Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 52 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2019

Vol. 52 nº 5 - Sep. / Oct. of 2019

|

PICTORIAL ESSAY

|

|

The many faces of primary and secondary hepatic lymphoma: imaging manifestations and diagnostic approach |

|

|

Autho(rs): Aldo Maurici Araújo Alves1; Ulysses Santos Torres2; Fernanda Garozzo Velloni3; Bruno Juca Ribeiro4; Dario Ariel Tiferes5; Giuseppe D’Ippolito6 |

|

|

Keywords: Lymphoma; Liver; Magnetic resonance imaging; Tomography, X-ray computed. |

|

|

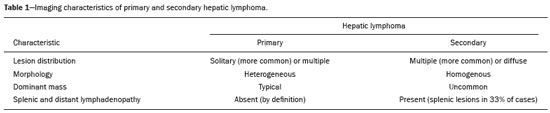

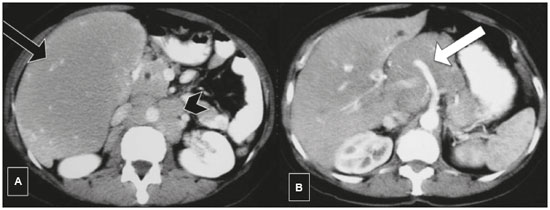

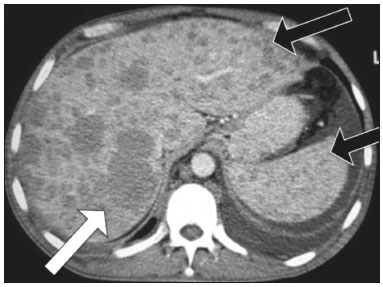

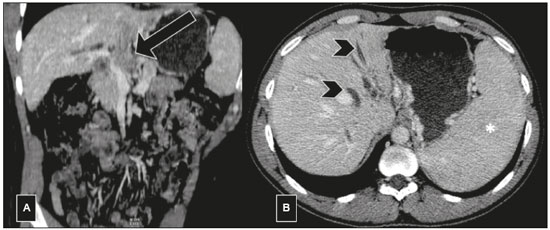

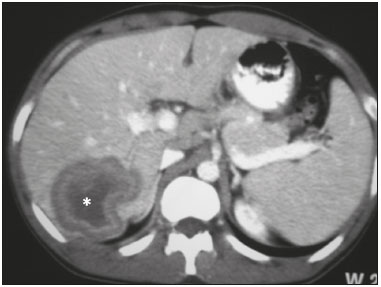

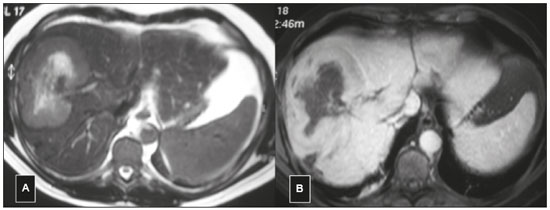

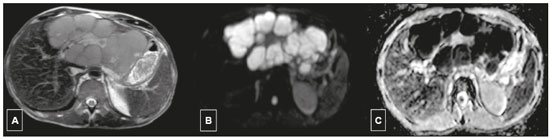

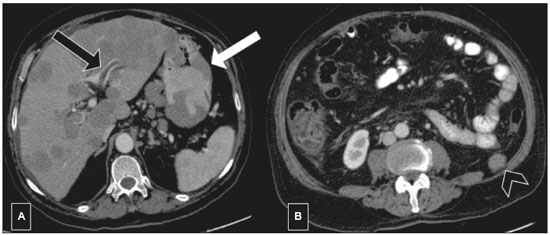

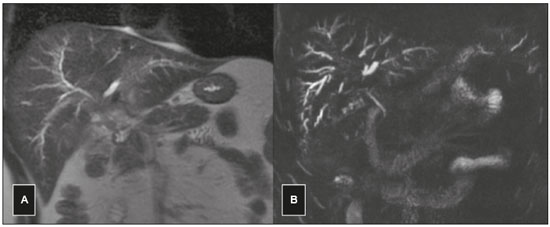

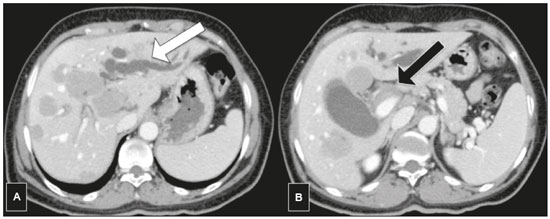

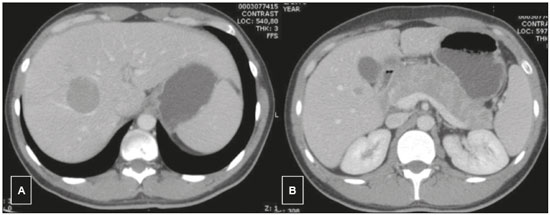

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

Hepatic lymphoma can be divided into a primary form and a secondary (metastatic) form, the two forms having different prognoses. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma predominates in both forms(1). To be classified as primary hepatic lymphoma, the disease should be limited to the liver and hilar lymph nodes, with no distant involvement. According to some authors, the diagnosis of primary hepatic lymphoma also requires the absence of distant disease (distant lymphadenopathy, splenic infiltration or bone marrow disease) within six months of diagnosis(2). The most common extranodal site of involvement by non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the gastrointestinal tract, secondary hepatic lymphoma being observed in nearly half of all patients with such involvement. However, primary hepatic lymphoma is quite rare, accounting for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas(3). Although the pathophysiology of primary hepatic lymphoma is poorly understood, it has been associated with prolonged immunosuppression (including that caused by infection with HIV) and Epstein-Barr virus, as well as with hepatitis B and C. The most common subtype of primary hepatic lymphoma is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma(4). The clinical manifestations of primary and secondary hepatic lymphoma include hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, and systemic (B) symptoms (fever, weight loss, and night sweats)(1). Imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of cases of hepatic lymphoma, being used not only to evaluate the evolution of the disease but also to guide relevant procedures. The management and prognosis of lymphoma are remarkably different from those of other neoplasms. Hence, familiarity with the imaging features of hepatic lymphoma is important for its early diagnosis and appropriate management. IMAGING FINDINGS Hepatic lymphoma has a wide range of imaging presentations, typically being evaluated on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It can appear as a solitary (homogeneous or heterogeneous) mass or as multiple lesions, with or without a dominant lesion, or even in a miliary pattern characterized by multiple small discrete nodules. Other patterns include diffuse infiltration (with or without hepatomegaly) and a mass in the porta hepatis. Rarer forms with no defined imaging pattern can also be seen. The most common manifestation of primary hepatic lymphoma is a heterogeneous solitary mass (Figure 1), whereas multiple lesions are seen in less than 33% of cases(5). The diffuse form of primary hepatic lymphoma is uncommon and is associated with a poor prognosis. More than one pattern may be present in the same patient(5).  Figure 1. Axial portal venous CT image showing a solitary heterogeneous mass in the left lobe of the liver, with a rim-enhancement (target-like) pattern. The spleen and periportal nodes were not involved (not shown). The final diagnosis was primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as confirmed by biopsy. Secondary hepatic lymphoma typically presents as diffuse infiltration (Figure 2) or multifocal homogeneous lesions along with extrahepatic disease (splenic lesions, lymphadenopathy, bone marrow infiltration, etc.). A miliary pattern is more common in secondary hepatic lymphoma (Figure 3).  