Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 47 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2014

Vol. 47 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2014

|

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

|

|

Prediction of early and late preeclampsia by flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery |

|

|

Autho(rs): Augusto Henriques Fulgêncio Brandão1; Aline Aarão Evangelista2; Raphaela Menin Franco Martins2; Henrique Vítor Leite3; Antônio Carlos Vieira Cabral4 |

|

|

Keywords: Preeclampsia; Ultrasonography; Vascular endothelium; Prediction. |

|

|

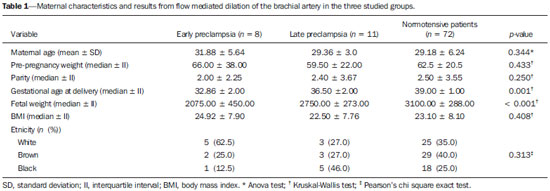

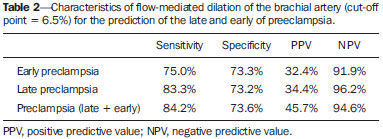

Abstract: INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia (PE) and other hypertensive disorders in pregnancy account for the highest portion of maternal mortality and perinatal morbidity in Brazil, as in most countries around the world. An appropriate prenatal follow-up of pregnant patients considered to be under risk for developing such a disorder is essential in the attempt to reduce mortality/morbidity rates. A satisfactory clinical prediction strategy could allow the early intervention or even therapies aimed at changing the natural course of PE(1–3). The causes for PE are not completely understood, however, accumulated evidences indicate the placenta as the site of origin of the disease. Most recent physiopathological theories indicate that an inflammatory reaction associated with a placental oxidative stress takes systemic proportions, generating endothelial dysfunction in the maternal body. Such an event would be considered the key-point for the development of all clinical manifestations and complications from PE(3–5). By means of biophysical and biochemical methods it is possible to detect the endothelial injury before it generates noticeable symptoms(6,7). As it has already been clinically demonstrated that such an event can be diagnosed before the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of PE are met, tests evaluating the endothelial function could be utilized as PE predictors(8). Contrary to poor placental perfusion, that is the most striking event in the physiopathology of early PE (clinical manifestations before 34 weeks of gestation) as compared with late PE (manifestations after 34 weeks), endothelial dysfunction is present in both PE forms(6–8). Thus, the evaluation of the endothelium function would be clinically interesting to predict any form of PE. Considering the above, the present study was aimed at evaluating the accuracy in the prediction of both early and late PE by means of flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery (FMD). MATERIALS AND METHODS Patients The present study was duly approved by the Committee for Ethics in Research of Hospital das Clínicas – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (HC-UFMG). A total of 91 patients were recruited at the high-risk prenatal service of HC-UFMG for this longitudinal study. The selected patients were duly informed on the study and signed a term of free and informed consent. The demographic characteristics of the studied patients are shown on Table 1, divided into three study groups created according to the pregnancy outcome (development of early PE; development of late PE; normotensive). All the selected patients presented with at least one of the following risk factors for development of PE, according to the study developed by Duckitt et al.(9): chronic arterial hypertension (23; 25.5%); pre-gestational diabetes mellitus (according to criteria defined by the American Diabetes Association in 2011(10)) (16; 17.5%); personal history of PE in previous gestation (21; 23.0%); family history (mother or sister) of PE (16; 17.5%); high body mass index (defined as > 35 kg/m2) (15; 16.5%). Patients presenting with chronic arterial hypertension were those who had been diagnosed as hypertensive before gestation; those presenting with arterial pressure levels > 140 × 90 mmHg before the 20th week of gestation; those who remained hypertensive for at least 12 weeks after delivery. The diagnosis of PE was made according to the criteria defined by the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy, 2000(11). According to such a classification, PE is defined as the increase in arterial pressure levels after 20 weeks of gestation (pressure level > 140 × 90 mmHg in two measurements with an interval of 6 hours), followed by the presence of proteinuria (1+ or more in the measurement of proteinuria with test strips or 24 hour proteinuria > 0.3 g/24 hours). The superposition of PE in patients presenting with chronic hypertension was considered, according to the bulletin of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists(12) modified at the authors' service, as one of the following facts was present: 1) severe arterial pressure increase (higher than 160 × 110 mmHg); 2) massive proteinuria (more than 2.0 g/24 hours); 3) significant increase in arterial pressure levels after a period of good control; 4) serum creatinine levels reaching values above 1.2 mg/dl. After regular prenatal visits between the 24+0 and 27+6 weeks of gestation, the patients were invited to participate in the present study. After their consent, the patients were submitted to the FMD exam. All examinations were performed by a single professional from HC-UFMG, trained and certified in ultrasonography. Flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery Flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery was performed with a Sonoace 8800 (Medison) ultrasonography apparatus with color Doppler and 4–8 MHz linear probe. Previously to the scan, the