Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 46 nº 3 - May / June of 2013

Vol. 46 nº 3 - May / June of 2013

|

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

|

|

Performance of diagnostic centers in the classification of opportunistic screening mammograms from the Brazilian public health system (SUS) |

|

|

Autho(rs): Danielle Cristina Netto Rodrigues1; Ruffo Freitas-Junior2; Rosangela da Silveira Corrêa3; João Emílio Peixoto4; Jeane Gláucia Tomazelli5; Rosemar Macedo Sousa Rahal6 |

|

|

Keywords: Breast cancer; Screening programs; Mammography; Information systems; Health services. |

|

|

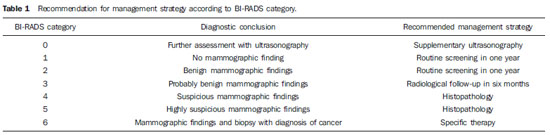

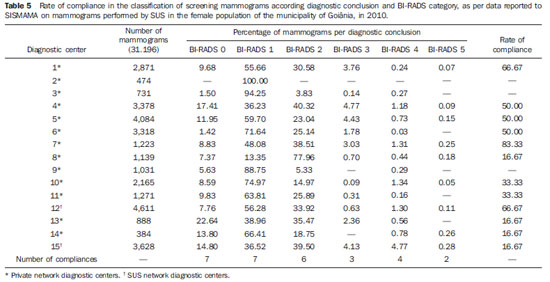

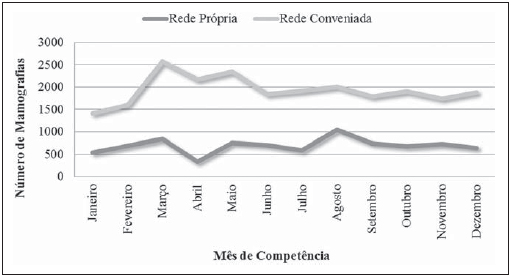

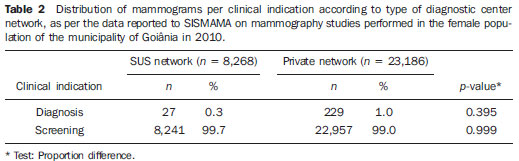

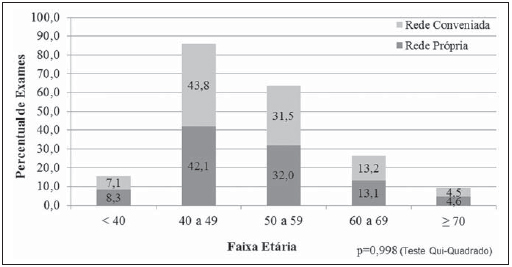

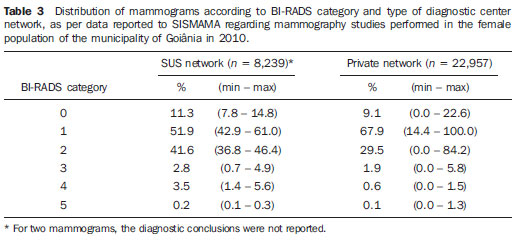

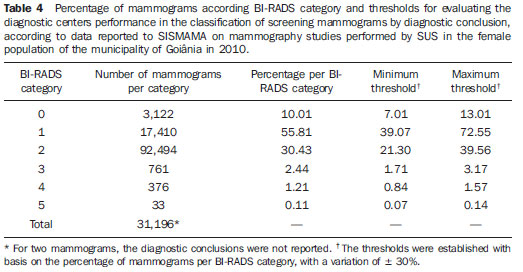

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

Currently, two models of mammographic screening are utilized for early detection of breast cancer, as follows: an organized screening program where there is an active planning for pre-established age groups invited to undergo screening mammography on a pre-established periodicity; and an opportunistic screening program to meet a spontaneous demand(1–4). In Brazil, despite investments and improvements in health efforts, with breast cancer management being one of the priorities in health policies, what one actually observes is an opportunistic mammographic screening limited by logistical and economic factors as well as by socio-cultural barriers(5–10). A study undertaken in the city of Taubaté, São Paulo State, Brazil, demonstrates such situation, as a substantial proportion of women is not screened or does not comply with received recommendations. Many of the women fail or delay to attend the ensuing screening steps(1). The recommendations for breast cancer screening in Brazil were consensually defined and published in April 2004 by Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA) with the title "Controle do câncer da mama – Documento de consenso" (Breast Cancer Management – Consensus Document)(11). Such document, in association with other government actions, demonstrates changes in the strategies for management and prevention of breast cancer in Brazil(11). In order to guide strategies governing the Consensus Document(11) and meet the need for implementation of management tools to evaluate the performance of Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS)(12,13), a breast cancer management system (Sistema de Informação do Controle do Câncer de Mama – SISMAMA) was implemented to provide computerized data on procedures performed in health centers for screening and diagnostic confirmation of breast cancer(14). And in order to improve the quality of data for monitoring and assessment of the National Program for Breast Cancer Management, it is necessary to implement results audits at each breast diagnostic center, and such centers must also have the quality assurance instruments, both for the imaging procedure as well as for the forwarding of data(14). With such purpose in view, and based on the Brazilian Ministry of Health Ordinance No. 531 dated March 26, 2012 establishing the method for calculating the indicators utilized for monitoring mammographic studies results in the breast cancer screening, the Programa Nacional de Qualidade em Mamografia – PNQM (National Program for Quality in Mammography) was instituted along with the Quality Requirements for Mammographic Studies and Reports applicable to imaging diagnostic centers performing mammography in the whole Brazilian country(15). Thus, considering the scarcity of studies on opportunistic mammographic screening for breast cancer, particularly those studies performed by SUS, besides the need for data on the audits performed at breast diagnostic centers for SUS, the present study was aimed at evaluating the performance of the diagnostic centers in the classification of mammographic reports in opportunistic screening performed in 2010 by SUS in the city of Goiânia, state of Goiás, and also at describing the production of imaging studies on a monthly basis, clinical indication, age group and diagnostic conclusion, according to the type of network the diagnostic centers belong to. MATERIALS AND METHODS The present ecological study analyzed data reported to the SISMAMA by diagnostic centers involved in the mammographic screening developed by the SUS in the period from January to December 2010, involving the female population of the city of Goiânia, state of Goiás, Brazil. Such study is part of the investigation named "Sistema de informação, monitoramento e emissão de laudo em mamografia" (System of information, monitoring and data reporting in mammography) approved by the