Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 40 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2007

Vol. 40 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2007

|

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

|

|

Computed tomography contribution to the staging of supraglottic squamous cell carcinoma |

|

|

Autho(rs): Antonio Gilson Monte Aragão Jr., Ricardo Pires de Souza, Abrão Rapoport |

|

|

Keywords: Laryngeal neoplasms, Squamous cell carcinoma, Computed tomography, Tumors staging |

|

|

Abstract:

ICourse of Post-Graduation, Department of Head & Neck at Hospital Heliópolis, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

INTRODUCTION Laryngeal cancer is a potentially curable disease. About 30%of these tumors occur in the supraglottis, and 95% of them aresquamous cell carcinomas, with a peak of incidence in the fifthdecade of life and a 5/1 men/women ratio. Radiotherapy andconservative surgery, that can preserve functions such asdeglutition and voice, have made the accurate staging anddefinition of the tumor extent imperative for an appropriatetherapeutic planning. For this purpose, an accurate knowledge ofthe real tumor extent and condition of the laryngealcartilaginous skeleton is indispensable(1–5).Laryngoscopy is of help in the evaluation of the superficialtumor extent, while computed tomography (CT) plays a significantrole in the evaluation of the deep tumor extension, for example,to the preepiglottic and paraglotticspaces)(6–9). The present study is aimed at evaluating the interobserveragreement in the detection of neoplastic involvement in severalsites and extensions of the supraglottic larynx, and theinfluence of CT utilization on the clinical staging as regardshigher levels of the T parameter in the TNM classification ofsupraglottic tumors.

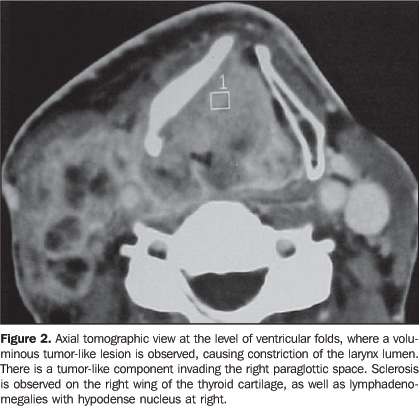

MATERIALS AND METHODS The present study involved inpatients of the Department ofHead & Neck at Hospital Heliópolis, with supraglotticsquamous cell carcinoma, in the period between 1988 and 1998. Thepatients inclusion criteria adopted were the following: a) tumorclinically staged by means of direct/indirect laryngoscopy; b)squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed by biopsy; c) CT studyperformed before any treatment (chemotherapy, radiation therapyor surgery). Thirty-nine dossiers meeting the pre-established criteria wereevaluated. Thirty-three patients (84.6%) were men and six (15.4%)women, corresponding to a men/women ratio of 5.5/1. Patients'ages ranged between 39–74 years among men, and 40–67 years amongwomen, with mean ages of 55 and 53 years, respectively, and 54.9for both sexes. All of these patients were smokers, and 31(79.5%) of them reported moderate or heavy use of alcohol. CT studies were performed on third generation equipment, withacquisition of axial slices with 5 mm thickness and increment,after intravenous, iodinated contrast media injection at a doseof 1.0–2.0 ml/kg, and 60–76% concentration, with the patient insupine position with neck extension, during calm respiration andwithout deglutition. The studies were individually evaluated by two radiologistswith no previous knowledge of findings at physical examinations,laryngoscopic or histopathological studies. The aspects analyzedwere concerned with the T parameter, according to the TNMclassification defined by the International Union Against Cancer(UICC), reviewed in 1997. The evaluation covered tumor extension towards the followingsupraglottic regions: epiglottis, aryepiglottic fold, ventricularfolds and their eventual extensions towards the vocal folds,subglottis, base of the tongue, preepiglottic space, paraglotticspace, thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, and extralaryngealsoft tissues. Deep structures were considered as affected when one or moreof the following criteria were present: blurring of fatty tissuesplanes, local mass effect and direct involvement of the lesion,characterized by the presence of tumor with soft tissues densityin the region to be evaluated. The cartilages invasion wasconsidered in the presence of lesions internal and externally tothe cartilage, or when erosion was detected (these criteria wereutilized for the cartilages evaluated in the present study);sclerosis was the invasion criterion in the evaluation of thecricoid cartilage involvement. The subglottic involvement wasconsidered in the presence of any tissue adjacent to the innersurface of the cricoid cartilage. The staging was based on the T parameters of tumor extentdefined by the UICC (reviewed in 1997). The tomographic stagingwas based on the analysis performed by the most experiencedradiologist specialized in head and neck. The kappa test (k) was utilized in the evaluation of interobserver agreement in the CT studies reading (Chart 1), considering the significance level = 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval(10). Changes in the clinical staging resulting from the CT evaluation were based on the T tumor extent criteria defined by the UICC, observing the regions involved in the upstaging.