Figure 2. Axial contrast-enhanced CT images (A,B) showing diffuse infiltration of the liver parenchyma and hepatomegaly. There is encasement without occlusion of the hepatic vessels (black arrow) or celiac trunk (white arrow). Diffuse enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes (arrowhead) are also noted. CT-guided biopsy of the liver resulted in a diagnosis of secondary hepatic non-Hodgkin lymphoma.  Figure 3. Secondary hepatic lymphoma. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image showing multiple homogeneous hypoattenuating hepatic lesions (white arrow) and multiple small hepatic and splenic nodules in a miliary pattern (black arrows). There was also prominent retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (not shown). Although the imaging findings of primary hepatic lymphoma and secondary hepatic lymphoma may overlap, some features can facilitate the diagnostic discrimination. Dominant liver lesions, which tend to be heterogeneous (Figure 1), are characteristic of primary hepatic lymphoma and are not expected to be found in secondary hepatic lymphoma. In addition, even large secondary hepatic lymphoma lesions tend to be homogeneous before chemotherapy. Table 1 lists the imaging characteristics of the primary and secondary forms. Another form of presentation of primary or secondary hepatic lymphoma is a periportal mass, which generally presents as an ill-defined, infiltrating, homogeneous and poorly enhancing hilar tissue (Figure 4).  Figure 4. A 32-year-old man with jaundice. On portal phase CT images, a hypovascular lesion is noted in the form of periportal tissue involving the portal vein (black arrow) and the bile duct, with dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts (arrowheads). Splenomegaly is also seen (asterisk). Analysis of a biopsy sample indicated that the lesion was non-Hodgkin lymphoma (secondary hepatic lymphoma). CT and MRI features On CT, hepatic lymphoma shows soft tissue attenuation. Necrosis or hemorrhage can also be seen. Calcification is quite rare before treatment. The majority of hepatic lesions show minimal enhancement after the intravenous administration of a contrast agent. Rim enhancement (a target-like lesion) has also been described(6) and is more common in primary hepatic lymphoma (Figures 1 and 5).  Figure 5. Primary hepatic non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Axial venous phase CT image showing a solitary heterogeneous mass, with a target-like appearance, in the right lobe of the liver. Note the large nonenhancing central area (asterisk), consistent with necrosis. On MRI, hepatic lymphoma lesions tend to show hypointense or isointense signals on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and hyperintense signals on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI). Although such lesions typically show a homogenous signal, necrosis or hemorrhage can cause some heterogeneity(1). A target-like appearance on T2WI, as depicted in Figure 6, has also been described(1).  Figure 6. Primary hepatic lymphoma with a target-like appearance on MRI. Axial T2WI (A) showing a solitary mass, with a signal that is hyperintense in its center and hypointense at its periphery, in the right lobe of the liver. Axial gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRI scan (B) showing a rim-enhancement pattern. The pattern of enhancement in hepatic lymphoma is similar on CT and MRI. Central retention of hepatobiliary contrast agent in the delayed (hepatobiliary) phase has been reported(1). On diffusion-weighted imaging, hepatic lymphoma lesions usually demonstrate markedly restricted diffusion, which is explained by their highly cellular histology (Figure 7). On 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (FDG-PET/CT), primary and secondary lesions both typically show avid hypermetabolism, FDG-PET/CT also being considered the imaging modality of choice for staging and for assessing treatment responses(6). However, whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging also allows pre- and post-treatment staging, providing results comparable to those of FDG-PET/CT(7).  