Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 47 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2014

Vol. 47 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2014

|

ICONOGRAPHIC ESSAY

|

|

Uncommon hepatic tumors: iconographic essay - Part 1 |

|

|

Autho(rs): Bruno Cheregati Pedrassa1; Eduardo Lima da Rocha1; Marcelo Longo Kierszenbaum1; Renata Lilian Bormann1; Lucas Rios Torres2; Giuseppe D'Ippolito3 |

|

|

Keywords: Neoplasms; Liver; Atypical; Computed tomography; Magnetic resonance imaging. |

|

|

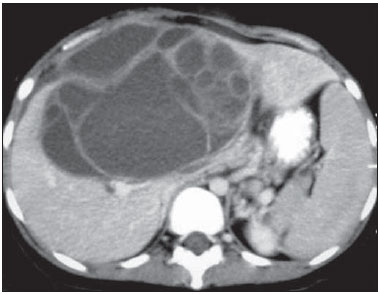

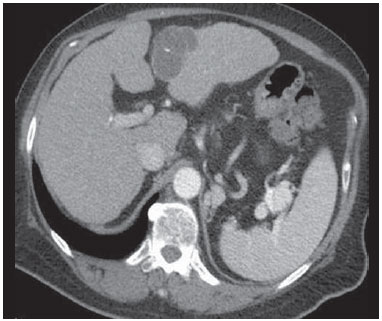

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

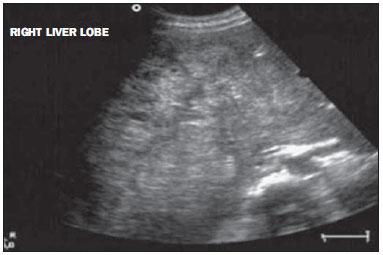

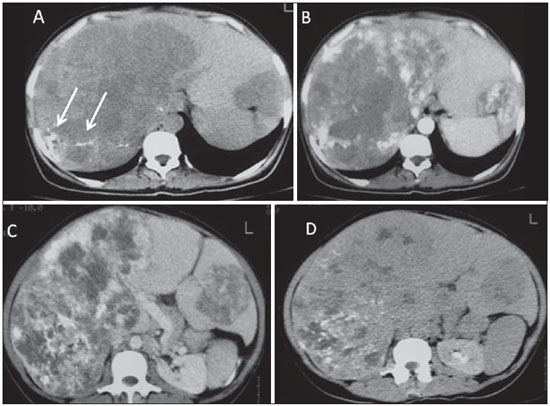

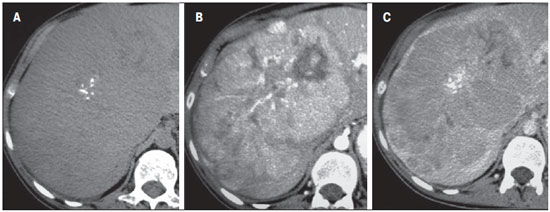

A wide range of tumors affect the liver, and 90% of the focal liver lesions are benign. Among benign liver tumors, hemangiomas and focal nodular hyperplasias are the most common non-cystic lesions(1). Metastases are the most frequently found malignant neoplasms; hepatocellular carcinomas being responsible for 80-85% of primary malignant tumors, followed by intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas(2). The diagnosis of typical liver lesions can be safely made with different imaging methods; by contrast, uncommon lesions generally represent a diagnostic challenge for radiologists. Among tumors considered uncommon, one highlights epithelial tumors such as cystadenomas and biliary cystadenocarcinomas, non epithelial tumors including angiomyolipomas, epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas and angiosarcomas, besides other such as lymphomas, inflammatory pseudotumors (myofibroblastic tumors) and some sarcomas(3). Few studies are available in the literature providing a comparative and comprehensive analysis of imaging findings of uncommon liver tumors. The objective of this study is, by means of a pictorial essay, to describe the main imaging findings of several uncommon benign and malignant liver tumors observed at computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance magnetic (MRI). ANGIOSARCOMA It is the most common primary liver sarcoma, representing 2% of the malignant hepatic neoplasms, frequently affecting patients in the sixth and seventh decades of life, with prevalence in men (4 men:1 woman)(4). Patients with liver angiosarcoma present a poor prognosis. At the moment of the diagnosis, most of them have metastatic lesions, generally in the lungs and spleen (60% of cases), and a mean survival of six