patients were placed at rest, in dorsal decubitus, for 15 minutes. The measurement of arterial pressure was performed in all patients and the brachial artery was medially identified in the antecubital fossa of the dominant upper limb. An image of the vessel was obtained at approximately 5 cm from the elbow, with a longitudinal section (mode B) during the moment of minimum distension of the vessel, corresponding to the cardiac diastole, with the image being obtained by retrieval by means of the cine loop of the equipment. The image was frozen for obtaining the average of three measurements of the vessel caliber (D1). After this first measurement, the cuff of the sphygmomanometer, distally placed (on the forearm) at the site of measurement of the brachial artery, was inflated for 5 minutes up to a pressure above 250 mmHg, and then it was slowly deflated. The average of three new measurements of the vessel caliber was obtained with the same technique previously described, after one minute from the cuff deflation (D2). The FMD value was obtained by means of the following formula: FMD (%) = [(D2 – D1)/D1] × 100 where: D1 = basal diameter; D2 = post-occlusion diameter. Based on data from a study developed at HC-UFMG(8), a cut-off value of 6.5% was utilized for the FMD results, with any results below such value being considered as altered. Statistical analysis The normality of continuous data was verified by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Student's t test was utilized for comparison of variables with normal distribution among patient groups who developed PE and the group that did not develop PE. The Pearson's chi-square test was utilized for comparison of categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney T test was utilized for comparison of continuous variables without normal distribution. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. The analyses were performed with the aid of the software SPSS®19 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago: USA). For determining a cut-off value for FMD, a value defined in a study developed in the authors' institution was utilized, with a population considered as being at high-risk for developing PE. RESULTS From the total of 91 patients initially recruited, 19 developed PE (eight cases of early PE and 11 cases of late PE). The other 72 patients remained normotensive up to the seventh puerperal day. A statistically significant difference was observed (p < 0.001) in the comparison of the median FMD values between the studied groups. Patients who developed either early or late PE (4.00 ± 6.00 and 3.00 ± 3.00, respectively) presented lower values than those in the group of patients who remained normotensive throughout gestation (9.00 ± 5.00). By utilizing a cut-off point of 6.5%(8), the sensitivity of FMD for the prediction of early PE was 75.0%, with specificity of 73.3%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 32.4%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 91.9%. For the prediction of late PE, sensitivity was 83.3%, specificity value was 73.2%, PPV was 34.4% and NPV was 96.2%. For prediction of all associated forms of PE, sensitivity was 84.2%, specificity was 73.6%, PPV was 45.7% and NPV was 94.6%. The predictive characteristics of FMD are shown on Table 2.  DISCUSSION The identification of pregnant patients at increased risk for PE may determine a more specialized and thorough prenatal follow-up, allowing earlier interventions as necessary, thus preventing and even changing the natural course of PE, and improving maternal and perinatal outcomes related to the condition(13,14). The results demonstrate that altered FMD values precede the typical increase in pressure observed in PE, in any of its clinical presentations. Such a fact not only strengthens the possibility of utilizing FMD as a clinical tool for predicting PE, but also contributes for a better understanding of the disease physiopathology. FMD evaluates the integrity of the endothelium as a paracrine structure responsible for the control of the vascular tone. Decreased FMD values in patients who subsequently develop PE demonstrate a compromising of the endothelial function between the 24th and 28th gestational weeks, much before the clinical diagnosis of the syndrome. Endothelial injury as a physiopathological event of PE has already been demonstrated both in the late and early forms of the disease(15), by biochemical and biophysical methods, particularly FMD. Such a phenomenon precedes the clinical manifestations of the disease, so it is natural to consider the utilization of FMD as a method for predicting the onset of the disease. Savvidou et al. have demonstrated that patients with subsequent development of PE or restricted intrauterine growth presented with decreased FMD values when compared with patients who presented favorable gestational development(16). In 2003, Takase et al., applying FMD in a group of pregnant women at the end of the second gestational trimester, found sensitivity values close to 90%; however, those authors did not differentiate between the two clinical presentations of PE (late and early)(17). Other studies have demonstrated that the FMD values are significantly reduced at the end of the second trimester in pregnant women who later develop either late or early PE(18,19). The association of FMD with Doppler flowmetry of uterine arteries also presented good results in the prediction of PE(20). The present study results demonstrate that the application of FMD in pregnant women considered to be at risk for developing PE is effective in the purpose of identifying those patients with some degree of endothelial involvement