Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 46 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2013

Vol. 46 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2013

|

REVIEW ARTICLES

|

|

Congenital inferior vena cava anomalies: a review of findings at multidetector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging |

|

|

Autho(rs): Catherine Yang1; Henrique Simão Trad2; Silvana Machado Mendonça3; Clovis Simão Trad4 |

|

|

Keywords: Inferior vena cava; Congenital abnormalities; Venous thrombosis. |

|

|

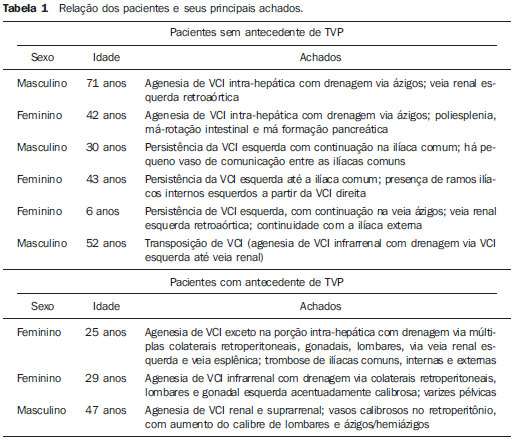

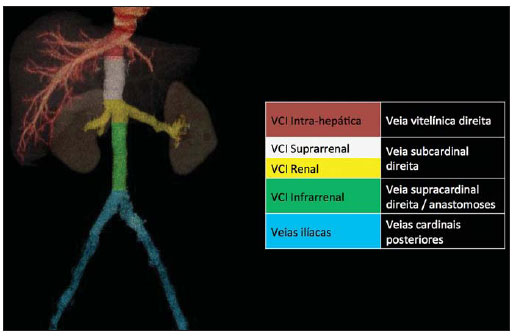

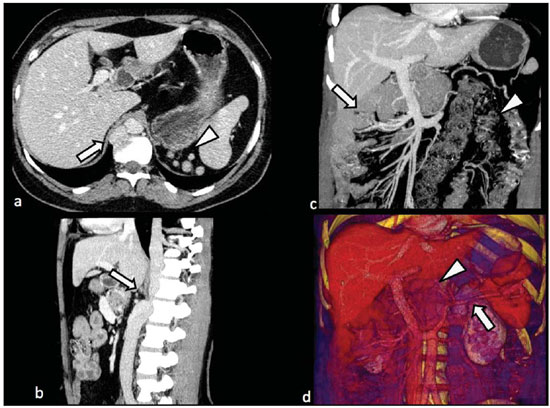

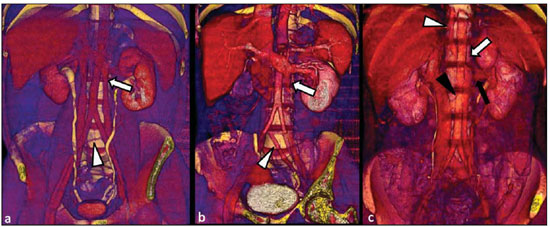

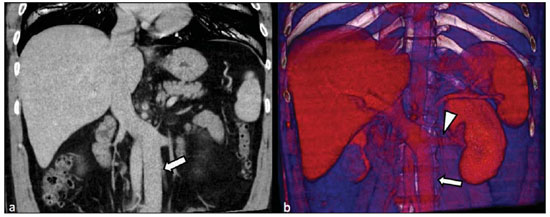

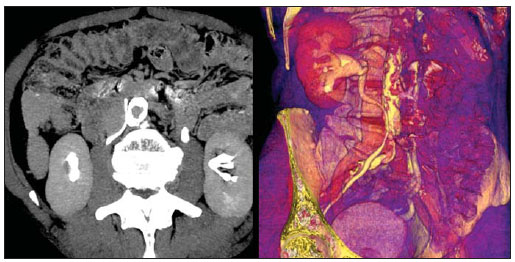

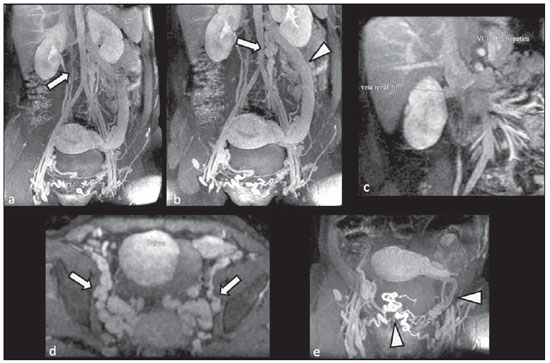

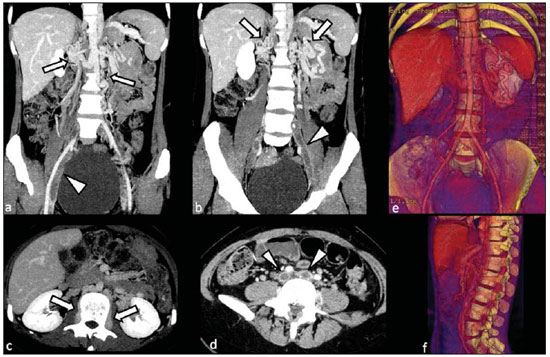

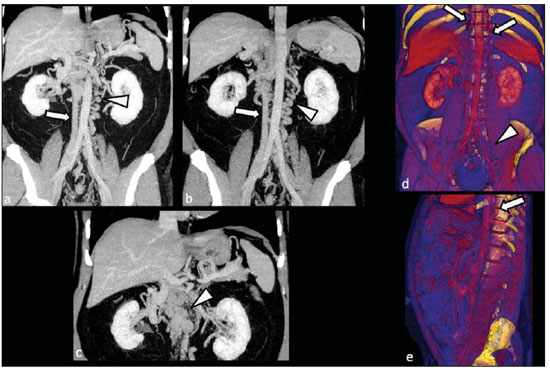

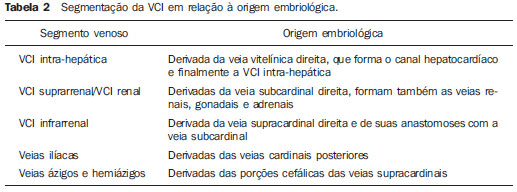

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

Congenital anomalies of the inferior vena cava (IVC) are uncommon, occurring in up to 8.7% of the population, as anomalies of the left renal vein are considered(1). With a complex embryonic development, originated from multiple embryonic structures, several anatomic variations of the venous return from the abdomen and lower limbs may occur(1–6). Some of these anomalies have significant clinical implications associated with other congenital anomalies, history of lower limb venous thrombosis and hematuria, sometimes determining changes in surgical planning(3,7–10). With the availability of multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) volumetric techniques, the demonstration of IVC anomalies became easier(4–6,11). However, it is not uncommon for such findings not being described on radiological reports, a fact that may negatively impact the approach to patients. In the present study, a simplified review of IVC embryology is made, demonstrating the main congenital anomalies, with evaluation, presentation, and discussion of ten cases. Computed tomography (CT) and MRI studies performed between 2008 and 2010 in ten patients with IVC anomalies were retrospectively reviewed. All the CT images were acquired in a 16-row multidetector equipment, with volumetric acquisition of 1.25 mm-thick slices without spacing, after intravenous injection of 100 ml iodinated contrast agent. The MRI studies were performed in 1.5 tesla high-field equipment, with acquisition of T1-and T2-weighted images acquisition, MRI angiography and contrast-enhanced volumetric gradient-echo, delayed phase sequences. Among the ten patients, five were men and five were women, with ages ranging from 6 to 77 years (median of 42.5 years). Three patients had a history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) of lower limbs, with ages of 25, 29 and 47 years (median of 29 years), and were submitted to the exams in order to clarify their condition. The remaining patients were submitted to the exams for other reasons, such as abdominal pain, hematuria and tumor staging. Among the seven patients with no DVT history two presented agenesis of the IVC intrahepatic portion, three presented