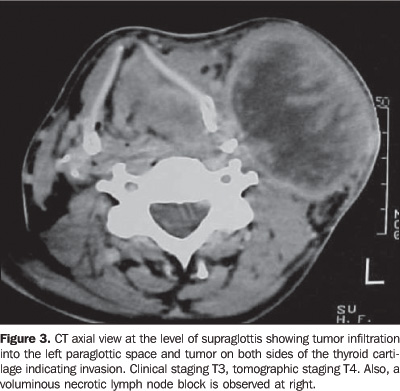

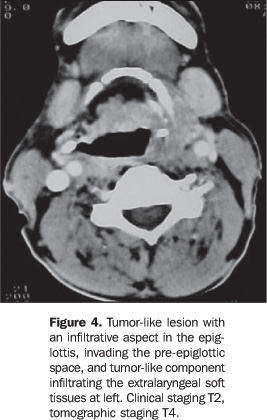

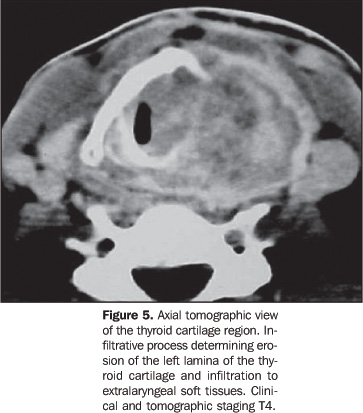

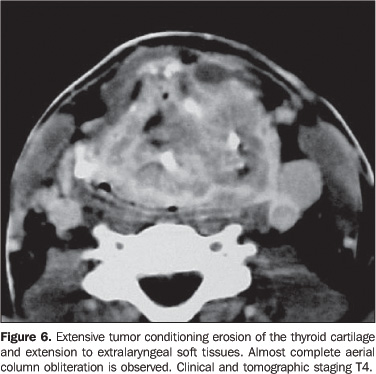

RESULTS 1 – Interobserver agreement Interobserver agreement was considered as good for supraglottic sites — epiglottis (k = 0.655), aryepiglottic folds (k = 0.754), and ventricular folds (k = 0.794). Also, it was considered as good for evaluation of paraglottic (k = 0.693) and preepiglottic (k = 0.744) spaces. The evaluation of vocal folds reached a k = 0.854, with interobserver agreement considered as very good. The agreement was good for evaluation of thyroid cartilage (k = 0.674) and cricoid cartilage (k = 0.687). A regular interobserver agreement (k = 0.480) was found in the evaluation of the base of the tongue; and for the subglottis, the agreement was very good (k = 0.880), and good in the evaluation of the extralaryngeal tumor extension (k = 0.747). 2 – Clinical and tomographic staging At clinical examination, the 39 patients were classified, based on the tumor extent, as follows: two patients (5.1%) T1, 13 (33.3%) T2, 18 (46.2%) T3, and six (15.4%) T4. The reclassification based on CT studies was the following: seven patients (17.9%) T2, 21 (53.8%) T3 and 11 (28.2%) T4. A comparison between clinical and CT staging showed a coincidence in 22 cases (56.4%) — five (12.8%) T2 stage, 12 (30.8%) T3 stage, and five (12.8%) T4 stage (Tables 1 and 2). The two patients with clinical staging T1 were upstaged as T2 and T3 at CT. No patient was staged as T1 by CT (Table 1, Graphic 1).

Of 13 patients (33.3%) with clinical staging T2, only five (38%) were coincidental at CT. The remaining eight patients (61%) were upstaged at CT as follows: seven T3 and one T4. Of 18 patients with clinical staging T3, 12 (67%) were coincidental at CT. The remaining six patients (33%) were not coincidental; five were upstaged as T4. One patient was substaged as T2 at CT (Table 1, Graphic 1). Five of the six (83%) patients clinically staged as T4 had the same result at CT; in only one patient (17%) the CT staging (T3) was different from the clinical staging. This may be explained since there was a clinical suspicion of invasion of the cartilage by the tumor that had not been observed at CT (Table 1). There was a coincidence between clinical and tomographicstaging in 38.5%, 66.7%, and 83.3% of cases respectivelyclassified as T2, T3 and T4. The tomographic staging increased the clinical staging in61.5% of T2-staged cases, and in 27.8% of T3-staged cases. Aspreviously mentioned, two T1-staged cases were upstaged at CT.Two cases were substaged at CT; the first one because the TCfailed to detect vocal fold fixation, decreasing the clinicalstaging from T3 to T2; in the other case, the staging decreasedfrom T3 to T2 as a result of the clinical suspicion of invasionof the cartilage by the tumor that had not been confirmed atCT. Computed tomography has played a decisive role in the upstaging in 15 (38.5%) cases of the whole casuistic according to the factors listed on Table 2.

