Radiologia Brasileira - Publicação Científica Oficial do Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia

AMB - Associação Médica Brasileira CNA - Comissão Nacional de Acreditação

Vol. 43 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2010

Vol. 43 nº 4 - July / Aug. of 2010

|

EDITORIAL

|

|

Which is your diagnosis? |

|

|

Autho(rs): Marcelo Souto Nacif1; Teresa Cristina de Castro Ramos Sarmet dos Santos2; Justin Huang3; Eliane Lucas4; Christopher T. Sibley5; Alair Augusto Sarmet Moreira Damas dos Santos6 |

|

|

A two-year-old male child was brought with complaints of fatigue and recurrent pneumonia. Chest radiography demonstrated pulmonary congestion and enlarged left heart chambers. Echocardiography confirmed situs solitus and ventriculoarterial and atrioventricular concordance. The left heart chambers were dilated with a double-orifice mitral valve without functional stenosis. An anomalous intraventricular muscle band was seen dividing the ventricle into two cavities. The patient was referred to the Radiology and Imaging Center of Hospital de Clínicas de Niterói for evaluation by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

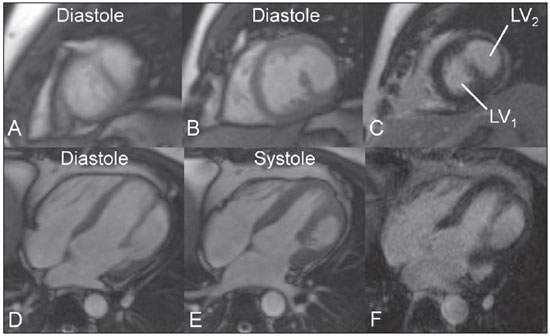

Images description Figure 1. ECG-gated MRI morphology, black-blood, T1-weighted sequence with fat suppression in short axis view, covering the whole extent of the left ventricle from the base to the left ventricular apex at mid-diastole. An abnormal muscle band divides the ventricle into two cavities.  Figure 1. ECG-gated MRI morphology, black-blood, T1- weighted sequence with fat suppression in short axis view, covering the whole extent of the left ventricle from the base to the left ventricular apex at mid-diastole. Figure 2. ECG-gated cine-MRI acquisition in short axis covering the whole extent of the left ventricle from the base to the left ventricular apex during diastole.  Figure 2. ECG-gated cine-MRI acquisition in short axis covering the whole extent of the left ventricle from the base to the left ventricular apex during diastole. Diagnosis: Double-chambered left ventricle. COMMENTS Outpouching of the left ventricle is a rare condition with heterogeneous causes ranging from congenital abnormalities, such as diverticula or muscle bands, to complications secondary to myocardial infarction, such as aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm. Distinguishing amongst these etiologies is challenging but of great clinical importance given the wide range of risks and implications involved(1–3). Double-chambered left ventricle (DCLV) is characterized by the division of the ventricular chamber into two chambers by abnormal muscular tissue. It is best differentiated from left ventricular aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms by the fact that the double-chambered ventricle exhibits contractile motion during systole. Ventricular aneurysm lacks complete layering of the ventricular wall, and thus expands slightly due to the increased pressure during systole(4,5). The differentiation between doublechambered left and right ventricles is clear as they have different pathophysiology. Double-chambered right ventricle (DCRV) is more common and is often presented with murmur and exertional dyspnea. Studies have found that DCRV is associated with septal defects, tetralogy of Fallot, and transposition of great arteries. Conversely, DCLV is commonly asymptomatic. DCRV is often caused by a progressive thickening of the right ventricular septum due to the presence of anomalous muscle bundles. This causes a pressure gradient, and two chambers in series develop. In contrast, the chambers of a DCLV are in parallel and present less of a pressure gradient, as both contract synchronously. The DCLV etiology is less known, but the anomaly is thought to be congenital and non-progressive(6,7). Usually, DCLV is incidentally found in the course of an evaluation for other cardiovascular abnormalities. As this is an extremely rare finding, no definite data regarding the prognosis, outcomes and potential complications, such as risk of embolism, of DCLV are available. It is generally believed that DCLV poses little risk to the patient. Treatment, if any, is usually guided by the presence of other associated abnormalities(8,9). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is useful in the assessment of associated conditions and to better understand the disease. Magnetic resonance imaging can demonstrate changes in the ventricular contractility, presence or absence of fibrosis and is useful in the follow-up of patients with DCLV (Figure 3).  Figure 3. A 29-year-old male patient presented with myocardial infarction signs. Cardiac MRI with the cine (A,B,D,E) and late enhancement (C,F) techniques. A: Cine-MRI, short axis view at the apical portion of left ventricle showing both cavities. B: Cine-MRI, short axis view at the middle portion of left ventricle showing both cavities. C: Delayed enhancement, short axis view at the middle portion of left ventricle without scar/fibrosis. D: Cine-MRI four-chamber view at diastole showing both cavities. E: Cine-MRI, four-chamber view at systole showing the thickening of the lateral wall of the LV2. F: Delayed enhancement, fourchamber view without scar/fibrosis. Illustrative images of a case kindly provided by Drs Ricardo Andrade Fernandes de Mello, Orly de Oliveira Lacerda Junior, and Renato Antunes Machado. Final considerations The authors emphasize the rarity of this congenital anomaly in association with double mitral valve lesion and the diagnostic approach utilizing echocardiography and cardiac MRI. REFERENCES 1. Gerlis LM, Partridge JB, Fiddler GI, et al. Two chambered left ventricle. Three new varieties. Br Heart J. 1981;46:278-84. 2. Vaidiyanathan D, Prabhakar D, Selvam K, et al. Isolated congenital left ventricular diverticulum in adults. Indian Heart J. 2001;53:211-3. 3. Krasemann T, Gehrmann J, Fenge H, et al. Ventricular aneurysm or diverticulum? Clinical differential diagnosis. Pediatr Cardiol. 2001;22: 409-11. 4. Caron KH, Hernandez RJ, Goble M, et al. MR imaging of double chambered left ventricle. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:140-2. 5. Harikrishnan S, Sivasankaran S, Tharakan J. Double chambered left ventricle. Int J Cardiol. 2002;82:59-61. 6. Cil E, Saraçlar M, Ozkutlu S, et al. Double-chambered right ventricle: experience with 52 cases. Int J Cardiol. 1995;50:19-29. 7. Hoffman P, Wójcik AW, Rózanski J, et al. The role of echocardiography in diagnosing double chambered right ventricle in adults. Heart. 2004;90: 789-93. 8. Kay PH, Rigby M, Mulholland HC. Congenital double chambered left ventricle treated by exclusion of accessory chamber. Br Heart J. 1983;49: 195-8. 9. Kumar GR, Vaideswar P, Agrawal N, et al. Double chambered ventricles: a retrospective clinicopathological study. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;23:135-40. |

|

GN1© Copyright 2025 - All rights reserved to Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia e Diagnóstico por Imagem

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554

Av. Paulista, 37 - 7° andar - Conj. 71 - CEP 01311-902 - São Paulo - SP - Brazil - Phone: (11) 3372-4544 - Fax: (11) 3372-4554