Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 43 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2010

Vol. 43 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2010

|

ICONOGRAPHIC ESSAY

|

|

Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of perianal fistulas: iconographic essay |

|

|

Autho(rs): Claudio Marcio Amaral de Oliveira Lima1; Flávia Pegado Junqueira2; Mônica Cristina Salazar Rodrigues2; César Augusto Salazar Gutierrez2; Romeu Côrtes Domingues3; Antonio Carlos Coutinho Junior4 |

|

|

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging; Fistula; Perianal; Sphincter; Abscess; Infection. |

|

|

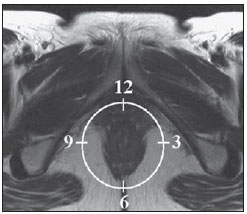

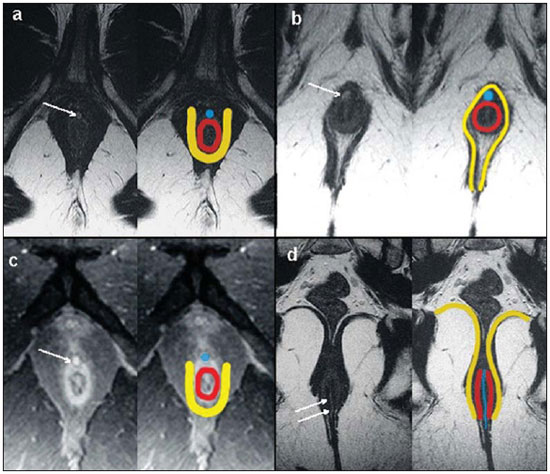

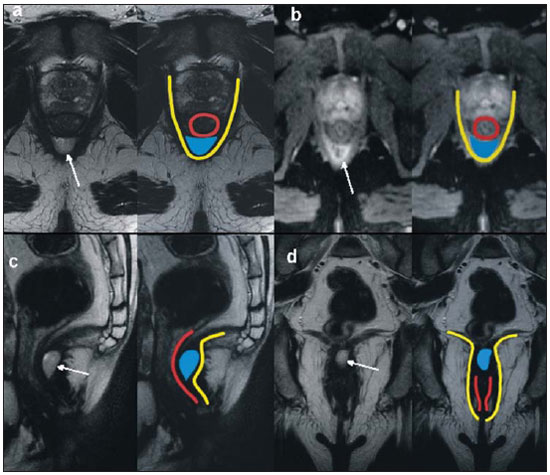

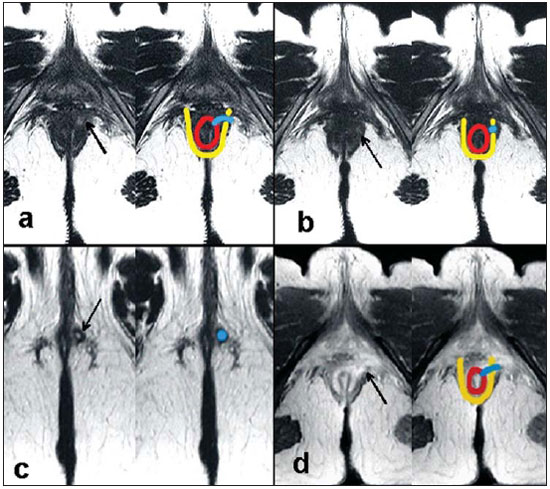

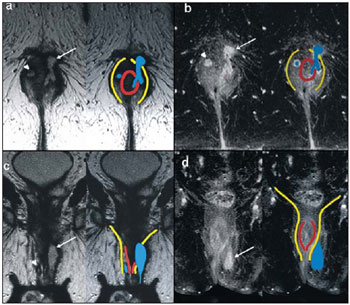

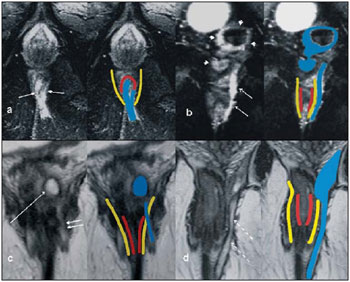

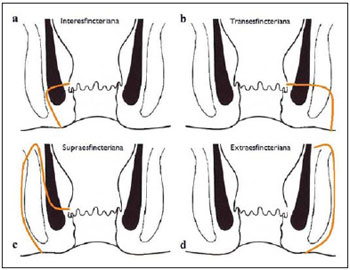

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

Fistula in ano is an uncommon condition of the gastrointestinal tract, with a prevalence of 0.01% in the general population, predominantly affecting young adults, with higher frequency in men than in women at a 2:1 ratio. In about 40% of the cases, this condition is caused by previous anorectal abscesses. It is an important illness because of its high morbidity rate and tendency towards recurrence. Clinically, it manifests with local pain resulting from the inflammatory process, although it may be completely asymptomatic in some patients(1–3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an effective and essential imaging method in the evaluation of fistula in ano, and the multiplanar images acquisition has demonstrated to be extremely useful in the surgical planning, considering its high reliability in the reproduction of perianal anatomy, allowing the characterization and classification of the fistula based on its relation with the pelvic diaphragm and the anal sphincter, evaluating its extent and identifying foci of infection that otherwise would go unnoticed at surgery, contributing for a successful surgical approach and avoiding the disease recurrence(1–4). Considering the frequency and relevance of this disease, the authors describe the main findings observed in the evaluation and classification of fistula in ano by MRI, in the form of an iconographic essay. MRI PROTOCOLS Previous preparation was not required for the study that was performed with an abdominal surface coil, in a Magnetom Avanto 1.5 T equipment (Siemens Medical System; Erlangen, Germany) with, respectively, T2-weighted sequences in the sagittal plane (FOV: 180 mm; thickness: 3.0 mm; GAP: 10%; matrix: 320 × 70; NEX: 3; TA: 2:34 min; TR: 2970; TE: 114), axial plane (FOV: 180 mm; thickness: 3.0 mm; GAP: 0%; matrix: 320 × 70; NEX: 3; TA: 3:43 min; TR: 3660; TE: 114) and coronal plane (FOV: 180 mm; thickness: 3.0 mm; GAP: 10%; matrix: 320 × 70; NEX: 3; TA: 2:33 min; TR: 2500; TE: 114); and T1- weighted sequences in the axial plane (FOV: 240 mm; thickness: 4.0 mm; GAP: 10%; matrix: 256 × 100; NEX: 3; TA: 3:19 min; TR: 516; TE: 6,9); and STIR sequence (FOV: 180 mm; thickness: 3.0 mm; GAP: 10%; matrix: 256 × 126; NEX: 3; TA: 2:57 min; TR: 4790; TE: 24; TI: 150). After intravenous contrast agent injection, T1-weighted sequences were performed with fat suppression in the axial plane (FOV: 230 mm; thickness: 3.0 mm; GAP: 30%; matrix: 256 × 100; NEX: 2; TA: 1:47 min; TR: 511; TE: 7,9) and coronal plane (FOV: 230 mm; thickness 3.0 mm; GAP: 30%; matrix: 256 × 100; NEX: 2; TA: 1:47 min; TR: 511; TE: 7,9). DISCUSSION Fistula in ano is an uncommon but relevant condition, with high morbidity, affecting approximately 10 in 100,000 individuals, with highest frequency in men(4). The anal canal is essentially a cylinder surrounded by two