Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 52 nº 6 - Nov. / Dec. of 2019

Vol. 52 nº 6 - Nov. / Dec. of 2019

|

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

|

|

Relationship between right atrium area and right ventricular ejection fraction on magnetic resonance imaging: comparison with other prognostic markers in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension |

|

|

Autho(rs): Marcelo M. Mello1,2,a; Guilherme Watte2,3,b; Stephan Altmayer2,c; Yana L. R. Pallaoro2,d; Fernanda B. Spilimbergo1,e; Daniela C. Blanco3,f; Gisela M. B. Meyer1,g; Edson Marchiori4,h; Bruno Hochhegger2,i |

|

|

Keywords: Hypertension, pulmonary; Magnetic resonance imaging; Cardiac catheterization; Echocardiography. |

|

|

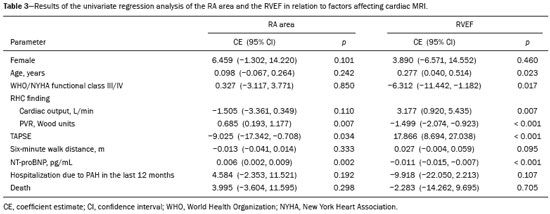

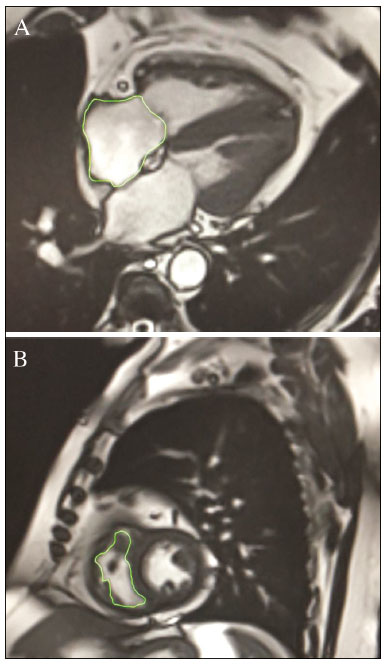

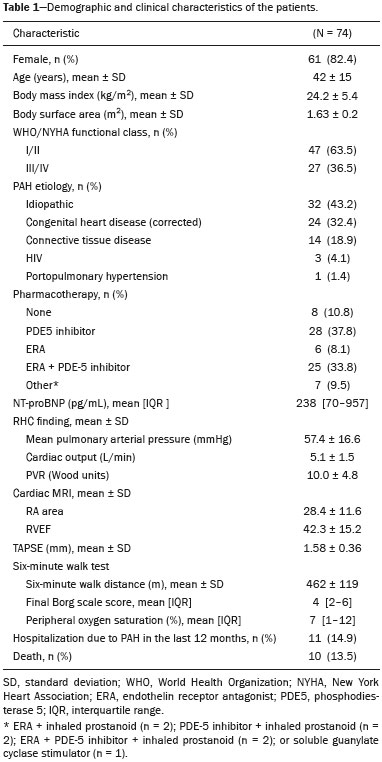

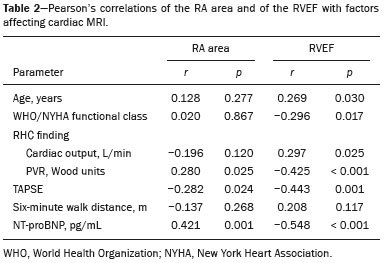

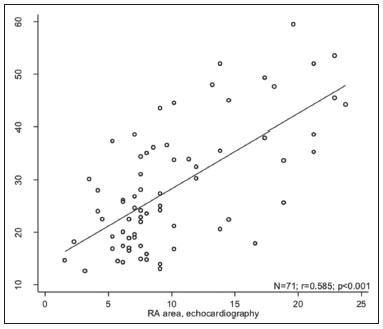

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease of the pulmonary vasculature that can involve multiple clinical conditions(1). It is defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥ 25 mmHg at rest and a pulmonary artery wedge pressure ≤ 15 mmHg, measured by right heart catheterization (RHC), as previously described(2). The clinical progression of the disease is characterized by impaired exercise tolerance, right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy, right-sided heart dilatation, and cardiac failure(3). Increasingly, researchers are looking for prognostic markers to assess risk in PAH(4). Recent studies have shown that the symptoms and outcomes of PAH are largely related to RV function(5). Echocardiography is currently the image modality most widely used in evaluating the structure and function of the RV(6). However, echocardiography is operator dependent and the image quality is often inadequate, especially for the RV(7). Therefore, evaluation of the RV ejection fraction (RVEF) through the use of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has emerged as the gold standard for the assessment of RV function(8). In many chronic diseases, such as PAH, risk assessment is essential to improve the management of cases(1,9). According to the European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society (ESC/ERS) pulmonary hypertension guidelines, risk should be assessed every 3–6 months and should involve multiple parameters, in order to evaluate disease progression and the response to treatment(1,10). As per the ESC/ERS guidelines, the only imaging parameter recommended routinely is the area of the right atrium (RA). However, assessment of the RVEF by cardiac MRI is known to have better prognostic value in PAH(11,12). Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the RA area and RVEF in comparison with other prognostic parameters in patients with PAH. MATERIALS AND METHODS Patients This was a retrospective study in which we identified 74 patients diagnosed with PAH by RHC at a referral center between January 2018 and May 2018. All of the patients underwent cardiac MRI within 3 months of the RHC, as well as undergoing echocardiography, a 6-minute walk test, and determination of the level of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) within a month of the RHC. Cardiac MRI protocol Cardiac MRI was performed in a 1.5 T scanner (Magnetom Aera; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). A half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo sequence was used, and the field-of-view (FOV) was patient adapted. The following sequence parameters were used: repetition time/ echo time (TR/TE), infinite/92 ms; flip angle, 150°; parallel acquisition factor, 2; slice thickness, 4 mm; distance factor, 20%; matrix, 380 × 256 (transverse plane) or 400 × 320 (coronal plane); and mean acquisition time, 90 s. The following measures were used for four-chamber and short-axis cine images: electrocardiogram-gated steady-state free-precession sequence; rate, 20 frames/cardiac cycle; slice thickness, 5 mm; FOV, 280–320 × 280–400 mm; matrix 256 × 256; bandwidth, 125 kHz/pixel; and TR/TE, 3.7/1.6 ms.The phase-contrast sequence