Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 40 nº 1 - Jan. /Feb. of 2007

Vol. 40 nº 1 - Jan. /Feb. of 2007

|

WHICH IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

|

|

Qual o seu diagnóstico? |

|

|

Autho(rs): Marcelo Souto Nacif, Amarino Carvalho de Oliveira Júnior, Denise Madeira Moreira, Mônica Regina Nagano, José Hugo Mendes Luz, Paulo Roberto Dutra da Silva, Carlos Eduardo Rochitte |

|

|

IProfessor at Faculdade de Medicina de Teresópolis, Sub-coordinator for Post-Graduation at Instituto de Pós-Graduação Médica Carlos Chagas, Master in Radiology (Magnetic Resonance Imaging Angiography) by Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

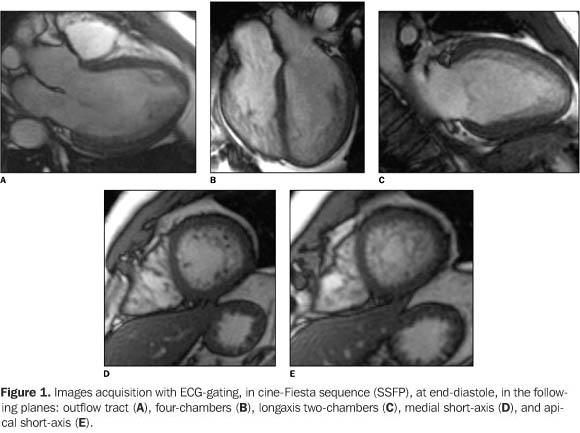

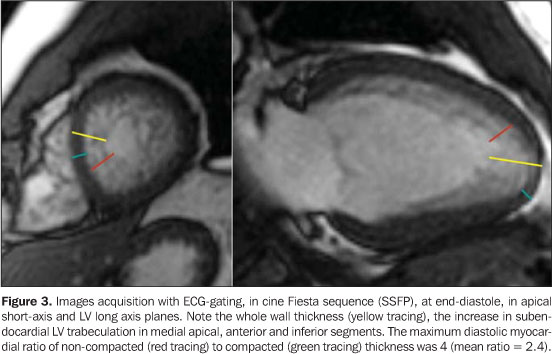

A male, 38-year old patient, weighting 82 kg, 1.78 m in height, with non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, has been referred to the Service of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging at Hospital Procardíaco to be submitted to magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the heart. Images description Figure 1. Images acquisition with ECG-gating, in cine Fiesta sequence (SSFP), at end-diastole, in the following planes: outflow tract (A), four-chambers (B), long-axis – two-chambers (C), medial short-axis (D), and apical short-axis (E). Observe normal sized atriums, right ventricle with preserved diameters; the right ventricular global and segmental function was preserved. The left ventricle (LV) presents with slightly increased diastolic diameter, with preserved global and segmental function. Note the increase in subendocardial LV trabeculation in medial apical, anterior and inferior segments. The maximum diastolic myocardial ratio of non-compacted (N/C) to compacted (C) thickness was 4 (mean ratio = 2.4).

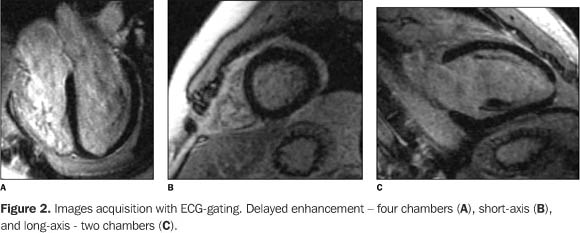

Figure 2. Images acquisition with ECG-gating. Delayed enhancement – four-chambers (A), short-axis (B), and long-axis – two-chambers (C). Observe the absence of delayed myocardial enhancement, compatible with absence of myocardial necrosis/fibrosis.

Diagnosis: Isolated non-compacted myocardium.