Committee for Ethics in Research Dr. Henrique Santillo, State of Goiás Secretary of Health, without the need for a term of free and informed consent. Study area The area covered by the analysis in the present study was the municipality of Goiânia, capital city of the state of Goiás, located in the Mid-western region of the country. The municipality comprises an area of approximately 732,801 km2 and a population of 1,302,001 inhabitants, with 681,144 being women(16). Data acquisition and processing According to the SISMAMA operational flow(17), the data were acquired from the "data export" file of the state coordination module, based on the period from January to December 2010. From the "General Routines" menu of SISMAMA, the files were imported, and from then on, databases were generated and the variables were tabulated with the TabWin tool(18). The frequencies for the following variables were calculated: mammograms production per diagnostic center (service provider); monthly mammograms production; mammograms per clinical indication (screening or diagnosis); screening mammograms per age group (< 40 years; 40 to 49 years, 60 to 69 years and > 70 years); and screening mammograms per diagnostic conclusion. The radiological classification at SISMAMA followed the classification proposed by the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) published by the American College of Radiology (ACR) and translated into Portuguese by Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia and Imaging Diagnosis (CBR). Such a system utilizes categories from zero to six in the description of imaging findings and provides approach recommendations for each category, with the purpose of minimizing the differences inherent to intraobserver variability or disagreement, as described on Table 1(19–21). The diagnostic centers were classified into two types of networks: the SUS network and the service providers network. The SUS network comprises public services, while the services providers network comprises philanthropic and private services accredited by SUS for rendering mammography services. Performance evaluation Initially, the performance was evaluated according to the compliance of each diagnostic center with the BI-RADS in the classification of mammographic reports. Taking into consideration the absence of data in the literature regarding the frequency of mammograms per BI-RADS category in the mammographic screening performed by SUS in the city of Goiânia, an arbitrary variation threshold of ± 30% of the relative frequency presented by all diagnostic centers for each BI-RADS category was established to evaluate the diagnostic centers conformity. The centers that were within such threshold were considered as being compliant. The calculation of the conformity score for each diagnostic center was based on the established threshold. A score 1 was attributed for compliance and score zero was attributed for non-compliance, for each BI-RADS category. Thus, for the six BI-RADS categories (0 thru 5), the total score for each diagnostic center ranged from zero to six. Based on the score for each diagnostic center, the respective rate of compliance was calculated. Later, by means of the rate of compliance, the equality in the diagnostic centers performance was evaluated. For such a purpose, one considered centers with equal performance those with equal rates of compliance. Data analysis For the statistical data analysis, the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 17.0 (SPSS) (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA) software was utilized, and the absolute and relative frequencies of the variables were calculated. RESULTS According to the data reported to SISMAMA, 15 diagnostic centers performed mammography for SUS in the city of Goiânia in the year of 2010. Of those centers, two were public services belonging to SUS and 13 were private service providers. Such 15 centers reported to SISMAMA the information on 36,253 mammograms performed in 2010. According to place of residence, 31,474 (86.8%) mammography was performed in individuals living in cedures being performed in women and 20 (0.1%) in men. Of the 31,454 mammograms performed in women living in the Goiânia municipality, 8,268 (26.3%) were reported by the diagnostic centers of the SUS network and 23,186 (73.7%) were reported by the private service providers. The monthly mammograms production per the network type is presented on Figure 1. Considering 200 working days, the daily average number of mammograms at the SUS network diagnostic centers was 21 (variation from 18 to 23) per day, while at the private centers the average number of mammograms was 9 (variation from 1 to 21 exams) per day.  