DISCUSSION According to the literature, CT presents a higher staging accuracy (between 68% and 82.7%) than the clinical examination (between 52% and 74.3%) for supraglottic tumors. This staging accuracy potentialized with the association between CT and clinical evaluations, reaching 91.4% of effectiveness(4,7,11_17).

Also, according to data in the literature, CT determines an increase in clinical staging ranging between 19.4% and 30.7%(3, 12,15,18). In the present study, this upstaging was observed in 38.5% of cases, similarly to the findings of other authors; main reasons were: cartilages invasion, infiltration into the pre-epiglottic and paraglottic spaces, and extralaryngeal tumor extension that had not been detected by laryngoscopy (Table 2). Patients clinically staged as T2 were mostly upstaged at CT. Only two cases clinically staged as T1 met the initial inclusion criteria, and were upstaged. The low number of tumors initially staged as T1 may be explained by: low socio-economic level of the patients, delay in the search for medical assistance, late symptoms in supraglottic tumors, tumors clinically staged as T1 are not routinely submitted to pretherapeutic CT.

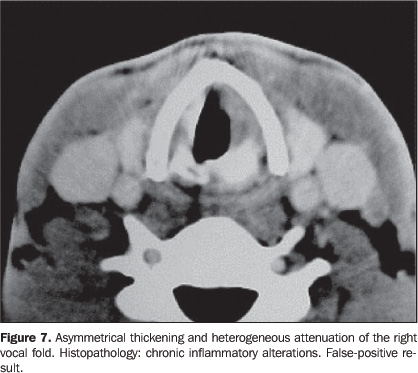

CT may determine a substaging in up to 10.6% of cases(3); in the present study, two cases were substaged at CT in comparison with the clinical examination: one case where the clinical examination had detected fixation of vocal fold (not detected at CT), and another where the CT substaged from T4 to T3, considering the clinical suspicion of cartilage invasion not confirmed by CT. It is important to note that false-positive cases in CTevaluation may occur as a result of inflammatory alterations orperitumoral edema. On the other hand, false-negative cases resultfrom tumors restricted to the mucosal surface or presenting withmicroscopic tumor infiltration(3,19–21). The deep tumor extension into the preepiglottic and paraglottic spaces is neglected in the laryngoscopic evaluation, so CT becomes an essential method in the evaluation of these regions(22,23). The infiltration of these spaces has been implicated in the occurrence of lymph node metastasis(19) and tumor recurrence(24). An association between infiltration of the pre-epiglottic space and invasion of the base of the tongue has been reported(25).