double IVC, one presented transposition of the IVC and another presented retrocaval ureter. The median age of such patients was 43 years, revealing that the anomalies without relevant clinical implications have a tendency to be incidentally found during investigations performed for other reasons. In such a group, one 30-year old patient had agenesis of the intrahepatic portion of the IVC associated with polysplenia, intestinal malrotation and pancreatic malformation. Among the three patients with a history of DVT, one presented agenesis of the infrarenal portion only, another presented agenesis of the whole IVC and preserved intrahepatic portion only; and the third patient presented agenesis of the renal and suprarenal portions of the IVC. In the three cases, multiple, small retroperitoneal collateral vessels could be visualized. Further details on such findings are described on Table 1 and on Figures 2 thru 8.   Figure 1. Three-dimensional reconstruction with volume rendering. The anatomic segments of the IVC are separately colored, with highlighted embryonic origins.  Figure 2. Intrahepatic IVC agenesis associated with polysplenia and intestinal malrotation. a: Dilated azygos vein on the axial section (arrow) and polysplenia (arrowhead). b: Sagittal MIP – IVC continuation with retrocrural, calibrous azygos vein (arrow); c: Coronal MIP – intestinal malrotation (arrow indicates small bowel loops; arrowhead indicates the colon). d: 3D coronal view – short pancreas (arrowhead) with splenic vein in inferior pathway (arrow).  Figure 3. Persistent left IVC. Case 1 (a) – Left IVC draining into the left renal vein (arrow); small vessel anastomosis between the common iliac veins (arrowhead); Case 2 (b) – Left IVC draining into the left renal vein (arrow); branches from the left internal iliac joining the right IVC (arrowhead). Case 3 (c) – Left IVC with superior retroaortic pathway (white arrow) in continuation with the azygos vein (white arrowhead); left renal vein draining into the left IVC (black arrow) and there is a retroaortic communication between the inferior venae cavae, on the topography of retroaortic left renal vein (black arrowhead).  Figure 4. IVC transposition Coronal MIP (a) and 3D coronal image (b) demonstrate left IVC (arrows) draining into the left renal vein (arrowhead), anteriorly to the aorta. Absent right infrarenal IVC. The IVC is normally positioned at right of the renal, suprarenal and intrahepatic portions.  Figure 5. Retrocaval ureter. Right proximal ureter with posterior pathway to the IVC, crossing between the IVC and the middle third of the abdominal aorta.  Figure 6. Agenesis of infrarenal IVC. MRI angiography MIP reconstruction of abdomen – Agenesis of infrarenal IVC (arrow on a); dilated retroperitoneal veins and markedly calibrous left gonadal vein (arrow and arrowhead on b); magnification of the IVC occlusion area in the renal/infrarenal transition (c); pelvic varices (arrows in d) and varices on the lower abdominal wall (arrowheads on e).  Figure 7. Agenesis of suprarenal, renal and infrarenal IVC. Coronal MIP (a,b) – presence of extensive, calibrous collaterals in the retroperitoneum (arrows); thrombosed iliac veins (arrowheads). Axial MIP (c,d) – presence of calibrous collaterals in the retroperitoneum with increased caliber of the lumbar veins (arrows on c); thrombosed common iliac veins (arrowheads on d). 