Figure 1. Production of mammograms per month and according to the type diagnostic center network, in the municipality of Goiânia, in 2010. Of the total of 31,454 mammograms, 31,198 (99.2%) had clinical indications for screening, and 256 (0.8%) for diagnosis. No significant difference was observed with respect to the proportion of mammograms performed for clinical indications between the SUS network and the service providers network (Table 2). However, of the 13 service providers, six (46.1%) reported to SISMAMA only mammograms with clinical indication for screening.  The distribution of screening mammograms per age group shows that, of the total, 7.4 % of the procedures were performed in the age group < 40 years, 43.3 % were performed in the age group between 40 and 49 years, 31.6% in the age group between 50 and 59 years, 13.2% in women between 60 and 69 years, and 4.5% in women > 70 years. The stratification according type of diagnostic centers network (Figure 2) shows that the age range was not associated with the type of network where the mammography was performed (p = 0.998).  Figure 2. Relative frequency of mammograms reported to SISMAMA according to diagnostic center network type and age group of SUS users in the municipality of Goiânia, in 2010. The frequency of screening mammograms per diagnostic conclusion according to BI-RADS categories show that 3,122 (10%) mammograms were category 0, 17,410 (55.8%) were category 1, 9,494 (30.4%) were category 2, 761 (2.4%) were category 3, 376 (1.2%) were category 4, and 33 (0.1%) were category 5. The diagnostic conclusion was not reported for two mammograms. Table 3 presents the percentage of mammograms per by BI-RADS category stratified by type of network and minimum and maximum percentages observed at the services. It is important to highlight that the SUS' diagnostic centers classified mammograms into all categories, while one of the private centers reported all mammograms (n = 474) as category 1.  In order to evaluate the compliance of the diagnostic centers with respect to the BI-RADS classification of mammograms, Table 4 shows the thresholds within a variation of ± 30% of the mammograms with indication for screening.  On Table 5, it is possible to observe that, among the 15 diagnostic centers performing mammography for SUS in the municipality of Goiânia in 2010, seven were within the thresholds established for compliance in category 0, seven for category 1, six for category 2, three for category 3, four for category 4, and three centers were within the thresholds for category 5. The performance of the diagnostic centers regarding compliance with BI-RADS categories demonstrated that none of the centers complied in all categories: one center was compliant in five categories, two centers were compliant in four categories, three centers were compliant in three categories, two centers in two categories, four centers in one category and three centers did not comply with any category (Table 5). As regards the diagnostic centers performance, Table 5 also demonstrates that the diagnostic centers of the SUS network presented uneven performance. The centers in the private network 4, 5 and 6 presented equality in their performance, with 50% compliance. The centers 10 and 11 also presented equality with 33.33% compliance. Centers 8, 13 and 14 presented equality with 16.67% compliance. And finally, centers 2, 3, and 9 were not compliant in any category. As the mammograms were stratified into inconclusive, normal, requiring radiological follow-up, and altered, the authors observed that 10.01% (3,122) of the mammograms were classified as inconclusive. Normal results were found in 86.24% (29.904) of the mammograms, while those requiring radiological follow-up reached 2.44% (761). Alterations were found in 1.31% (409) of the mammograms. DISCUSSION The Brazilian radiological literature has recently been preoccupied with the relevant role of imaging methods in the improvement of breast diseases diagnosis(22–31). With the consolidation of data at SISMAMA, the evaluation of indicators based on national standards and proposed targets became possible by means of a contextualized observation of mammographic results reported by the SUS' diagnostic centers, allowing greater swiftness in the processing of data necessary for the planning and implementation of public health policies and better allocation of resources in this area(13). In 2010, 45 mammography apparatuses(32) were available for SUS in the state of Goiás. The present study allows inferring that one third of such apparatuses were installed in the Goiânia municipality. As the production of mammograms by SUS is analyzed, Figure 1 suggests that the production curve between the SUS network diagnostic centers and the private service providers presents an oscillation. When there is a decrease in the mammograms production at the SUS network centers, the production at the service providers network increases. Such a fact corroborates other studies