Figure 7. A 49-year-old man with weight loss and night sweats. MRI images show hyperintensity on T2WI (A), as well as markedly restricted diffusion on diffusionweighted imaging with a b value of 1000 s/mm2 (B) and on an apparent diffusion coefficient map (C). The mean apparent diffusion coefficient value was 450 × 10−6 mm2/s. The final diagnosis was primary hepatic Burkitt’s lymphoma, as confirmed by biopsy and immunochemistry. Imaging tips In addition to clinical and laboratory data favoring the diagnosis of hepatic lymphoma (e.g., a young age, B symptoms, and abnormal bone marrow biopsy), imaging features can contribute to the diagnostic discrimination. Vascular or biliary encasement without thrombosis or ductal dilatation may occur in some cases of hepatic lymphoma (Figure 2), owing to the absence of fibrous stroma and desmoplastic tissue(6); that is, these lymphomas may be sufficiently malleable to mold and grow throughout the periportal space without causing substantial compression of the biliary or vascular tree. That feature may be observed in intrahepatic (diffuse or mass-forming) and periportal lesions(6). The coexistence of splenic lesions and extensive (supra- or infra-diaphragmatic) nodal disease favors a diagnosis of secondary hepatic lymphoma. An enlarged posterior iliac crest lymph node is a classic sign of lymphoma (Figure 8), although it is not pathognomonic, because lymph nodes in this region may also be involved secondary to the dissemination of pelvic malignancies.  Figure 8. A 70-year-old man with dyspepsia and weight loss. Axial contrast-enhanced CT images showing multiple homogenous hepatic nodules without a dominant mass. Note thrombosis of the left portal vein (black arrow in A), multiple homogeneous lesions in the gastric wall (white arrow in A), and the enlarged lymph node slightly above the left posterior iliac crest (arrowhead in B). The final diagnosis was non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as confirmed by endoscopic biopsy. Rarer forms of hepatic lymphoma Primary lymphoma arising from the bile duct (Figure 9) is extremely rare, with imaging features overlapping those of cholangiocarcinoma(8). Other rare forms of hepatic lymphoma include intravascular hepatic lymphoma(9) and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma(10), both of which have been scarcely reported in the literature and have no specifically defined imaging pattern.  Figure 9. A 28-year-old man with jaundice. MRI showing an ill-defined, infiltrative mass extending from the porta hepatis to the parenchyma following the portal triads. Coronal T2WI (A) showing an area with a slightly hyperintense signal. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (B) showing dilatation of the segmental bile ducts. These imaging characteristics are indistinguishable from those of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The final diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, as confirmed by biopsy. Atypical findings, mimics, and the differential diagnosis Although not typical, portal vein thrombosis (Figure 8) and bile duct obstruction may occur in hilar and periportal hepatic lymphoma (Figures 4 and 9) as well as in mass-forming intrahepatic lesions (Figure 10). Hepatic lymphoma has a wide range of differential diagnoses and can mimic many conditions, such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, inflammatory pseudotumor, and primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor. In addition, because infection with hepatitis C or B virus is also a risk factor for primary hepatic lymphoma, a solitary infiltrative lymphoma in the setting of cirrhosis may be difficult to differentiate from the diffuse form of hepatocellular carcinoma. Albeit uncommon, primary hepatic lymphoma can have an appearance similar to that of hepatocellular carcinoma on contrast-enhanced images. The differential diagnoses of the multifocal form of hepatic lymphoma include granulomatous diseases, fungal infections, and metastasis. Especially in immunosuppressed patients, including those with HIV infection, which is a risk factor for lymphoma (Figure 11), it can be difficult to make the distinction among those entities on the basis of imaging findings alone(1). The diffuse form of hepatic lymphoma may also be confused with acute hepatitis(1). On imaging, the rare primary biliary subtype of lymphoma and hepatic lymphoma manifesting as a mass in the porta hepatis, as depicted in Figures 4 and 9, respectively, may be indistinguishable from cholangiocarcinoma(8).  