muscles, the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and the external anal sphincter (EAS), respectively composed of smooth and striated musculature. The EAS is the continuation of the levator ani muscle and the IAS is the terminal segment of the intestinal circular muscle(5). The intersphincteric space (ISS) lies between the IAS and the EAS, with a thin fat layer containing flaccid tissue. Laterally to the sphincteric complex is the ischioanal fossa, containing fat and a transverse network of fibroelastic connective tissue(5). The presence of anal glands within the surrounding tissues is variable, and in about two thirds of the population they are located in the ISS. Such glands were first related to fistula in ano by Chiari, who suggested that the glands were the source of infection (cryptoglandular theory)(5). Currently, most studies are in agreement with this hypothesis(5). By definition, a fistula is an abnormal connection between two epithelial surfaces. The anatomic path of a fistula will be determined by the location of the infected anal gland and the adjacent anatomical planes. Surgeons describe the location and direction of the fistulous tract by using the image of a clock face (Figure 1), with a view of the anal region when the patient is in the lithotomy position, corresponding to the view of the anal canal on MRI images in the axial plane, thus facilitating the correlation of imaging findings with those observed during the surgical procedure. Typically, there is an aperture to the anal canal (proximal orifice) at the level of the jagged line, that originally is the gland drainage site; from there the fistula can reach the skin of the perianal region by a variety of tracts and even penetrate and involve with variable degrees the EAS and adjacent tissues(4,5).  Figure 1. Representation of a clock face projected over the anal region on a MRI view in the axial plane. The relation between the fistulas and the perianal musculature is well demonstrated through a combination of images in the different planes, as well as by the different combinations of sequences. The utilization of gadolinium provides excellent contrast between the fistulous tracts and adjacent tissues. MRI is currently the most appropriate method for the diagnosis and classification of such lesions, which is performed according to the pathway between the internal and external apertures of the fistula(4–6). The selection of the coil type depends on individual preference. The utilization of the abdominal surface coil does not require any previous patient preparation and also is very well tolerated. Endoanal coils are poorly tolerated by symptomatic patients and, because of the limited field of view, they may not allow the observation of the full extent of the fistulas. For these reasons and also for the limited availability and acceptance of the endoluminal coil, the abdominal surface coil is used as the standard in cases of fistula in ano(3–5). The role of MRI in the diagnosis of fistula in ano and its complications has been increasing. The imaging findings demonstrate a great agreement with surgical findings, more than at any other imaging method, and the techniques in the several planes demonstrate very well the relation between the fistulous tract with the sphincteric complex and the ischioanal fossa. Another important advantage is its capability of the method to demonstrate clinically occult abscesses(4). Abscesses present high signal intensity on T2- and STIR sequences and iso- or slightly hyperintense signal on T1- weighted sequences, because of the great protein content; eventually such increased content may demonstrate a decrease in signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences. The presence of gas within the abscess is demonstrated by the signal absence on all sequences. The