3D reconstruction – lumbar and retroperitoneal collaterals.  Figure 8. Agenesis of suprarenal and renal IVC. Coronal MIP (a,b,c) – infrarenal IVC (arrows) visible up to the renal hilum, with ill-defined suprarenal portion, and multiple calibrous vessels in the retroperitoneum (arrowheads). 3D reconstruction – calibrous, lumbar and retroperitoneal vessels, with increased caliber of the azygos and hemiazygos veins (arrows) pelvic varices (arrowheads). EMBRYOLOGY At later phases of its embryonic development, the IVC may be divided into four segments: hepatic, suprarenal, renal and infrarenal, originating from different embryonic structures. In a simplified way, the IVC originates from three pairs of veins, namely, postcardinal veins, subcardinal veins and supracardinal veins, which are dominant in the fourth, sixth and eighth gestational weeks, respectively. From the beginning through the end of the ontogenesis of the IVC, the pairs of embryonic veins present partial regression and anastomosis, contributing to the development of retroperitoneal vascular structures of the adult (Table 2 and Figure 1).  IVC ANOMALIES Intrahepatic IVC agenesis with azygos/hemiazygos continuation Embryonically, there is a developmental failure of the subcardinal-hepatic anastomosis between the suprarenal and hepatocardiac segments(1,6). Consequently, blood is deviated to the retrocrural azygos vein which is dilated up to the arch, which joins the superior vena cava in the right paratracheal space. The posthepatic segment drains the suprahepatic veins directly into the right atrium. Such an anomaly was classically described as being associated with polysplenia/asplenia and heterotaxy syndromes, with congenital cardiopathies and intestinal malrotation (Figure 2)(1,4,6,8). In such syndromes, the set of findings is variable from patient to patient, with reports of incidental findings, like in the case of the patient on Figure 2. With increasing utilization of imaging methods, such anomaly is found in asymptomatic patients with no other associated anomaly. Persistent left IVC It results from the persistence of right and left supracardinal veins, with two venae cavae around the infrarenal aorta(1,4,6). Typically, the left IVC ends at the left renal vein, which anteriorly crosses the aorta to join the IVC (Figure3). Variations may occur, as in the case presented at Figure 3c, with retroaortic left renal vein and left IVC continuation with the azygos vein. The left ICV continues with the iliac veins, with variations in the anastomosis with the internal and external common iliac veins(2). Transposition of the IVC It results from the regression of the right supracardinal vein and persistence of the left supracardinal vein. Typically, the left IVC ends at the left renal vein, which anteriorly crosses the aorta and forms a supra-renal IVC at right (Figure 4)(1). Retroaortic/circumaortic left renal vein The left renal vein derives from the intersubcardinal anastomosis, which courses anteriorly to the