Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 51 nº 1 - Jan. /Feb. of 2018

Vol. 51 nº 1 - Jan. /Feb. of 2018

|

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

|

|

Pulmonary cryptococcosis mimicking neoplasm in terms of uptake PET/CT |

|

|

Autho(rs): Lucas de Pádua Gomes de Farias1; Igor Gomes Padilha1; Márcia Rosana Leite Lemos2; Carla Jotta Justo dos Santos2; Christiana Maria Nobre Rocha de Miranda2 |

|

|

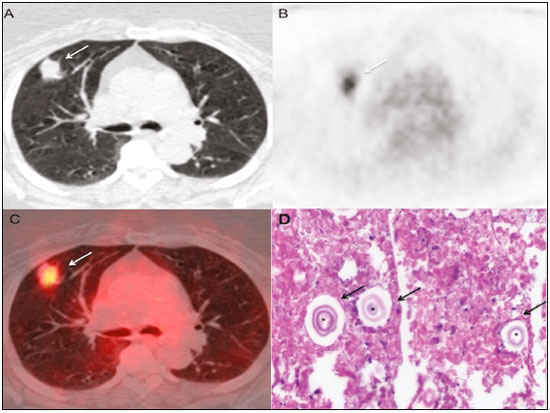

Dear Editor,

We report the case of a 64-year-old female nonsmoker who presented with complaints of chronic cough and weight loss. Physical examination revealed no fever or other abnormalities. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) demonstrated a mass, with soft tissue attenuation and spiculated borders, in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe, arising from the horizontal fissure and extending to the pleura, measuring 3.2 × 2.2 × 1.2 cm, with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUV) of 5.5 and high glycolytic metabolism (Figure 1A–C). The patient underwent lung biopsy, and histopathological analysis of the biopsy sample indicated cryptococcosis (Figure 1D).  Figure 1. A–C: PET/CT scans showing a spiculated mass with soft tissue attenuation, located in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe, arising from the horizontal fissure and extending to the pleura (arrows), with a maximum SUV of 5.5. D: Histological slide, with hematoxylin-eosin staining (magnification, ×10), of a lung biopsy sample, showing rounded structures with basophilic capsules (asterisks), accompanied by nuclear fragmentation of inflammatory cells, together with macrophages and multinucleated giant cells (arrows). Histochemical analysis, with mucicarmine and Grocott’s staining, confirmed the presence of cryptococci. Pulmonary cryptococcosis is caused by fungi of the genus Cryptococcus (C. neoformans and C. gattii), which are monomorphic encapsulated yeasts that are found worldwide, particularly in soil contaminated with pigeon droppings and decomposing wood. Although infection occurs through the inhalation of airborne infectious particles, pneumonia is relatively uncommon in infected individuals. In fact, after hematogenous dissemination, infection of the central nervous system is more common than is pneumonia(1–4). Pulmonary cryptococcosis has a variety of clinical and pathological presentations. It can manifest in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, although the latter account for the majority of cases, with a wide variety of radiological abnormalities. The following are the main characteristics to be identified by CT(2–4): location and distribution; solitary or multiple nodules that can progress to confluence or cavitation; segmental consolidation or infiltrative masses; hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement; pleural effusion; reticular or nodular infiltrate; linear opacities; septal thickening; and endobronchial lesions. The diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis is difficult to make, because the organisms often colonize the upper airways and the symptoms are nonspecific, as are the radiological manifestations(4). In the diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis, PET/CT plays a complementary role. In approximately 60% of patients, cryptococcal lesions show 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake that is greater than is that of the mediastinal blood pool. The SUV, a calculated measure of contrast uptake, is used in order to identify the underlying cause of such lesions, knowledge of their physiological distributions and variants being of fundamental importance for minimizing errors of interpretation(1,5,6). Typically, low SUVs (≤ 2.5) are associated with benign lesions, whereas high SUVs (> 2.5) are associated with malignant lesions(1,5). Sharma et al.(1) demonstrated that the SUVs of cryptococcal lesions range from 0.93 to 11.6. When PET/CT is used in order to differentiate pulmonary nodules and to discriminate between infection and malignancy, its potential pitfalls should be borne in mind, especially in areas where the prevalence of granulomatous infection is high, as well as in immunocompromised patients(7,8). Inflammatory and infectious lesions can show elevated metabolic rates and can therefore be misidentified as malignant lesions(5,6,8), thus posing a diagnostic challenge(6). In patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis, there is great variability in the SUVs of cryptococcal lesions. Therefore, the clinical correlation, risk factors for cancer development, and geographic location, together with the PET/CT findings, are fundamental for diagnostic clarification, although it is usually necessary to perform a lung biopsy(1,5,8). REFERENCES 1. Sharma P, Mukherjee A, Karunanithi S, et al. Potential role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with fungal infections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:180–9. 2. Lindell RM, Hartman TE, Nadrous HF, et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: CT findings in immunocompetent patients. Radiology. 2005;236:326–31. 3. Fox DL, Müller NL. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients: CT findings in 12 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:622–6. 4. Lee WY, Wu JT, Jeng CM, et al. CT findings of pulmonary cryptococcosis: a series of 12 cases. Chin J Radiol. 2005;30:319–25. 5, Truong MT, Ko JP, Rossi SE, et al. Update in the evaluation of the solitary pulmonary nodule. Radiographics. 2014;34:1658–79. 6. Mosmann MP, Borba MA, Macedo FPN, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodule and 18F-FDG PET/CT. Part 1: epidemiology, morphological evaluation and cancer probability. Radiol Bras. 2016;49:35–42. 7. Hsu CH, Lee CM, Wang FC, et al. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in pulmonary cryptococcoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28:791–3. 8. Deppen S, Putnam JB Jr, Andrade G, et al. Accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer in a region of endemic granulomatous disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:428–32. 1. Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL), Maceió, AL, Brazil 2. Clínica de Medicina Nuclear e Radiologia de Maceió (MedRadius), Maceió, AL, Brazil Mailing address: Dra. Christiana Maria Nobre Rocha de Miranda Clínica de Medicina Nuclear e Radiologia de Maceió (MedRadius) Rua Hugo Corrêa Paes, 104, Farol Maceió, AL, Brazil, 57050-730 E-mail: maia.christiana@gmail.com |

|

GN1© Copyright 2025 - All rights reserved to Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia e Diagnóstico por Imagem

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554