which indicate a possible deficiency in the production of mammograms at the SUS services, with such deficiency being compensated and/or suppressed by the service providers network, thus showing a probable dependence of the public sector on private institutions(33,34). The following formula is suggested by INCA to follow-up the productivity of mammography centers: 4 mammograms/hour × 8-hour work shift × 22 days × 12 months × 80% performance. With basis on such formula, the estimated production would be 6,758 mammograms/year, with a mean daily production of 25 mammograms(19). As the present study results are compared with the results from the calculation proposed by INCA, one observes that the mean number of mammograms per day performed at the public mammography centers is close to the expected number (21/day), but the two apparatuses available at the SUS network are not enough to perform biennial mammography in the female population in the age range between 50 and 69 years (111,127) since, according to the INCA parameters(19), 38,894 mammograms/year would be necessary to reach a coverage of 70%(3) of the target population. A consensus is still to be reached with respect to the age range indicated for performing mammography as well as on the mammographic screening periodicity(35,36). Such a fact is also observed in Brazil, as while the Sociedade Brasileira de Mastologia (Brazilian Society of Mastology) recommends that women above the age of 40 undergo mammography every year(37), INCA recommends that women in the age range between 50 and 69(11) years undergo the examination every other year. Since 2009, the Federal Law No. 11,664 dated April 29, 2008 provides that all women in the age of 40 years or more are entitled to undergo mammography at SUS(38). A research undertaken in Goiânia demonstrated a significant increase in the rate of incidence of breast cancer among women in all age groups and that the age group between 50 and 59 years presented a three-fold higher incidence of breast cancer in the period from 1988 to 2003(39,40). In the present study, as the production of screening mammograms was analyzed, the authors observed that 44% of the mammograms were performed on patients in the age range between 40 and 49 years, 31.7% in the age range between 50 and 59 years, and 13.2% in the age range between 60 and 69 years. Such results demonstrate that the prevalence of mammograms is not coincident with the age group with highest breast cancer incidence, and that, like in other studies, the physician-patient relationship seems to be the most significant predictor for the performance of mammography(10,32,41,42). As regards the mammograms with clinical indication for diagnosis, the number reported to SISMAMA by the diagnostic centers corresponded 1.3%, much below the expected 8.9%(19). Such difference may be related to the need for training the professionals who request the mammography, as well as the professionals who report the data from the mammograms to the SISMAMA. The quality of the data reported to the Sistemas de Informação em Saúde (Health Information Systems) has a direct influence on the planning of actions in the healthcare sector(43). As regards the quality of data reported to SISMAMA, one of the private diagnostic centers which reported all mammograms as category 1 corroborates the lack of standardization of mammography reports and the importance of quality control programs. Such lack of standardization may become a factor of confusion in the interpretation of mammograms, as well as interfere in the recommendations for management strategy, with basis on ambiguous mammographic findings(44). Furthermore, the variability in the performance of the diagnostic centers as regards diagnosis conclusion reinforces the findings reported by other studies indicating the need for implementation of audits in screening programs results for monitoring the quality of mammograms interpretation(45–47). One of the requirements included in the Brazilian Ministry of Health Ordinance No. 531/2012 which instituted the PNQM and the Quality Requirements for Mammographic Studies and Reports is the monitoring of the mammogram results reported by imaging diagnosis centers in the whole Brazilian territory(15). With such a monitoring, an equivalent performance regarding diagnostic conclusion is expected from the part of diagnostic centers. As the performance of the diagnostic centers is evaluated, one verifies that their performance is related to a pattern of noncompliance between BI-RADS categories and the thresholds established in the present study. Thus, considering that the SISMAMA is aimed at managing the actions for breast cancer control at different levels, the incorrect input or absence of reported data in the System represents an obstacle to be overcome by public managers as a strategy for planning