was acquired orthogonal to the pulmonary artery trunk with a TR/TE of 5.6/2.7 ms, a slice thickness of 10 mm, an FOV of 280–320 × 280–400 mm, and a matrix of 256 × 128. Imaging analysis All cardiac MRI acquisitions were reviewed by two chest radiologists (with 8 and 10 years of experience in cardiac MRI, respectively) who were blinded to the RHC hemodynamic data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus; if a consensus could not be reached, a third radiologist (with 15 years of experience in cardiac MRI) made the final decision. The chest radiologist with 8 years of experience performed the right and left ventricular segmentation using specialized software (CardiacVX; GE Health-care, Waukesha, WI, USA), in accordance with the latest recommendations(13,14). The dimensions of the RA were measured at its maximum diameter in the four-chamber view (Figure 1A), whereas RV segmentation was performed in the short-axis view (Figure 1B).  Figure 1. Example of segmentation of the RV area at its maximum diameter in the four-chamber view (A) and in the short-axis view (B). Statistical analysis Data are presented as means ± standard deviations or as absolute and relative frequencies. We used chi-square tests to test associations between variables. For comparisons between continuous variables, Student’s t-tests or unequal variance t-tests were used. Pearson’s correlation coefficient or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used in order to assess linear associations between continuous variables. Coefficients were ranked as follows: 0.00–0.19, very weak; 0.20–0.39, weak; 0.40–0.69, moderate; 0.70–0.89, strong; and ≥ 0.90, very strong(15). Linear regression analysis was used in order to determine whether the demographic characteristics and interventional procedures affecting cardiac MRI were associated with the RA area and the RVEF. In all cases, values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Predictive Analytics Software package, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). RESULTS The characteristics of the study subjects are described in Table 1. Correlations between clinical characteristics and cardiac MRI findings are presented in Table 2. The area of the RA demonstrated a weak correlation with pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) measured by RHC (r = 0.268; p = 0.055) and a moderate correlation with the NT-proBNP level (r = 0.429; p = 0.003). The RVEF showed statistically significant correlations with all of the clinical characteristics evaluated (Table 2). The RA area determined by MRI demonstrated a moderate correlation with that determined by echocardiography (r = 0.585; p < 0.001), as shown in Figure 2.    Figure 2. Correlation between the RA area quantified by MRI and that quantified by echocardiography (r = 0.585; p < 0.001). In the univariate linear analysis, the RA area correlated significantly with PVR, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), and the NT-proBNP level, as did the RVEF (Table 3). However, the RVEF also correlated significantly with age, functional class, and cardiac output. DISCUSSION Recent studies have highlighted the importance of imaging methods in the evaluation of cardiac diseases(16–21). The present study compared the RVEF and RA area, as assessed by cardiac MRI, with other known prognostic markers in PAH. Our findings indicate that the RVEF and the RA area both have a relationship with the clinical prognosis. However, the RVEF showed more significant correlations and stronger associations with prognostic factors than did the RA area. Many previous studies have attempted to identify biomarkers capable of predicting risk in patients with PAH. Such markers allow physicians to monitor disease progression, to determine the prognosis, and to assess responses to treatment in patients with PAH(9). Regular risk assessment is essential in such patients(1). According to the 2015 ESC/ERS pulmonary hypertension guidelines, the evaluation of multiple variables can be used in order to categorize patients with PAH as being at low, intermediate, or high risk(1). In the ESC/ERS guidelines, one of the observed parameters for risk assessment is the RA area(1). The size of the RA has demonstrated prognostic value in PAH(22,23). Querejeta Roca et al.