The interobserver agreement was considered as good for all ofthe supraglottic sites, as well as for the pre-epiglottic andparaglottic spaces. An excellent interobserver agreement wasfound in the evaluation of vocal folds and subglottic space. Aprevious study has also demonstrated a good interobserveragreement for supraglottic and subglottic spaces, and very goodfor vocal folds(26). In one case where both observers had considered that the leftvocal fold was infiltrated by the tumor, the histopathologicalanalysis demonstrated that its thickening was a result from achronic inflammatory reaction, characterizing a false-positivecase; this finding being indistinguishable from tumorinfiltration. In another case of disagreement, where clinicalstaging was T3 — because of vocal fold fixation —, theCT substaged as T2, since this method had not detected thisfinding; the histopathological analysis detected the involvementof the vocal fold by the tumor. The relevance of the correlationbetween clinical/endoscopic and tomographic evaluations becomesclear, as the actual tumor extent is established with higheraccuracy. The CT evaluation of laryngeal cartilages is highly specific,however, its sensitivity is low, with a high rate offalse-negative results, and may affect the therapeutic indicationfor partial laryngectomy or radical radiationtherapy(7). Gross cartilage destruction may beeasily identified, while mild macroscopic or microscopicinvasions are unlikely to be detected byCT(4,27–29). The irregular calcificationpattern is the factor that represents one of the majordifficulties in the evaluation of cartilages, especially thyroidcartilage(8,28–30). Good interobserveragreement was found for evaluation of tumor invasion of thethyroid cartilage and cricoid cartilage. Hermans etal.(30) have found an interobserver agreementconsidered as just regular. This may be explained by the factthat infiltration criteria were adopted for each of thecartilages. Sclerosis was considered as a sign of infiltrationjust for the cricoid cartilage, since infiltration into thethyroid cartilage frequently is just an indication ofinflammatory reaction(5). The CT evaluation of the base of the tongue is not effectiveprincipally because of secretions deposition that may simulatetumor involvement, as well as the presence of redundant lymphatictissue(3,17). CT failed to identify one thirdof cases of infiltration into the base of the tongue.Interobserver agreement was considered as just regular in theevaluation of tumor infiltration into the base of the tongue. Thehistopathological analysis demonstrated two patients with thisfinding, one of them identified by both observers, and the other,by only one observer. These two cases presented invasion of thepreepiglottic space confirmed by anatomopathologicalanalysis. Subglottic invasion may occur both by superficial mucosaldissemination and lateral infiltration of the elasticcone(3). On the other hand, tumor extension toother extralaryngeal soft tissues may occur through the larynx orthyrohyoid or cricoid membranes(17).Laryngoscopy is useful in the evaluation of subglottis, but itsaccuracy may be impaired in case of exophytic tumors, andextralaryngeal extension may not be detected; this is one of themain reasons for clinical substaging(7). CT mayrepresent a useful tool in this evaluation, presenting a verygood interobserver agreement for subglottis, and good forextralaryngeal extension. The adequate reproducibility of the method is demonstrated bythe good interobserver agreement, in spite of the lack ofopportunity to compare data with histopathological resultsregarding each of the sites evaluated for different reasons likeincomplete pathology reports or patients who had not beensubmitted to surgery. It should ever be held in mind thatfalse-positive results do occur (due to reactionaledema/thickening), and that they are indistinguishable from tumorinfiltration findings, and so do false-negative results (due tomicroscopic invasion, or limited to the mucosal surface —undetectable by the current tomographs), possibly leading tosubstaging. However, the good CT reproducibility becomes moresignificant in face of the tendency towards more conservative,and frequently non-surgical treatments for laryngeal tumors. As aresult CT becomes an important tool in the pretherapeuticevaluation of these patients.

CONCLUSIONS In the present study, computed tomography presented a verygood interobserver agreement in the evaluation of tumorinvolvement in the vocal folds and tumor extension into thesubglottis. Interobserver agreement was considered as good foranalysis of epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, ventricular folds,preepiglottic space, paraglottic space, thyroid and cricoidcartilages, and for evaluation of extralaryngeal tumor extension.For evaluation of tumor involvement in the base of the tongue,the interobserver agreement was considered as regular. CT upstaged 38.5% of patients with supraglottic cancer. Thegreatest difference between clinical and tomographic stagings wasfound in the group of patients with clinically staged T2 tumors,and CT upstaged 61.5% of these patients.