months(5). The development of such tumors is associated with exposure to chemical substances such as thorium dioxide, vinyl chloride and arsenic and, in some cases is related to hemochromatosis and use of anabolic steroids(5,6). The pathological evaluation of angiosarcomas may demonstrate four growth patterns, as follows: multiple nodules; dominant mass; mixed pattern (dominant mass with nodules); and diffuse micronodular infiltration. Among such patterns, the multinodular and the diffuse micronodular infiltration patterns are most commonly observed(4). Imaging findings vary, which reflects the diverse histological composition of the lesions(7). At ultrasonography (US), one may observe a heterogeneous mass (Figure 1), eventually with hyperechogenic areas with posterior acoustic shadowing, indicating the presence of calcifications(8). At CT, most lesions are hypodense at the non contrast-enhanced phase, but some of them may be hyperattenuating due to the presence of areas of intralesional bleeding. After intravenous contrast injection, at the arterial and portal phases, they may present focal areas of central and ring-shaped heterogeneous enhancement persistent and progressive at delayed phases, in addition to possible calcifications(4) (Figure 2). Recent studies have demonstrated that angiosarcomas do not present the same progressive centripetal enhancement of cavernous hemangiomas, differently from descriptions in earlier studies, so both entities can be safely differentiated by imaging methods(4,5).  Figure 1. Angiosarcoma. Ultrasonography demonstrates the presence of a predominantly hyperechogenic, heterogeneous hepatic mass occupying the whole right liver lobe.  Figure 2. Angiosarcoma. Abdominal CT. At the non-contrast-enhanced phase, the presence of hypodense and heterogeneous liver masses is identified, intermingled with foci of calcifications. The largest of such masses occupies the whole right liver lobe (A). At the arterial phase, the mass presents intense enhancement by the iodinated contrast agent, representing hypervascularization (B), which remains at the portal (C) and delayed (D) phases. At MRI, such tumors may demonstrate areas with hypersignal on T1-weighted sequences, and heterogeneous aspect on T2-weighted sequences, with foci of hemorrhage, fibrotic septa or intermixed calcifications, presenting early and progressive enhancement(5). Main differential diagnoses include epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hypervascular metastasis(4). Main aspects favoring the diagnosis of hepatic angiosarcoma include:

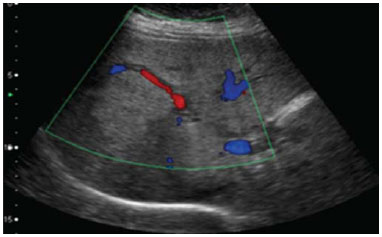

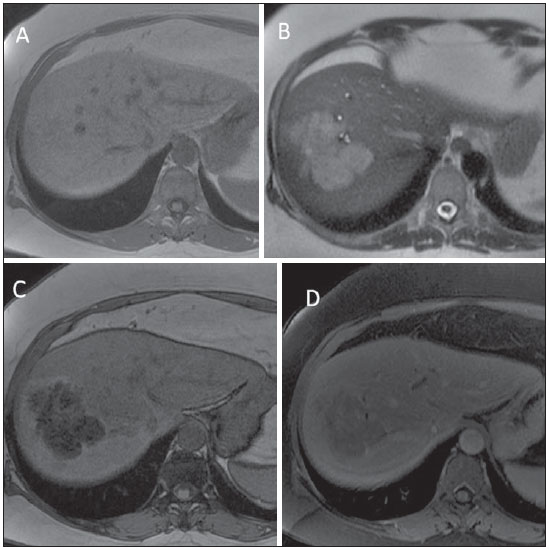

ANGIOMYOLIPOMA Angiomyolipoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor with varied histological components such as fat tissue, smooth muscle and vessels(7). Recent studies suggest that angiomyolipoma is not a mesenchymal lesion, but a neoplasia originating from perivascular epithelioid cells, classified by the World Health Organization as PEComa ("perivascular epithelioid cells" tumor)(8). It occurs more frequently in middle aged women and 50% of patients are asymptomatic. Symptoms are observed in cases where intralesional bleeding is present, which generally occurs in lesions > 5.0 cm. There is neither association with tuberous sclerosis nor with renal angiomyolipomas. Most patients do not present hepatopathy and tumor markers (CEA and CA 19-9) are negative(7,8). Due to the presence of different histological components, hepatic angiomyolipoma presents variable imaging features, many times resembling those of hepatocarcinoma. The diagnosis is preoperatively suspected in only 11% to 25% of cases, respectively by CT and MRI(9). At US, the lesion may appear hyperechogenic and homogeneous, similar to hemangioma (Figure 3). At CT and MRI, in the presence of a sufficient amount of intralesional fat, one can identify it with basis on the negative CT density and signal drop on out-of-phase gradient-echo sequence (Figure 4). Main differential diagnoses include fatty liver lesions such as adenoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, lipoma and liposarcoma(9).  Figure 3. Angiomyolipoma. Ultrasonography demonstrates the presence of hyperechogenic liver mass with lobulated contours and central flow at Doppler, located in the segments VII/VIII.  Figure 4. Angiomyolipoma. At abdominal MRI, the lesion presents subtle hypersignal on T1-weighted (A) and non homogeneous hypersignal on T2-weighted (B) sequences. At the out-ofphase sequence, marked signal dropout is observed, indicating fat component (C). After paramagnetic contrast injection, atypical enhancement is observed (D). Main aspects to be considered in the diagnosis of angiomyolipomas include:

CYSTADENOMA AND BILIARY CYSTADENOCARCINOMA Biliary cystadenomas are uncommon and represent less than 5% of all uni- or multilocular cysts of biliary origin(10). Generally, most of these lesions are intrahepatic (85% of cases), with diameter ranging from 1.5 cm to 35 cm and predilection for the right liver lobe(9). Predominantly, such lesions affect middle aged women and in less than 5% of cases are considered to be pre-malignant lesions(11). Symptoms, if present, are associated with mass-effect and consist in intermittent pain or jaundice(12). Macroscopically, the lesion is cystic, with fluid or mucinous content. Hemorrhagic, biliary, mixed and even purulent content may be found. At histological analysis, the epithelium shows papillary projections or polyps, besides ovarian stromal cells in female patients(9). At CT and MRI, such lesions present as a solitary cystic mass with a well defined fibrous capsule, mural nodules, internal septa, calcifications and fluid-fluid level(9) (Figures 5 and 6).  Figure 5. A 42-year-old female patient with no previous history of disease, complaining of a painful, palpable mass in the epigastrium. Contrast-enhanced CT portal phase demonstrates cystic multiloculated lesion, with thick internal septa enhanced after contrast injection. The diagnosis was biliary cystadenocarcinoma.  Figure 6. Biliary cystadenoma. Contrast-enhanced CT portal phase demonstrates cystic lesion with fine internal septa intermingled with foci of calcification. Main differential diagnoses include hydatid cyst, cystic metastasis and abscess(9). Main aspects to be considered in the diagnosis of biliary cystadenoma include:

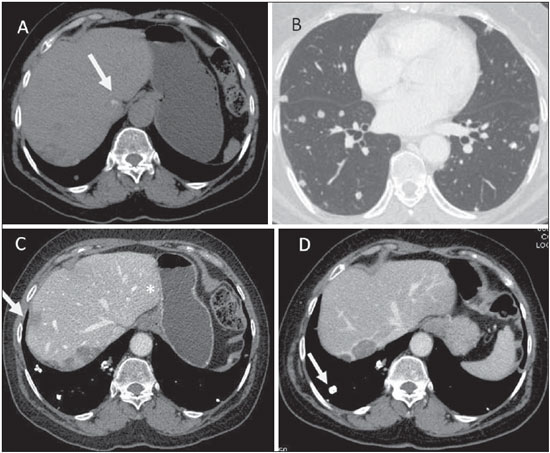

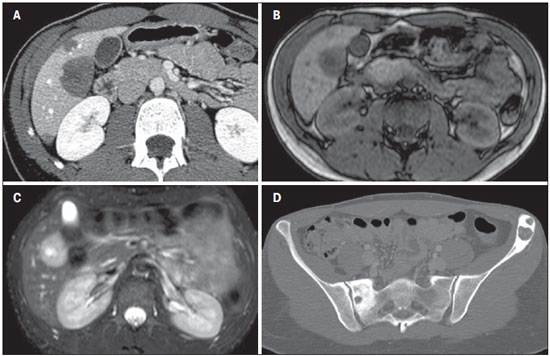

EPITHELIOID HEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA It is a malignant tumor of vascular origin affecting adult individuals, particularly women since estrogen is an associated risk factor. It is considered an insidious neoplasm of intermediate to low grade malignancy and, on average, a five-year survival rate is about 50%(13,14). Clinical findings are nonspecific and include right hypochondrium pain and weight loss, and in some cases may progress with fulminant hepatitis or Budd-Chiari syndrome(13). Most common metastasis sites include abdominal lymph nodes, peritoneum, lungs and bones(14). Epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas have the following imaging presentations: nodular and diffuse. The multinodular presentation represents the initial phase of the disease, when frequently subcapsular nodules with varied sizes and peripheral distribution are found. On the other hand, in late phases, the nodules grow and coalesce, forming extensive and infiltrative lesions(6). After intravenous contrast injection, the lesions may present peripheral and central enhancement, corresponding to capsular retraction and calcifications within the lesion can be noted (Figure 7). Alomari have described the so called "lollipop sign" that can be observed at CT and MRI, corresponding to abrupt termination of the portal vein or hepatic artery in the mass periphery and representing a specific finding of this entity(15).  Figure 7. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Non-contrast-enhanced abdominal CT identifies the presence of hypodense peripheral hepatic nodules intermingled with foci of calcifications (arrow on A), which may occur in up to 25% of cases. Chest CT of the same patient (B) demonstrates the presence of sparse secondary nodules randomly distributed on the pulmonary parenchyma. At abdominal CT portal phase (C,D) hepatic nodules present with more intense enhancement in the periphery of the lesion, hepatic capsule retraction (arrow on C), besides calcified lung metastases (arrow on D). Pulmonary metastases generally calcify and bone metastases are osteolytic, insufflating and with marginal sclerosis (Figures 7 and 8).  Figure 8. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. A: Abdominal CT portal phase demonstrates the presence of hypovascular peripheral hepatic nodules. MRI demonstrates that the hepatic nodule presents low signal intensity at T1-weighted sequences (B) and high signal intensity at T2-weighted with target sign (C). At pelvic CT, insufflating osteolytic lesions are observed, with marginal sclerosis in the left iliac bone and scrum at right (D). Main aspects to be considered in the diagnosis of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma include:

FIBROLAMELLAR HEPATOCARCINOMA It is a primary malignant tumor corresponding to 1-9% of all tumors of hepatocellular origin. Clinical, laboratory, histopathological and imaging findings differentiate this tumor from the conventional hepatocellular carcinoma. It occurs preferentially in adolescent patients or in young adults with neither underlying hepatopathy nor increasing in tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein(16). Almost all cases are incidentally diagnosed at late stages of the disease, since it is asymptomatic. However, pain, palpable abdominal mass and ascites are most commonly observed in symptomatic cases (40% of cases)(16). Frequent CT and MRI findings of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas include large solitary lobulated and well defined mass (80% of cases) in non cirrhotic liver which, in 50% of the cases cause biliary tract dilatation. After intravenous contrast agent injection, such lesions present heterogeneous hypervascular enhancement, with radiating septa and central scar (70% of cases) with a fibrotic component that presents delayed enhancement, which is helpful to differentiate this tumor from focal nodular hyperplasia. Metastasis occurs in 30% of cases, most frequently in lungs and adrenal glands(17). Calcifications are found in about 50% of cases investigated by CT and almost exclusively in the region of the central scar, differently from focal nodular hyperplasia where calcifications are extremely rare(17) (Figure 9).  Figure 9. A 23-year-old woman with no hepatopathy and negative tumor markers and with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Non-contrast-enhanced CT (A) arterial (B) and equilibrium (C) phases demonstrate the presence of a subtly hypodense large mass in the right liver lobe, with central punctiform calcifications presenting heterogeneous hypervascular enhancement with progressive appearance in its central region, intermingled with necrotic areas. Main aspects to be considered in the diagnosis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma include:

CONCLUSION Radiological findings of the most common liver lesions are well known and widely described in the literature. On the other hand, scarce studies are found in the literature consolidating the main information regarding more rare liver tumors and lesions(18-22). In this first part of the present study, the authors describe the main clinical-radiological characteristics of these rare tumors. Although in the great majority of cases, the definitive diagnosis must be confirmed by histopathological analysis, the imaging findings can raise the diagnostic suspicion, hence the relevance of familiarity with such radiological findings to reduce the list of differential diagnoses and increase the chances for a more accurate radiological evaluation. REFERENCES 1. Tiferes DA, D'Ippolito G. Neoplasias hepáticas: caracterização por métodos de imagem. Radiol Bras. 2008;41:119-27. 2. Walther Z, Jain D. Molecular pathology of hepatic neoplasms: classification and clinical significance. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:403929. 3. Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000. 4. Yu RS, Chen Y, Jiang B, et al. Primary hepatic sarcomas: CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2196-205. 5. Koyama T, Fletcher JG, Johnson CD, et al. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma: findings at CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 2002;222:667-73. 6. Kim KA, Kim KW, Park SH, et al. Unusual mesenchymal liver tumors in adults: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W481-9. 7. Zhou YM, Li B, Xu F, et al. Clinical features of hepatic angiomyolipoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:284-7. 8. Chang Z, Zhang JM, Ying JQ, et al. Characteristics and treatment strategy of hepatic angiomyolipoma: a series of 94 patients collected from four institutions. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2011;20:65-9. 9. Mortelé KJ, Ros PR. Cystic focal liver lesions in the adult: differential CT and MR imaging features. Radiographics. 2001;21:895-910. 10. Billington PD, Prescott RJ, Lapsia S. Diagnosis of a biliary cystadenoma demonstrating communication with the biliary system by MRI using a hepatocyte-specific contrast agent. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e35-6. 11. Tsepelaki A, Kirkilesis I, Katsiva V, et al. Biliary cystadenoma of the liver: case report and systematic review of the literature. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2009;22:278-83. 12. Lewin M, Mourra N, Honigman I, et al. Assessment of MRI and MRCP in diagnosis of biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:407-13. 13. Lyburn ID, Torreggiani WC, Harris AC, et al. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: sonographic, CT, and MR imaging appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1359-64. 14. Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG, Goodman ZD. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic study of 137 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:562-82. 15. Alomari AI. The lollipop sign: a new cross-sectional sign of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:460-4. 16. Ichikawa T, Federle MP, Grazioli L, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: pre- and posttherapy evaluation with CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;217:145-51. 17. Ichikawa T, Federle MP, Grazioli L, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213:352-61. 18. Gossling PAM, Alves GRT, Silva RVA, et al. Bilioma espontâneo: relato de caso e revisão da literatura. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:59-60. 19. Guimarães Filho A, Carneiro Neto LA, Palhtea MS, et al. Doença de Caroli complicada com abscesso hepático: relato de caso. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:362-4. 20. Hollanda ES, Torres US, Gual F, et al. Perfuração espontânea da vesícula biliar com formação de biloma intra-hepático: sinais ultrassonográficos e correlação com tomografia computadorizada. Radiol Bras. 2013;46:320-2. 21. Galvão BVT, Torres LR, Cardia PP, et al. Prevalência de cistos simples e hemangiomas hepáticos em pacientes cirróticos e não cirróticos submetidos a exames de ressonância magnética. Radiol Bras. 2013;46:203-8. 22. Torres LR, Timbó LS, Ribeiro CMF, et al. Hemangioendotelioma hepático multifocal e metastático: relato de caso e revisão da literatura. Radiol Bras. 2014;47:194-6. 1. MDs, Radiologists, Trainees at the Unit of Abdomen, Department of Imaging Diagnosis - Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil 2. Master, Fellow PhD degree, Department of Imaging Diagnosis - Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), MD, Radiologist, Hospital São Luiz, São Paulo, SP, Brazil 3. Private Docent, Professor, Department of Imaging Diagnosis - Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Mailing Address: Dr. Giuseppe D'Ippolito Departamento de Diagnóstico por Imagem - EPM-Unifesp Rua Napoleão de Barros, 800, Vila Clementino São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 04024-012 E-mail: giuseppe_dr@uol.br Received March 28, 2013. Accepted after revision October 14, 2013. Study developed at Department of Imaging Diagnosis - Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil. |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554