aorta. Retroaortic left renal vein (1.7% to 3.4% of the individuals) occurs by regression of the intersubcardinal anastomosis and renal drainage through retroaortic intersupracardinal anastomosis(1,3). The persistence of the two anastomoses results in a renal vein coursing anteriorly and another posteriorly to the aorta (prevalence of 2.4% to 8.7%), with the retroaortic vein caudal in relation to the pre-aortic vein(1) (Figure 3c). Retrocaval ureter It occurs exclusively in the right ureter and is one of the few IVC anomalies that may be symptomatic(1,4). Along the development of the infrarenal IVC there is regression of the right supracardinal vein, which courses posteriorly and medially to the ureter, originating from the right posterior cardinal vein, which, by its turn, is anteriorly located in relation to the ureter, which is medially displaced (Figure 5). The ureter is fixed between the IVC and the aorta, with the possibility of ureteral stenosis, upstream hydronephrosis and recurrent urinary infections. Subhepatic IVC agenesis Agenesis of subhepatic segments of the inferior vena cava may occur, involving the suprarenal, renal and infrarenal segments(1,4,7). In the present series, the three cases with history of lower limbs venous thrombosis, the findings were agenesis of subhepatic segments, without definition of single calibrous retroperitoneal vessel which would assist in venous return. Multiple calibrous venous collaterals were visualized in the retroperitoneum, including gonadal veins, lumbar and pelvic varices, with increased caliber of the azygos/ hemiazygos system (Figures 6 thru 8). IVC ANOMALIES AND CLINICOSURGICAL IMPLICATIONS Left-sided IVC may cause misdiagnosis with para-aortic lymph node enlargement, and may cause difficulties in the transjugular approach for IVC filter implantation. Also, it should be suspected whenever there is recurrent pulmonary thromboembolism in patients with implanted IVC filter. Anomalies of (retroaortic and circumaortic) left renal vein have clinical relevance mainly in surgical planning and in renal vein catheterization. On rare occasions the compression of the retroaortic renal vein may result in periureteral varices, venous hypertension and hematuria. Anomalies of the IVC were recognized as a possible risk factor for lower limb thrombosis, particularly in young adults. In some cases, the inappropriate venous return increases the pressure, leading to blood stasis in lower extremities and development of varices. Thrombosis occurs bilaterally in 50% of cases. An exuberant network of collaterals is generally identified, with prominent azygos and hemiazygos veins, ascending lumbar veins, internal paravertebral venous plexus and anterior abdominal wall veins. Markedly dilated lumbar veins may cause lumbar pain. CONCLUSION The evaluation of the retroperitoneum and its vessels is of extreme importance in the investigation of the abdomen. In spite of being uncommon, congenital IVC anomalies may cause difficulties in the interpretation of axial images. A basic knowledge of embryology and on the main congenital IVC anomalies is required for the correct interpretation and description by the radiologist, with special emphasis on alterations with possible clinical and surgical implications. REFERENCES 1. Kellman GM, Alpern MB, Sandler MA, et al. Computed tomography of vena caval anomalies with embryologic correlation. Radiographics. 