REFERENCES 1. Sagel SS, AufderHeide JF, Aronberg DJ, Stanley RJ, Archer CR. High resolution computed tomography in the staging of carcinoma of the larynx. Laryngoscope 1981;91:292–300. [ ] 2. Sexton CC, Anderson CG. Computed tomography in carcinoma of the larynx. Australas Radiol 1984;28:330–334. [ ] 3. Charlin B, Brazeau-Lamontagne L, Guerrier B, Leduc C. Assessment of laryngeal cancer: CT scan versus endoscopy. J Otolaryngol 1989;18: 283–288. [ ] 4. Sulfaro S, Barzan L, Querin F, et al. T staging of the laryngohypopharyngeal carcinoma. A 7-year multidisciplinary experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989;115:613–620. [ ] 5. Becker M, Zbären P, Delavelle J, et al. Neoplastic invasion of the laryngeal cartilage: reassessment of criteria for diagnosis at CT. Radiology 1997;203:521–532. [ ] 6. Zbären P, Becker M, Lang H. Pretherapeutic staging of laryngeal carcinoma. Clinical findings, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging compared with histopathology. Cancer 1996;77:1263–1273. [ ] 7. Zbären P, Becker M, Lang H. Staging of laryngeal cancer: endoscopy, computed tomography and magnetic resonance versus histopathology. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1997;254 Suppl 1:S117–S122. [ ] 8. Kazkayasi M, Önder T, Özkaptan Y, Can C, Pabusçu Y. Comparison of preoperative computed tomographic findings with postoperative histopathological findings in laryngeal cancers. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1995;252:325–331. [ ] 9. Mukherji SK, Pillsbury HR, Castillo M. Imaging squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract: what clinicians need to know. Radiology 1997;205:629–646. [ ] 10. Pereira MG. Epidemiologia: teórica e prática. 1ª ed. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Guanabara Koogan, 1995. [ ] 11. Katsantonis GP, Archer CR, Rosenblum BN, Yeager VL, Friedman WH. The degree to which accuracy of preoperative staging of laryngeal carcinoma has been enhanced by computed tomography. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986;95:52–62. [ ] 12. Deschepper C, Casselman J, Van de Voorde W, Lemahieu S, Van Damme B, Baert AL. The contribution of CT to the T-staging of laryngeal carcinoma. J Belge Radiol 1989;72:191–197. [ ] 13. Kolbenstvedt A, Charania B, Natvig K, Tausjo J. Computed tomography in T1 carcinoma of the larynx. Acta Radiol 1989;30:467–469. [ ] 14. Werber JL, Lucente FE. Computed tomography in patients with laryngeal carcinoma: a clinical perspective. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1989;98(1 Pt 1):55–58. [ ] 15. Dullerud R, Johansen JG, Dahl T, Faye-Lund H. Influence of CT on tumor classification of laryngeal carcinomas. Acta Radiol 1992;33:314–318. [ ] 16. Thabet HM, Sessions DG, Gado MH, Gnepp DA, Harvey JE, Talaat M. Comparison of clinical evaluation and computed tomographic diagnostic accuracy for tumors of the larynx and hypopharynx. Laryngoscope 1996;106(5 Pt 1):589–594. [ ] 17. Williams DW 3rd. Imaging of laryngeal cancer. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1997;30:35–58. [ ] 18. Barbera L, Groome PA, Mackillop WJ, et al. The role of computed tomography in the T classification of laryngeal carcinoma. Cancer 2001;91:394–407. [ ] 19. Larsson S, Mancuso A, Hoover L, Hanafee W. Differentiation of pyriform sinus cancer from supraglottic laryngeal cancer by computed tomography. Radiology 1981;141:427–432. [ ] 20. Reid MH. Laryngeal carcinoma: high-resolution computed tomography and thick anatomic sections. Radiology 1984;151:689–696. [ ] 21. Silverman PM, Bossen EH, Fisher SR, Cole TB, Korobkin M, Halvorsen RA. Carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx: computed tomographic-histopathologic correlations. Radiology 1984; 151:697–702. [ ] 22. Weinstein GS, Laccourreye O, Brasnu D, Yousem DM. The role of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in planning for conservation laryngeal surgery. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 1996;6:497–504. [ ] 23. Dursun G, Keser R, Aktürk T, Akiner MN, Demireller A, Sak SD. The significance of pre-epiglottic space invasion in supraglottic laryngeal carcinomas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1997;254 Suppl. 1:S110–112. [ ] 24. Hermans R, Van den Bogaert W, Rijnders A, Baert AL. Value of computed tomography as outcome predictor of supraglottic squamous cell carcinoma treated by definitive radation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;44:755–765. [ ] 25. Gregor RT. The preepiglottic space revisited: is it significant? Am J Otolaryngol 1990;11:161–164. [ ] 26. Paiva RGS, Souza RS, Rapoport A, Soares AH. Avaliação por tomografia computadorizada do envolvimento loco-regional do carcinoma espinocelular de corda vocal. Radiol Bras 2001;34:193–200. [ ] 27. Mafee MF, Schild JA, Michael AS, Choi KH, Capek V. Cartilage involvement in laryngeal carcinoma: correlation of CT and pathologic macrosection studies. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1984;8: 969–973. [ ] 28. Castelijns JA, Gerritsen GJ, Kaiser MC, et al. Invasion of laryngeal cartilage by cancer: comparison of CT and MR imaging. Radiology 1988;167: 199–206. [ ] 29. Castelijns JA, Golding RP, Van Schalk C, Valk J, Snow GB. MR findings of cartilage invasion by laryngeal cancer: value in predicting outcome of radiation therapy. Radiology 1990;174(3 Pt 1): 669–673. [ ] 30. Hermans R, Van der Goten A, Baert AL. Image interpretation in CT of laryngeal carcinoma: a study on intra- and interobserver reproducibility. Eur Radiol 1997;7:1086–1090. [ ]

Received January 12, 2006. Accepted after revision November 23, 2006.

* Study developed at Hospital Heliópolis, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554