COMMENTS Non-compacted myocardium is a rare disease, usually diagnosedin the pediatric population, and associated with other structuralcongenital malformations of the heart, predominating in patientswith congenital left or right ventricular outflow tractobstruction(1,2). Isolate non-compactedmyocardium, defined by the absence of other associate structuralalteration of the heart, is an even more rare presentation, andhas been poorly reported in theliterature(2). Also called LV hypertrabeculation, spongy myocardium orisolated LV abnormal trabeculation, this disease was firstlydescribed in 1932, after necropsy. So far, a few cases have beenreported in the Brazilian literature. Its estimated prevalencewas 0.05% to 0.24%, but, with the current development ofdiagnostic imaging methods, especially in the field of MRI, thisprevalence tends to increase(1–4). The etiology of non-compacted myocardium is still to bedefined, but heterogeneous genetic factors seem to be closelyconnected with this disease. During the initial phase ofembryonic development, the heart is a trabecular net with aspongy myocardium. The intertrabecular spaces communicate withthe cardiac chambers. As the heart develops, the myocardiumcondenses and the intertrabecular recesses are reduced tocapillaries. Non-compacted myocardium is defined as an anomaly ofendomyocardial morphogenesis, and it is believed to be an arrestin the compaction of the myocardial fibers, which meet forming aninterwoven loose net during intrauterine life. Persistence ofnon-compacted myocardium is a rare entity, usually diagnosed inthe pediatric population and associated with other structuralcongenital malformations of the heart. It predominates inpatients with congenital obstruction of the right or leftventricle outflow tract. The isolate non-compacted myocardium canbe detected from the infancy to adulthood. Both sexes areaffected and familial recurrence may occur. Familialstratification by cardiac MRI should be considered in relativesof patients with diagnosis of isolated non-compacted myocardium.The present case is in agreement with the literature, where caseswith a good myocardial function and absence of constantarrhythmia may present a good prognosis. There is evidence ofassociation with heart failure, severe arrhythmias and embolicevents(3–5). In the majority of reports in the literature, the ventricular non-compaction is associated with other congenital cardiopathies, with predominance of pulmonary atresia and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction combined with an intact interventricular septum. Non-compacted myocardium also has been identified in association with abnormalities in the origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery trunk. In the case of isolated non-compacted myocardium (Figure 3), its cause remains unknown, and no factor justifying the arrest of ventricular myocardial compaction has been identified. The diagnosis of isolated non-compacted myocardium would be based on a MRI study showing numerous and excessively prominent trabeculations and deep intertrabecular recesses in the absence of coexistent cardiac abnormalities. Contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography and MRI studies are complementary and useful for diagnostic confirmation enabling the differentiation between compacted and non-compacted tissues(1,5–7).

Clinical findings may vary from asymptomatic patients topatients with progressive left ventricular dysfunction witharrhythmias and systemic and pulmonary embolic phenomena. Indilated cardiomyopathy, some degree of inferoapical trabeculationassociated with the intertrabecular spaces may be visualized;therefore, a distinction between these two disorders, at leastfrom the morphological point of view, is not always clear. Inspite of the fact that demonstration on perfusion MRI of deepperfused intertrabecular recesses is one of the markers for thediagnosis of isolated non-compacted myocardium, transitionalvariations between the isolated non-compacted myocardium anddilated cardiomyopathy may exist(6–10). Inaddition, more discreet cases of isolated noncompacted myocardiumwithout diagnostic confirmation may exist, in the absence ofexcessive trabeculation in the inferoapical region, hypertrophy,and marked intertrabecular recesses. The high incidence ofthromboembolic phenomena in the isolated non-compacted myocardiumcould result in formation of local thrombi in the deepintertrabecular recesses in addition to ventriculardysfunction(4,9–11). MRI represents an extremely important method not only for diagnosis, but also for following-up the clinical evolution of these patients.

REFERENCES 1. Bellet S, Gouley BA. Congenital heart disease with multiple cardiac anomalies: report of a case showing aortic atresia, fibrous scar in myocardium, and embryonal sinusoidal remains. Am J Med Sci 1932;183:458–465. 2. Chin TK, Perloff JK, Williams RG, Jue K, Mohrmann R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium: a study of eight cases. Circulation 1990;82:507–513. 3. Conces DJ Jr, Ryan T, Tarver RD. Noncompaction of ventricular myocardium: CT appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;156:717–718. 4. Dusek J, Estadal B, Duskova M. Postnatal persistence of spongy myocardium with embryonic blood supply. Arch Pathol 1975;99:312–317. 5. Lauer RM, Fink HP, Petry EL, Dunn MI, Diehl AM. Angiographic demonstration of intramyocardial sinusoids in pulmonary-valve atresia with intact ventricular septum and hypoplastic right ventricle. N Engl J Med 1964;271:68–72. 6. Oechslin EN, Jost CHA, Rojas JR, Kaufmann PA, Jenni R. Long-term follow-up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:493–500. 7. Ritter M, Oechslin EN, Sütsch G, Attenhoffer C, Schneider J, Jenni R. Isolated noncompaction of the myocardium in adults. Mayo Clin Proc 1997; 72:26–31. 8. Robida A, Hajar HA. Ventricular conduction defect in isolated noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium. Pediatr Cardiol 1996;17:189–191. 9. Jenni R, Wyss CA, Oechslin EN, Kaufmann PA. Isolated ventricular noncompaction is associated with coronary microcirculatory dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:450–454. 10. Stöllberger C, Finsterer J. Left ventricular noncompaction, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and neuromuscular disorders. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:1233–1234. 11. Wong JA, Bofinger MK. Noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium in Melnick-Needles syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1997;71:72–75.

Study developed at Hospital Procardíaco, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554