fistulous tracts are seen as tubuliform structures, presenting signal characteristics similar to those of the abscess. After intravenous gadolinium injection, contrast uptake is observed at the thickened abscess and fistulous tract walls, besides a usually hypointense content on T1-weighted sequences. Fistulas in ano classification The fistulas were already known by Hippocrates and have been described along the centuries, receiving special attention in the 19th century, when, in 1835, Frederick Samon founded the Benevolent Dispensary for the Relief of the Poor Afflicted with Fistula and Other Diseases of the Rectum and Lower Intestines, which has become the worldwide famous St. Mark’s Hospital in London, England. Much of what is known about fistulas in ano originates from the work of surgeons in that hospital(4). In 1934, Milligan and Morgan categorized the fistulas location into below, above and within the puborectal muscle, drawing attention to the great likelihood of postoperative incontinence in the case of inappropriate surgical approach of a high fistula. Such classification was modified and refined by other authors, including Parks et al.(7), who have analyzed a consecutive series of 400 patients of the St. Mark’s Hospital, classifying the fistulas into four groups according to the cryptoglandular hypothesis, as follows: intersphincteric, trans-sphincteric, suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric(5,6). The ISS is the pathway with least resistance for infection dissemination, thus raising the suspicion of intersphincteric fistula, observed in 45% of the cases studied by Parks et al., in which the infectious process is limited to the ISS and does not penetrate the ES that represents a natural barrier to the infection dissemination. In a more intense infectious process, the fistulas may cross the ES and reach the ischioanal fossa, resulting in trans-sphincteric type fistula, observed in 30% of the original cases studied by Parks et al. In other circumstances, the fistula may extend to a plane above the ISS, partially surrounding the puborectal muscle and crossing the plateau of the levator ani muscle to reach the perianal skin, resulting in suprasphincteric type fistula, observed in 20% of the cases by Parks et al.(7). They also have found a fourth type of fistula in 5% of the cases, representing an extension of a primary pelvic disease that also crosses the levator ani muscle and goes down through the ischioanal fossa reaching the skin, classified as extrasphincteric type. The classification proposed by Parks et al. was much criticized because of the specific nature of the hospital and also because it did not include the submucosal fistulas, very superficial and not involving the sphincteric structures(5). In 2000, Morris et al.(4), in a study with more than 300 patients at the St. James’s University Hospital (Leeds, England), correlated the Parks et al. classification with MRI findings in the axial and coronal planes, classifying the fistulas into five types as follows: simple linear intersphincteric, intersphincteric with abscess or secondary tract, trans-sphincteric, transsphincteric with abscess or secondary tract in the ischioanal fossa and supra/extrasphincteric. This classification does not deal only with the demonstration of the primary fistulous tract, but also with the secondary branching and associated abscesses. This is an easily acceptable system, considering that it is based on anatomic landmarks in the axial and coronal planes that are very familiar to radiologists, with excellent applicability and reproducibility, as it presents the best correlation with initial surgical evaluation(4). Many fistulas begin as a simple primary tract, but untreated infections may result in branching (secondary tracts), with the ischioanal fossa being the most common site. The horizontal branching of the fistulas is described as “horseshoe shaped” with two tracts in the ISS(5). Type 1: simple linear intersphincteric fistula (Figure 2) – The fistulous tract extends itself from the anal canal to the perineal skin, with a tract confined between the sphincters, with no branching beyond the sphincteric complex. It is by far the most common fistula type . The ischioanal fossae are unaffected(4,5).  