(24) found no correlation between RA function and hemodynamic parameters. Our findings corroborate the hypothesis that changes in the RA can manifest very late, after the RV has already failed. In one study, the size of the RA, as determined by echocardiography, was shown to be an independent prognostic factor in patients with pulmonary hypertension(25). In another study, RA size was found to be associated with a decrease in survival in patients with PAH(26). Nevertheless, both of those studies measured the area of the RA by echo-cardiography, which is less accurate than is cardiac MRI. Nevertheless, our study demonstrated that the RVEF is a better prognostic factor than is the RA area in comparison with other biomarkers, such as TAPSE, the NT-proBNP level, and the total 6-minute walk distance. In patients with PAH, RV function is an important predictor of survival(13,14). Cardiac MRI is the gold-standard imaging modality for the evaluation of RV function, including the RVEF(27), which is an established prognostic factor in patients with PAH(12,28). In the present study, there was no significant association between the RVEF and mortality, likely due to the small number of events in the follow-up period. Our study has some limitations. First, because of the retrospective nature of the study, all of the participants had previously been diagnosed with PAH, which constitutes a selection bias. Second, this was a preliminary study and involved a small number of participants. Further studies involving larger samples are needed in order to validate the results presented here. Therefore, prospective studies are warranted in order to elucidate the potential of cardiac MRI to diagnose patients referred for investigation of suspected pulmonary hypertension. CONCLUSION Our study showed that the RVEF and the RA area were both associated with prognostic factors in patients with PAH. However, the RVEF showed more significant correlations and stronger associations with prognostic factors than did the RA area. REFERENCES 1. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:67–119. 2. Sommer N, Richter MJ, Tello K, et al. Update pulmonary arterial hypertension: definitions, diagnosis, therapy. Internist (Berl). 2017;58:937–57. 3. Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation. 2010;122:164–72. 4. Dawes TJW, de Marvao A, Shi W, et al. Machine learning of threedimensional right ventricular motion enables outcome prediction in pulmonary hypertension: a cardiac MR imaging study. Radiology. 2017;283:381–90. 5. Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, et al. Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D22–33. 6. Siqueira ME, Pozo E, Fernandes VR, et al. Characterization and clinical significance of right ventricular mechanics in pulmonary hypertension evaluated with cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature tracking. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:39. 7. Haddad F, Hunt SA, Rosenthal DN, et al. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part I: anatomy, physiology, aging, and functional assessment of the right ventricle. Circulation. 2008;117:1436–48. 8. Spruijt OA, Di Pasqua MC, Bogaard HJ, et al. Serial assessment of right ventricular systolic function in patients with precapillary pulmonary hypertension using simple echocardiographic parameters: a comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiol. 2017;69:182–8. 9. Raina A, Humbert M. Risk assessment in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25:390–8. 10. McLaughlin VV, Gaine SP, Howard LS, et al. Treatment goals of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl): D73–81. 11. Peacock AJ, Crawley S, McLure L, et al. Changes in right ventricular function measured by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients receiving pulmonary arterial hypertension-targeted therapy: the EURO-MR study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:107–14. 