in health(48). Another important issue is the civil liability of the radiologist in the diagnosis of breast cancer by means of mammography. A study shows that the data transmitted to the to the assisting physician by means of a detailed report(28) with accurate location of possible lesions, as well as correct BIRADS classification, minimize medical errors, thus avoiding civil liability lawsuits(49). For relying on the utilization of secondary data, the limitations faced in the present study are inherent to the inconsistencies of information reported to SISMAMA by each diagnostic center. What is expected from imaging centers that perform mammography for SUS, is homogeneity in the reported data. The consolidated results of the present study allowed the authors to infer that there is a need to promote periodical updating training for the professionals involved in data feeding to SISMAMA, approaching the relevance of a correct filling of fields such as clinical indication, for example. However, besides providing scientific data, the present study allowed for the monitoring of the results from the diagnostic centers, both from the public (SUS) and the private service providers networks, taking into consideration that public (SUS) diagnostic centers are scarce in the municipality of Goiânia and also in the state of Goiás. The monitoring of the results will allow the development of indicators for opportunistic mammographic screening at SUS, and such indicators will contribute with better delineation of actions and health programs on a regionalized basis, as well as will establish decision making strategies targeted at reducing breast cancer morbimortality at a population level. CONCLUSION The results of the present study demonstrate unevenness in the diagnostic centers performance in the classification of mammograms reported to SISMAMA from the opportunistic screening undertaken by SUS, suggesting the necessity of actions for training professionals involved in the data feeding to SISMAMA, as well as in mammography reporting. Acknowledgements To the personnel from the Division of Evaluation and Control of Secretaria Municipal de Saúde de Goiânia, who made the monthly "Data export" files available for the authors; and to Instituto Avon, for the financial support for the revision of the present study. REFERENCES 1. Marchi AA, Gurgel MSC. Adesão ao rastreamento mamográfico oportunístico em serviços de saúde públicos e privados. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2010;32:191–7. 2. Thuler LC. Considerações sobre a prevenção do câncer de mama feminino. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2003;49:227–38. 3. World Health Organization. Cancer control. Knowledge into action: WHO guide for effective programmes. Early detection; module 3. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [acessado em 6 de dezembro de 2010]. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/cancer/modules/Early%20Detection%20Module%203.pdf. 4. Bulliard JL, Ducros C, Jemelin C, et al. Effectiveness of organised versus opportunistic mammography screening. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1199–202. 5. Yip CH, Cazap E, Anderson BO, et al. Breast cancer management in middle-resource countries (MRCs): consensus statement from the Breast Health Global Initiative. Breast. 2011;20 Suppl 2:S12–9. 6. Mackay J, Jemal A, Lee NC, et al. The cancer atlas. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006. 7. Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, et al. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893–907. 8. Lee BL, Liedke PER, Barrios CH, et al. Breast cancer in Brazil: present status and future goals. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e95–e102. 9. Urban LABD, Schaefer MB, Duarte DL, et al. Recomendações do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia e Diagnóstico por Imagem, da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastologia e da Federação Brasileira das Associações de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia para rastreamento do câncer de mama por métodos de imagem. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:334–9. 10. Azevedo AC, Canella EO, Djahjah MCR, et al. Conduta das funcionárias de um hospital na adesão ao programa de prevenção do câncer de mama. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:215–8. 11. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Controle do câncer de mama – Documento de Consenso. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: INCA, 2004. [acessado em 27 de setembro de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www.inca.gov.br/publicacoes/consensointegra.pdf. 12. Viacava F, Almeida C, Caetano R, et al. Uma metodologia de avaliação do desempenho do sistema de saúde brasileiro. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2004;9:711–24. 