1988;8:533–56. 2. Morita S, Higuchi M, Saito N, et al. Pelvic venous variations in patients with congenital inferior vena cava anomalies: classification with computed tomography. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:974–9. 3. Royal SA, Callen PW. CT evaluation of anomalies of the inferior vena cava and left renal vein. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:759–63. 4. Kandpal H, Sharma R, Gamangatti S, et al. Imaging the inferior vena cava: a road less traveled. Radiographics. 2008;28:669–89. 5. Fernandez-Cuadrado J, Alonso-Torres A, Baudraxler F, et al. Three-dimensional contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography of congenital inferior vena cava anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14:226–32. 6. Bass JE, Redwine MD, Kramer LA, et al. Spectrum of congenital anomalies of the inferior vena cava: cross-sectional imaging findings. Radio-graphics. 2000;20:639–52. 7. Gayer G, Luboshitz J, Hertz M, et al. Congenital anomalies of the inferior vena cava revealed on CT in patients with deep vein thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:729–32. 8. Fulcher AS, Turner MA. Abdominal manifestations of situs anomalies in adults. Radiographics. 2002;22:1439–56. 9. Saad WE, Saad N. Computer tomography for venous thromboembolic disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45:423–45, vii. 10. Applegate KE, Goske MJ, Pierce G, et al. Situs revisited: imaging of the heterotaxy syndrome. Radiographics. 1999;19:837–54. 11. Sheth S, Fishman EK. Imaging of the inferior vena cava with MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:1243–51. 1. Specialist in Radiology and Imaging Diagnosis, Fellow PhD degree, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRPUSP), Radiologist at CEDIRP – Central de Diagnóstico Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil 2. Titular Member of Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia e Diagnóstico por Imagem (CBR), Radiologist at CEDIRP – Central de Diagnóstico Ribeirão Preto, Physician Assistant at Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (HC-FMRPUSP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil 3. Specialist in Radiology and Imaging Diagnosis, Radiologist at CDPI – Clínica de Diagnóstico Por Imagem, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil 4. PhD, Titular Member of Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia e Diagnóstico por Imagem (CBR), Radiologist and Responsible Technician at CEDIRP – Central de Diagnóstico Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil Mailing Address: Dr. Henrique Simão Trad Rua Maestro Vila Lobos, 515, Jardim São Luiz Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil, 14020-440 E-mail: hstrad@terra.com.br Received August 5, 2012. Accepted after revision January 4, 2013. * Study developed at CEDIRP – Central de Diagnóstico Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil. |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554