12. van de Veerdonk MC, Kind T, Marcus JT, et al. Progressive right ventricular dysfunction in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension responding to therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2511–9. 13. Schulz-Menger J, Bluemke DA, Bremerich J, et al. Standardized image interpretation and post processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance: Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) board of trustees task force on standardized post processing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:35. 14. Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34–41. 15. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1: 307–10. 16. Albuquerque KS, Indiani JMC, Martin MF, et al. Asymptomatic apical aneurysm of the left ventricle with intracavitary thrombus: a diagnosis missed by echocardiography. Radiol Bras. 2018;51:275–6. 17. Pelandré GL, Sanches NMP, Nacif MS, et ali E. Detection of coronary artery calcification with nontriggered computed tomography of the chest. Radiol Bras. 2018;51:8–12. 18. Niemeyer R, Niemeyer B, Martins WA, et al. Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum. Radiol Bras. 2018;51:130–2. 19. Nacif MS, Raman FS, Gai N, et al. Myocardial T1 mapping and determination of partition coefficients at 3 tesla: comparison between gadobenate dimeglumine and gadofosveset trisodium. Radiol Bras. 2018;51:13–9. 20. Oliveira DCL, Pacheco EO, Lopes LTR, et al. Pericardial synovial sarcoma: radiological findings. Radiol Bras. 2018;51:201–2. 21. Neves PO, Andrade J, Monção H. Coronary artery calcium score: current status. Radiol Bras. 2017;50:182–9. 22. Cogswell R, Pritzker M, De Marco T. Performance of the REVEAL pulmonary arterial hypertension prediction model using non-invasive and routinely measured parameters. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:382–7. 23. D’Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:343–9. 24. Querejeta Roca G, Campbell P, Claggett B, et al. Right atrial function in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e003521. 25. Bustamante-Labarta M, Perrone S, De La Fuente RL, et al. Right atrial size and tricuspid regurgitation severity predict mortality or transplantation in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15(10 Pt 2):1160–4. 26. Austin C, Alassas K, Burger C, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of estimated right atrial pressure and size predicts mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2015;147:198–208. 27. Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Souza R. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: what can it add to our knowledge of the right ventricle in pulmonary arterial hypertension? Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(6 Suppl):25S–31S. 28. van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, et al. Prognostic value of right ventricular mass, volume, and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1250–7. 1. Pulmonary Hypertension Group, Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil 2. Medical Imaging Research Laboratory, Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil 3. School of Medicine, Graduate Program in Medicine and Health Sciences, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil 4. Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil a. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2702-6732 b. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6948-3982 c. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9214-1916 d. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3733-5707 e. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1715-831X f. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3125-1385 g. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9425-7872 h. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8797-7380 i. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1984-4636 Correspondence: Dr. Marcelo M. Mello Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre Avenida Independência, 75, Independência Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, 90035-074 Email: marcelommello@outlook.com Received 15 November 2018 Accepted after revision 7 May 2019 |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554