13. Passman LJ, Farias AMRO, Tomazelli JG, et al. SISMAMA – Implementation of an information system for breast cancer early detection programs in Brazil. Breast. 2011;20 Suppl 2:S35–9. 14. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde: Portaria nº 779, de 31 de dezembro de 2008. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde; 2008. 15. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Gabinete do Ministro. Portaria Nº 531 de 26 de março de 2012. Institui o Programa Nacional de Qualidade em Mamografia – PNQM. Brasília, DF: Diário Oficial da União, Nº 60, Página 91. Seção 1, de 27 de março de 2012. 16. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Sinopse do Censo Demográfico 2010 – Cidades, Goiás. Brasília, DF: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2010. [acessado em 20 de junho de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/cidadesat/topwindow.htm?1. 17. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância do Câncer – CONPREV. Divisão de Gestão da Rede Oncológica – DGRO, 2009. 18. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS. Sistemas e aplicativos. Tabulação. Programa Tab para Windows – TabWin – Versão 3.6b. Brasília. DF; 2008. [acessado em 20 de abril de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=040805&item=3. 19. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Parâmetros técnicos para o rastreamento do câncer de mama. Recomendações para gestores estaduais e municipais. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Instituto Nacional de Câncer; 2009. [acessado em 15 de julho de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www.epsjv.fiocruz.br/beb/textocompleto/009471. 20. American College of Radiology. BI-RADS – Mammography. 4th ed. In: ACR Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, Breast Imaging Atlas. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2003. 21. Godinho ER, Koch HA. Submissão às recomendações do BI-RADS por médicos e pacientes: análise preliminar de 3.000 exames realizados em uma clínica particular. Radiol Bras. 2004;37:21–3. 22. Vianna AD, Gasparetto TD, Torres GC, et al. Cancerização de lóbulos: correlação de achados mamográficos e histológicos. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:275–8. 23. Marques EF, Medeiros MLL, Souza JA, et al. Indicações de ressonância magnética das mamas em um centro de referência em oncologia. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:363–6. 24. Calas MJG, Gutfilen B, Pereira WCA. CAD e mamografia: por que usar esta ferramenta? Radiol Bras. 2012;45:46–52. 25. Miranda CMNR, Santos CJJ, Maranhão CPM, et al. A tomografia computadorizada multislice é ferramenta importante para o estadiamento e seguimento do câncer de mama? Radiol Bras. 2012;45:105–12. 26. Moreira BL, Lima ENP, Bitencourt AGV, et al. Metástase na mama originada de carcinoma ovariano: relato de caso e revisão da literatura. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:123–5. 27. Alvares BR, Freitas CHA, Jales RM, et al. Densidade mamográfica em mulheres menopausadas assintomáticas: correlação com dados clínicos e exames ultrassonográficos. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:149–54. 28. Criado DAB, Braojos FDC, Torres US, et al. Preenchimento estético das mamas com ácido hialurônico: aspectos de imagem e implicações sobre a avaliação radiológica. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:181–3. 29. Barra FR, Barra RR, Barra Sobrinho A. Novos métodos funcionais na avaliação de lesões mamárias. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:340–4. 30. Calas MJG, Alvarenga AV, Gutfilen B, et al. Avaliação de parâmetros morfométricos calculados a partir do contorno de lesões de mama em ultrassonografias na distinção das categorias do sistema BI-RADS. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:289–96. 31. Lykawka R, Biasi P, Guerini CR, et al. Avaliação dos diferentes métodos de medida de força de compressão em três equipamentos mamográficos diferentes. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:172–6. 32. Corrêa RS, Freitas-Junior R, Peixoto JE, et al. Efetividade de programa de controle de qualidade em mamografia para o Sistema Único de Saúde. Rev Saúde Pública. 2012;46:769–76. 33. Corrêa RS, Peixoto JE, Silver LD, et al. Impacto de um programa de avaliação da qualidade da imagem nos serviços de mamografia do Distrito Federal. Radiol Bras. 2008;41:109–14. 34. Corrêa RS, Freitas-Junior R, Peixoto JE, et al. Estimativas da cobertura mamográfica no Estado de Goiás, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2011;27: 1757–67. 35. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:716–26. 36. Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, et al. Screening for breast cancer: systematic evidence review update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:727–37. 