution computed tomography findings in patients with pneumonia in novel swine origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:729-35. 19. Bozi LC, Severo A, Marchiori E. Pulmonary metastatic calcification: a case report. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:297-9. 20. Souza RC, Marchiori E, Zanetti G, et al. Spontaneous regression of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a case report. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:294-6. 21. Melo ASA, Marchiori E, Capone D. Tomographic and pathological findings in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:220-4. 22. Moraes CS, Queiroz-Telles F, Marchiori E, et al. Review of lung radiographic findings during treatment of patients with chronic paracoccidioidomycosis. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:20-8. 23. Koenigkam-Santos M, Barreto ARF, Chagas Neto FA, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: major radiologic findings in a series of 22 histopathologically confirmed cases. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:191-7. 24. Cerci JJ, Takagaki TY, Trindade E, et al. 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron-emission tomography is cost-effective in the initial staging of non-small cell lung cancer patients in Brazil. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:198-204. 25. Almeida LA, Barba MF, Moreira FA, et al. Computed tomography findings of pulmonary tuberculosis in adult AIDS patients. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:13-9. 26. Mohan K, McShane J, Page R, et al. Impact of 18F-FDG PET scan on the prevalence of benign thoracic lesions at surgical resection. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:279-82. 27. Chojniak R, Pinto PNV, Ting CJ, et al. Computed tomography-guided transthoracic needle biopsy of pulmonary nodules. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:315-20. 28. Rodrigues RS, Capone D, Ferreira Neto AL. High-resolution computed tomography findings in pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:225-32. 29. Franquet T. Imaging of pulmonary viral pneumonia. Radiology. 2011;260:18-39. 30. Kim EA, Lee KS, Primack SL, et al. Viral pneumonias in adults: radiologic and pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2002;22(Spec No):S137-S149. 31. Heussel CP, Kauczor HU, Heussel G, et al. Early detection of pneumonia in febrile neutropenic patients: use of thin-section CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1347-53. 32. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, et al. High-resolution computed tomography findings in a patient with Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia [Letter to the Editor]. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:85-6. 33. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Fontes CA, et al. Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia: high-resolution computed tomography-pathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:e500-4. 34. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Mano CM, et al. Follow-up aspects of Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia: the role of high-resolution computed tomography in the evaluation of the recovery phase. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:587. 35. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Mano CM. Swine-origin Influenza A (H1N1) viral infection: small airways disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W317. 36. Grieser C, Goldmann A, Steffen IG, et al. Computed tomography findings from patients with ARDS due to Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:389-94. 37. Rodrigues RS, Marchiori E, Bozza FA, et al. Chest computed tomography findings in severe influenza pneumonia occurring in neutropenic cancer patients. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67:313-8. 38. Tanaka N, Emoto T, Suda H, et al. High-resolution computed tomography findings of influenza virus pneumonia: a comparative study between seasonal and novel (H1N1) influenza virus pneumonia. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30:154-61. 39. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, D'Ippolito G, et al. Swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viral infection: thoracic findings on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:723-8. 40. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, D'Ippolito G. Crazy-paving pattern on HRCT of patients with H1N1 pneumonia. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:573-5. 41. Toufen C Jr, Costa EL, Hirota AS, et al. Follow-up after acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by influenza a (H1N1) virus infection. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:933-7. 42. Marchiori E, Hochhegger B, Zanetti G. Organising pneumonia as a late abnormality in influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:841. 43. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Ferreira Francisco FA, et al. Organizing pneumonia as another pathological finding in pandemic influenza A (H1N1). Med Intensiva. 2012 Oct 4. doi: 10.1016/j.medin. 2012.08.002. 44. Elicker BM, Schwartz BS, Liu C, et al. Thoracic CT findings of novel influenza A (H1N1) infection in immunocompromised patients. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:299-307. 45. Verrastro CGY, Abreu Junior L, Hitomi DZ, et al. Manifestations of infection by the novel influenza A (H1N1) virus at chest computed tomography. Radiol Bras. 2009;42:343-8. 46. Ketai LH. Conventional wisdom: unconventional virus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1486-7. 47. Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, et al. High-resolution computed tomography findings in a patient HIV-positive with swine-origin Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:179. 1. Specialization, Fellow Master degree of Radiology, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 2. PhD, Physician at Unit of Radiodiagnosis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and Instituto D'Or de Pesquisa, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 3. PhD, Physician at Unit of Radiodiagnosis, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 4. PhD, Professor, Faculdade de Medicina de Petrópolis, Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil 5. PhD, Associate Professor of Radiology, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil Mailing Address: Dr. Edson Marchiori Rua Thomaz Cameron, 438, Valparaíso Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil, 25685-120 E-mail: edmarchiori@gmail.com Received January 4, 2013. Accepted after revision March 14, 2013. Study developed at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554