Figure 2. Simple linear intersphincteric fistula (type 1). T1-weighted (a) and T1-weighted sequences with fat suppression after gadolinium injection in the axial plane (c) and T2- weighted in the axial plane (b) and in the coronal plane (d) show elongated tubuliform image compatible with fistulous tract located in the anterior intersphincteric space (arrows) with hypersignal intensity on T2-weighted sequence, with parietal contrast-enhancement. Schematic drawing: fistulous tract (blue), internal sphincter (red) and external sphincter (yellow). Type 2: intersphincteric fistula with abscess or secondary tract (Figure 3) – Such fistulas are also confined to a plane between the sphincters, and so do their secondary tracts and/or abscesses. The secondary tracts may be horseshoe-shaped, crossing the midline, or may branch in an ipsilateral intersphincteric plane(4,5).  Figure 3. Intersphincteric fistula with abscess or secondary tract (type 2). T2- weighted sequences in the axial plane (a), sagittal plane (c) and coronal plane (d) and T1-weighted sequence in the axial plane with fat suppression after gadolinium injection (b) show abscess located in the posterior intersphincteric space (arrow). On (c) and (d) one can observe the relationship between the abscess and the external sphincter. Schematic drawing: abscess (blue), internal sphincter (red) and external sphincter (yellow). Type 3: trans-sphincteric fistula (Figure 4) – The fistulous tract crosses the two layers of the sphincteric complex, arching to the skin through the ischioanal fossa. These fistulas also differentiate by the site of entry into the anal canal, which corresponds to the middle third of the anal canal, i.e., at the level of the jagged line, as demonstrated on the images in the coronal plane. As they affect the whole sphincteric complex, surgical treatment may eventually lead to fecal incontinence(4–6).  Figure 4. Trans-sphincteric fistula (type 3). T2-weighted sequence in the axial plane (a,b,c) and T1-weighted sequence in the axial plane after gadolinium injection (d) demonstrate fistulous tract on the left, antero-lateral wall of the anal canal, with contrast uptake. Schematic drawing: Fistulous tract (blue), internal sphincter (red) and external sphincter (yellow). Type 4: trans-sphincteric fistula with formation of abscess or secondary tract within the ischioanal fossa (Figure 5) – Like the type 3 fistulas, the classification into type 4 requires the demonstration that an infectious process occurs through the ES. The abscess may manifest as an expansion along the primary fistulous tract. The tract or associated abscess necessarily involve the ischioanal or ischiorectal fossa and, in some cases, takes over a “dumbbell” shape, crossing the ES(4,5).  Figure 5. Trans-sphincteric fistula with abscess or secondary tract within the ischiorectal fossa (type 4). T2-weighted sequence in the axial plane (a), T1-weighted sequence with fat suppression in the axial plane after gadolinium injection (b), T2-weighted (c) and STIR sequence (d) in the coronal plane demonstrating two fistulous tracts: the primary, trans-sphincteric on the left lateral wall of the anal canal, where one observes an associated abscess (arrow), and the secondary intersphincteric tract at right (arrow head). Schematic drawing: fistulous tract and abscess (blue), internal sphincter (red) and external sphincter (yellow). Type 5: suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric fistula (Figure 6) – If the fistula extends through the ISS, above the levator ani muscle up to the ischiorectal fossa and from there to the skin, it is classified as suprasphincteric fistula; representing the extension of a primary pelvic disease that crosses the levator ani muscle and goes down the ischiorectal fossa reaching the skin, it is classified as extrasphincteric fistula. Such fistulas are difficult to be managed and approached, considering the necessity of additional evaluation for detection of pelvic sepsis. Contrast-enhanced coronal images clearly demonstrate failures in the levator ani muscle, with horseshoeshaped tracts being also a possible finding(4,5).  Figure 6. Extrasphincteric fistula (type 5). STIR sequences in the axial plane (a) and in the coronal plane (b) and T2-weighted sequences in the coronal plane (c,d) demonstrating extrasphincteric fistulous tract (short arrows) extending from a pelvic abscess (arrowheads). On (c) one observes an abscess above the pelvic floor (long arrow) and an extrasphincteric fistulous tract at left (double arrow). On (d) one notices the fistulous tract in the ischioanal fossa at left, which extends from the pelvic abscess at left (dashed arrows). Schematic drawing: fistulous tract and abscess (blue), internal sphincter (red) and external sphincter (yellow). CONCLUSION MRI is an effective and fundamental imaging method for the evaluation of fistulas in ano, and the multiplanar images acquisition has demonstrated to be extremely useful, so the method is considered as the most appropriate for the diagnosis and classification of such lesions (Figure 7). Additional studies have demonstrated that the evaluation by means of MRI is better than the initial surgical exploration in the prediction of outcomes and, as the St. James’ University Hospital is utilized, a significant correlation with better outcomes is observed(4,5).  Figure 7. Schematic drawing of the types of fistula in ano: internal sphincter (black); external sphincter (white); fistulous tracts (orange). REFERENCES 1. Zagrodnik II DF, Schneider M. Fistula-in-ano. Emedicine. [acessado em 15 de fevereiro de 2010]. Disponível em: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/190234-overview 2. Lunnis PJ, Armstrong P, Barker PG, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anal fistulae. Lancet. 1992;340:394–6. 3. Stoker J, Halligan S, Bartram CI. Pelvic floor imaging. Radiology. 2001;218:621–41. 4. Morris J, Spencer JA, Ambrose NS. MR imaging classification of perianal fistulas and its implications for patient management. Radiographics. 2000;20:623–35. 5. Halligan S, Stoker J. Imaging of fistula in ano. Radiology. 2006;239:18–33. 6. Zimmerman DDE. Diagnostic and treatment of transsphincteric perianal fistulas [Doctoral Thesis]. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Erasmus University; 2003. 7. Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg. 1976;63:1–12. 1. MD, Radiologist at Centro de Diagnóstico por Imagem Fátima Digittal, Nova Iguaçu, RJ, Brazil. 2. MDs., Radiologists at Clínica de Diagnóstico Por Imagem (CDPI), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 3. MD, Radiologist, Director for Clínicas Multi-Imagem and Clínica de Diagnóstico Por Imagem (CDPI)/MD.X, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 4. MD, Radiologist at Clínica de Diagnóstico Por Imagem (CDPI)/MD.X, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, and at Centro de Diagnóstico por Imagem Fátima Digittal, Nova Iguaçu, RJ, Brazil. Received March 17, 2010 Accepted after revision May 4, 2010 Study developed at Centro de Diagnóstico por Imagem Fátima Digittal, Nova Iguaçu, RJ, and at Clínica de Diagnóstico Por Imagem (CDPI), Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554