37. Sociedade Brasileira de Mastologia. Recomendações da X Reunião Nacional de Consenso. Rastreamento do câncer de mama na mulher brasileira. São Paulo, 2008. [acessado em 3 de julho de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www.sbmastologia.com.br/downloads/reuniao_de_consenso_2008.pdf. 38. Freitas-Junior R, Freitas NMA, Curado MP, et al. Variations in breast cancer incidence per decade of life (Goiânia, GO, Brazil): 16-year analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:681–7. 39. Freitas-Junior R, Freitas NMA, Curado MP, et al. Incidence trend for breast cancer among young women in Goiânia, Brazil. São Paulo Med J. 2010;128:81–4. 40. Martins E, Freitas-Junior R, Curado MP, et al. Evolução temporal dos estádios do câncer de mama ao diagnóstico em um registro de base populacional no Brasil Central. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2009;31:219–23. 41. Brasil. Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa nacional por amostra de domicílios. Um panorama da saúde no Brasil: acesso e utilização dos serviços, condições de saúde e fatores de risco e proteção à saúde – 2008. Rio de Janeiro; 2008. [acessado em 25 de março de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/panorama_saude_brasil_ 2003_2008/PNAD_2008_saude.pdf. 42. World Health Organization. National Cancer Control Programmes: polices and managerial guidelines. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. 43. Feig SA. Screening mammography: a successful public health initiative. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;20:125–33. 44. Vieira AV, Toigo FT. Classificação BI-RADS: categorização de 4.968 mamografias. Radiol Bras. 2002;35:205–8. 45. Perry N, Broeders M, Wolf C, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. 4th ed. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2006. [acessado em 9 de outubro de 2011]. Disponível em: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_projects/2002/cancer/fp_cancer_ 2002_ext_guid_01.pdf. 46. Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography (Review). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. (Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, No. 4). [acessado em 4 de setembro de 2011]. Disponível em: <http://www.cochrane.dk/research/Screening%20for%20breast%20cancer,%20CD001877.pdf>. 47. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Sistemas de informação do controle do câncer de mama (SISMAMA) e do câncer do colo do útero (SISCOLO). Manual gerencial. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Instituto Nacional de Câncer; 2011. 48. Brasil. Lei nº 11.664, de 29 de abril de 2008. Dispõe sobre a efetivação de ações de saúde que assegurem a prevenção, a detecção, o tratamento e o seguimento dos cânceres do colo uterino e de mama, no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS. Brasília, DF: Diário Oficial da União, 30 de abril de 2008. [acessado em 24 de novembro de 2011]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccvil_03/_ato2007-2010/2008?lei/11664.htm. 49. Oliveira FGFT, Fonseca LMB, Koch HA. Responsabilidade civil do radiologista no diagnóstico do câncer de mama através do exame de mamografia. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:183–7. 1. Fellow PhD degree of Health Sciences, Psychologist, Capes scholar, Member of Rede Goiana de Pesquisa em Mastologia – Program of Mastology, Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG), Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 2. PhD, Professor at School of Medicine, Coordinator for the Program of Mastology, Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG), Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 3. PhD, Senior Technologist, Comissão Nacional de Energia Nuclear/Centro Regional de Ciências Nucleares do Centro-Oeste, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 4. PhD, Medical Physicist, Consultant, Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA)/Serviço de Qualidade em Radiações Ionizantes, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 5. Fellow PhD degree in Collective Health, Epidemiologist, Coordination of Strategic Actions, Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 6. PhD, MD, Professor, School of Medicine – Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG), Goiânia, GO, Brazil. * Study developed by the Program of Mastology, Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) – Rede Goiana de Pesquisa em Mastologia, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. Mailing Address: Danielle Cristina Netto Rodrigues Programa de Mastologia, Hospital das Clínicas da UFG 1ª Avenida, s/nº, Setor Universitário Goiânia, GO, Brazil, 74605-050 E-mail: daniellepsinetto@yahoo.com.br Received November 12, 2012. Accepted after revision January 22, 2013. |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554