Figure 10. Secondary hepatic lymphoma in a 58-year-old woman with B symptoms, presenting with the intrahepatic mass-forming and periportal forms. Severe dilatation of the bile duct in the left lobe of the liver (white arrow in A) caused by a periportal lesion (black arrow in B). The final diagnosis was Burkitt’s lymphoma, as confirmed by biopsy of the left inguinal lymph node (not shown).  Figure 11. A 33-year-old man with HIV infection and abdominal pain. Axial contrast-enhanced CT showing hypodense hepatic lesions (A,B) and multiple hypodense nodules throughout the pancreas. The final diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, as confirmed by biopsy. CONCLUSION CT and MRI play important roles in the management of hepatic lesions, including lymphoma. Although there are no specific imaging features for hepatic lymphoma and biopsy is nearly always necessary, familiarity with the most common imaging features can promote early suspicion and appropriate management, which can improve the prognosis. Acknowledgment The authors thank Dr. Henrique Simão Trad (Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil) for kindly having provided the case of figure 9. REFERENCES 1. Rajesh S, Bansal K, Sureka B, et al. The imaging conundrum of hepatic lymphoma revisited. Insights Imaging. 2015;6:679–92. 2. Anthony PP, Sarsfield P, Clarke T. Primary lymphoma of the liver: clinical and pathological features of 10 patients. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43:1007–13. 3. Howell JM, Auer-Grzesiak I, Zhang J, et al. Increasing incidence rates, distribution and histological characteristics of primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a North American population. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:452–6. 4. Chim CS, Choy C, Ooi GC, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;40:667–70. 5. Maher MM, McDermott SR, Fenlon HM, et al. Imaging of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:295– 301. 6. Tomasian A, Sandrasegaran K, Elsayes KM, et al. Hematologic malignancies of the liver: spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 2015;35: 71–86. 7. Abdulqadhr G, Molin D, Aström G, et al. Whole-body diffusionweighted imaging compared with FDG-PET/CT in staging of lymphoma patients. Acta Radiol. 2011;52:173–80. 8. Yoon MA, Lee JM, Kim SH, et al. Primary biliary lymphoma mimicking cholangiocarcinoma: a characteristic feature of discrepant CT and direct cholangiography findings. J Korean Med Sci. 2009; 24:956–9. 9. Abe H, Kamimura K, Kawai H, et al. Diagnostic imaging of hepatic lymphoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:435–42. 10. Ashmore P, Patel M, Vaughan J, et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a case series. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2015;8:78–84. 1. Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7310-5709 2. Grupo Fleury, São Paulo, SP, Brazil; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1911-9090 3. Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil; Diagnósticos da América S/A, Barueri, SP, Brazil; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2019-7918 4. Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6947-1375 5. Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil; Grupo Fleury, São Paulo, SP, Brazil; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2339-5730 6. Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM-Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil; Grupo Fleury, São Paulo, SP, Brazil; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2701-1928 Correspondence: Dr. Aldo Maurici Araújo Alves EPM-Unifesp – Departamento de Diagnóstico por Imagem Rua Napoleão de Barros, 800, Vila Clementino São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 04024-002 Email: aldomaurici@gmail.com Received 31 January 2018 Accepted after revision 3 April 2018 Publication date: 15/08/2019 |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554