and, subsequently, developed the early or late presentations of the disease. Similarly to FMD, Doppler flowmetry of uterine arteries evaluates the placentation process, a phenomenon that is compromised in the physiopathological course of PE. However, failure in the trophoblastic invasion is remarkable only in the early presentation of PE, and consequently, Doppler flowmetry of uterine arteries is an interesting method just for the prediction of the disease before the 34th week, which corresponds to a percentage that varies between 10% and 15% of the total cases of PE(1,2,13). Only patients with risk factors for development of PE were included in the present study. Considering that such patients are those that benefit most from a differentiated follow-up, PE prediction tests should be primarily applied for such patients. However, a subgroup of the recruited patients presented comorbidities known to be connected with endothelial injury, independently from the development of PE. Such a fact may explain the reason why, in all patient groups, the FMD values are lower than those reported in other studies in the literature, which utilized the same described technique. The identification of patients with endothelial dysfunction could allow for the selection of a group of pregnant women that can benefit from the introduction of therapies that protect or recover the injured endothelium with the purpose of preventing, mitigating or even delay the physiopathological process of PE. CONCLUSION FMD, as applied at the end of the second gestational trimester, demonstrated to be an appropriate tool for the prediction of pre-eclampsia, identifying with good accuracy those patients that subsequently developed PE in any of its clinical presentations. REFERENCES 1. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2005 – make every mother and child count. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. 2. Barton JR, Sibai BM. Prediction and prevention of recurrent preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 1):359–72. 3. Magee LA, Helewa M, Moutquin JM, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(3 Suppl):S1–48. 4. Pennington KA, Schlitt JM, Jackson DL, et al. Preeclampsia: multiple approaches for a multifactorial disease. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:9–18. 5. Lyall F, Greer IA. The vascular endothelium in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Rev Reprod. 1996;1:107–16. 6. Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46:1243–9. 7. Young BC, Levine RJ, AnanthKarumanchi S. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2010;5:173–92. 8. Brandão AHF. Avaliação da função endotelial e da perfusão uterina em gestantes com fatores de risco para pré-eclâmpsia. [Tese de doutorado]. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais; 2012. 9. Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2005;330:565. Epub 2005 Mar 2. 10. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 Suppl 1:S11–61. 11. [No authors listed]. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:S1–S22. 12. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins – Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159–67. 13. Plasencia W, Maiz N, Poon L, et al. Uterine artery Doppler at 11 + 0 to 13 + 6 weeks and 21 + 0 to 24 + 6 weeks in the prediction of pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:138–46. 14. Duley L. The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:130–7. 15. Brandão AHF, Barbosa AS, Lopes APBM, et al. Dopplerfluxometria de artérias oftálmicas e avaliação da função endotelial nas formas precoce e tardia da pré-eclâmpsia. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:20–3. 16. Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003;361:1511–7. 17. Takase B, Goto T, Hamabe A, et al. Flow-mediated dilation in brachial artery in the second half of pregnancy and prediction of pre-eclampsia. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:697–704. 18. Brandão AH, Cabral MA, Leite HV, et al. Endothelial function, uterine perfusion and central flow in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;99:931–5. 19. Brandão AH, Pereira LM, Gonçalves AC, et al. Comparative study of endothelial function and uterine artery Doppler velocimetry between pregnant women with or without preeclampsia development. J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:909315. 20. Calixto AC, Brandão AHF, Toledo LL, et al. Predição de préeclâmpsia por meio da dopplerfluxometria das artérias uterinas e da dilatação fluxo-mediada da artéria braquial. Radiol Bras. 2014;47:14–7. 1. PhD, Researcher, Center of Fetal Medicine, Hospital das Clínicas – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil 2. Physicians at the Maternity of Hospital das Clínicas – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil 3. PhD, Associate Professor of Gynecology and Obstetrics, School of Medicine – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil 4. PhD, Full Professor of Gynecology and Obstetrics, School of Medicine – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil Mailing Address: Dr. Augusto Henriques Fulgêncio Brandão Hospital das Clínicas – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Avenida Professor Alfredo Balena, 110, Santa Efigênia Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, 30130-100 E-mail: augustohfbrandao@hotmail.com Received August 25, 2013. Accepted after revision March 10, 2014. Study developed at Hospital das Clínicas – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Financial support: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (Fapemig). |

|

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554